Architecture of almost every type has become so standardized that designers have even less freedom to make new spaces or surprise with form than the little room they had before. In the museum type, design means creating an entrance as spectacular as possible, almost always with a central staircase carried out with some bravura; surrounding that signature statement with a large open space that can be rented out for events; and then make galleries that are as sparse, simple, and divisible as possible. If you are going to follow that mandate, then I would hope you could it as well as Ma Yansong has done at Fenix, the new art museum about immigration in Rotterdam.

Fenix was the name of a warehouse owned by the Holland America Line, one of the largest shipping (both for passengers and goods) companies operating between Europe and the United States throughout the end of the 19th and the first half of the 20th century. The company eventually became a cruise line and was then sold, leaving the majority owners, the van der Vorm family, with a considerable fortune. Of that they put a rumored six hundred million Euro or so into a foundation, Droom en Daad (Dream and Deed) to support the social and cultural life of Rotterdam. They then made Wim Pijbes, the former Director of both the OMA-designed Kunsthal in that city and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, in charge.

The choice was, in my opinion, an excellent one, as few people understand the relationship between art, social work, and audiences better than Pijbes. He has done a great deal of good in the city through grants to existing and new institutions and initiatives (pledging eighty million Euro to Mecanoo’s renovation of the Boymans van Beuningen Art Museum), but he also felt the foundation needed a center. Working with his team, he developed the idea of a museum about what had been the HAL’s focus, immigration, drawn forward into the 21st century. Although there are quite a few institutions devoted to that topic, Pijbes then hit on making this an art, rather than a historical, institute. The Foundation and museum Director Anne Kremers in quick order built up a small, but high-quality collection of both contemporary and historical works that reveal, comment on, or otherwise shine a critical eye on migration, immigration, exile, and collective homelessness.

