The new Princeton Art Museum is a good building, certainly in terms of the spaces that unfold in its almost 150,000 square feet, the qualities of light evident in those stately rooms, and the detailing evident in almost every moment where surfaces meet or our body is invited to touch. Whether it is the right building in its place and for this time is another question.

As a former museum professional and thus recovering museum operations nerd, I was in heaven during my visit to the brand-new museum, which opened last week in the middle of the campus to a design by David Adjaye.

First, there is the fact that it is right in the middle of the campus. It is rare for a university, certainly one as prominent as Princeton, to put their collection not just on, but in the middle of their complex. Usually, such structures are at the edge of the academic zone, if they are there at all.

The Museum had historic dibs on their location, but given academic politics it is either a sign of the power of the donors involved or a particularly enlightened administration that the institution was allowed to not only stay there but build such a large new building on the site.

Adjaye designed the sequence of these skylit halls around a core dedicated to those elements that cannot bathe in natural light, such as the Museum’s extensive Chinese art collection, and densely packed racks of ceramic, statues, and other three-dimensional objects from what, at 117,000 pieces, is one of the largest collections in a university art museum in the United States.

The building develops across no fewer than five main blocks that are offset from each other, so your movement through the collection is on of sidling and sideway glance and diagonals and turns occasioned by the promise of another room unfolding off to your side.

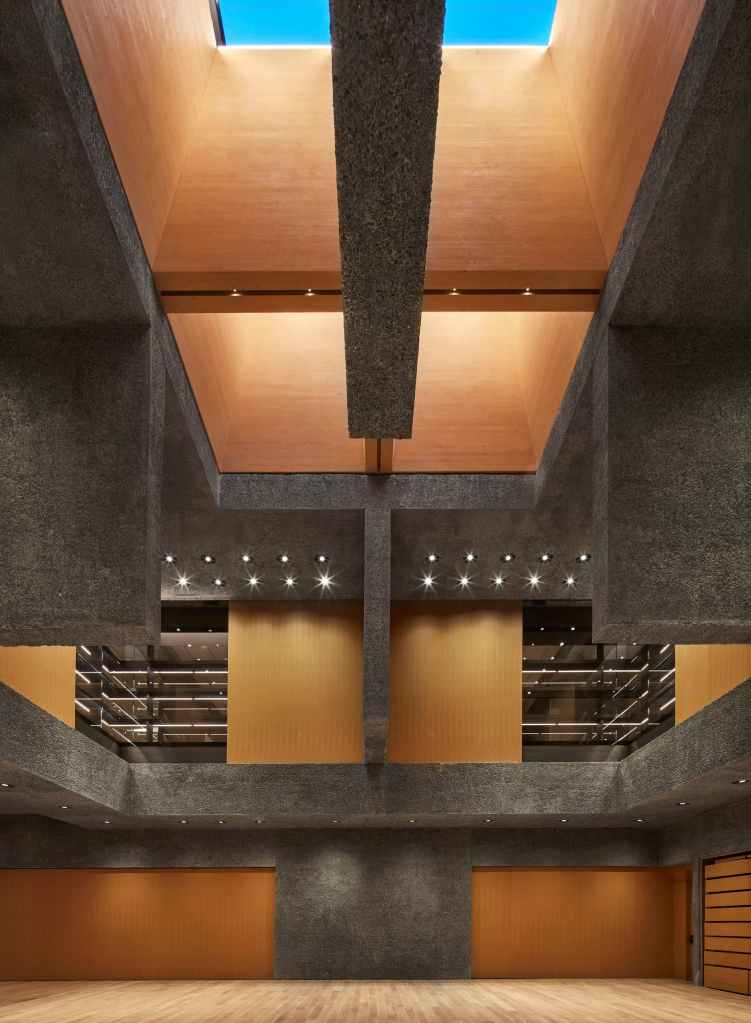

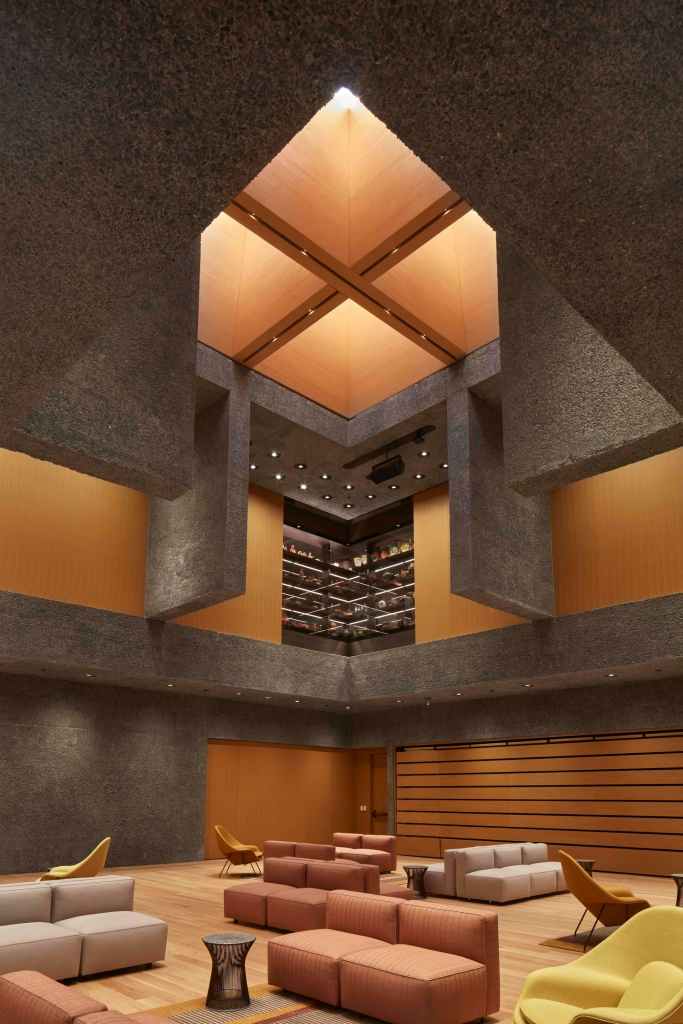

All of this unfolds on the piano nobile Adjaye positioned on top of three intersecting axes leading in from different parts of the campus. Where these corridors come together is the occasion for the requisite grand staircase in its own skylit hall, but there is also a Great Room, where a student was tinkling away on a grand piano during my visit.

It is obviously a place for parties as well as recitals, but it is also what Louis Kahn would have called The Room, a space without definite function that keys in the whole architecture as a framing of the meeting of people and art. Kahn himself produced one of the greatest of these at the British Art Center at Yale University in 1977, and both here and throughout the building you can feel Adjaye, perhaps a little excessively, channeling his inner Kahn.

Tucked away between, around, and on top of these spaces are teaching and conservation labs, education spaces, offices, and an elegant restaurant with a view back over the adjacent quad. Somehow Adjaye managed to even create a huge loading dock with all the proper art handling facilities on this tight site. This Princeton Art Museum certainly has all mod cons and has them of the right kind in all the right places.

Finally, there is the detailing. As an example, Adjaye set the handrail of the grand stair into a hollowed-out section of rough-hewn concrete, creating an updated version of I.M. Pei’s marble original at the East Wing of the Natural Gallery. Wood benches invite you to lean back and look around.

Everywhere one wall meets another, you not only understand the relation between the two planes and how they were made but are invited to explore them by touch as well as sight. This building is as fine as a great deal of money was able to make it –but also as good as the designers were able to produce.

So what is not to like? There is first, an issue extraneous to the architecture’s physical aspects, though some may differ. Adjaye was absent from the public and press openings because of past accusations of sexual harassment and predation against him. I believe that issue has and is being discussed in relationship to authorship in other places.

Though I condemn his actions, I do not believe that we can deny that he was the architect of this building, even if the Museum itself seemed to be trying to sweep him under, if not the carpet, the parquet wood floors.

The whole point of architecture is that, unlike other forms of art, it demands the sublimation of the maker’s personality and intent into the building. In this case, the Museum has done that by pointing out the importance of the design and client team, rather than the heroic designer they posed when the building’s design was first announced.

However, I do think we have to accept that the building is there, and that Adjaye was a major, if not the main author. The only way to truly respond if you believe that Adjaye’s actions (which he has objected to and continues to deny with great vigor) put his work beyond the pale is to ignore the building.

I have not. I both think it is too important and believe that whatever the result of an evaluation of the building in terms of personality flaws or ethical lapses might be, I cannot find any clear relation between its forms, spaces, and materiality and whatever David Adjaye’s character might be.

Sticking to what is there, there is the outside. The building is not only large but feels even bigger. That is partially because of that grand and tall second floor, as well as because of the leisurely alignment of all those rooms that creates such glorious sequences on the inside. The posing of the galleries on walls that slide under them only makes their weight more apparent.

But Adjaye also detailed the blocks as mostly windowless boxes whose scale he tried to manipulate by turning the walls into concrete fins he angled and whose ends he has left rush to let them act as counterpoints to the smooth finishes of the remainder of the material. The effect is, in my opinion, to make the blocks appear even heavier, scaleless, and forbidding.

While Adjaye might have wanted to pick up on the classical and Neo-Romanesque detailing of some of the surrounding buildings in the articulation of some of the façade elements, he instead recalls bunkers and Neo-Brutalist buildings. Unlike is the case in the best of the latter, such as Marcel Breuer’s Whitney Museum, which he also references throughout the Art Museum, there is not expression or sculptural presence, only the weight of these inward-turned masses imposing themselves on scene of varied, but all both humanly and institutionally scaled, structures.

As an outsider looking at the building, part of me wonders what they were thinking. They knew the building was huge by its nature; could they not have sunk part of it in the ground? Could they have tucked some of them in a hidden third and fourth floor masked by the lower parts of the Museum?

Better yet, could they not have left the galleries and teaching spaces on the main campus and, whatever the cost and complications in logistics, moved the other functions to a nearby site? However, that is, as I say, the perspective of a Monday quarterback and somebody not trying to optimize the building’s operations and importance.

Finally, there is the question of the style or mode of architecture the Princeton Art Museum presents with such clarity and completion. This is a profoundly conservative building in the way it shows art. The modes of displays and the spaces themselves could have been designed in a similar manner fifty years ago, and versions of them were.

The fact that the tradition was carried on with skill only makes that lack of innovation clearer. The very notion of making such a grand structure, including elements such as the great stair and room and the placing of the honorific functions on that “noble floor” further a very set notion of what an art museum is, how it functions, and for whom. By making it so big and bold, Adjaye and his collaborators and clients have only furthered all those old ways of doing things.

If you believe that is the right thing to do, and if you believe that art, increasingly undervalued in our society and especially in our educational system, could use a big boost, then this is a building for you. If you want to experience good art in a beautiful setting, this is a new art Mecca.

If you have questions about any of those notions, about the leeway we give architects in so many ways, or about the bravura confidence built into both institutional logic that produces such buildings and the modern architecture that serves it, go someplace else.

The views and conclusions from this author are not necessarily those of ARCHITECT magazine.

Read more: The latest from columnist Aaron Betsky includes reviews of: Victor Legorreta | Mexico City Underwater | On Vitruvius | On Olive Development | Calder Gardens | White House and Classical Architecture | Louis Kahn’s Esherick House | Ma Yansong’s Fenix Museum | The Cult of Emptiness | An Icon in Waiting | Osaka Expo | Teamlab | the Venice Biennale of Architecture | On Michael Graves | On Censorship or Caution? | Uniformity in Architecture | Book on Frank Israel | Legacy of Ric Scofidio| Fredrik Jonsson and Liam Young | DSR’s New Book | the Stupinigi Palace | Living in a Diagram | Bruce Goff | Biopartners 5 |Handshake Urbanism | the MONA | Elon Musk’s Space X | AMAA | DIGSAU | Art Biennales | B+ | William Morris’s Red House | Dhaka | Marlon Blackwell’s new mixed-use development | Eric Höweler’s social media posts,| Peter Braithwaite’s architecture in Nova Scotia,| Powerhouse Arts, | the Mercer Museum, | and MoMA’s Ed Ruscha exhibition.

Keep the conversation going—sign up to our newsletter for exclusive content and updates. Sign up for free.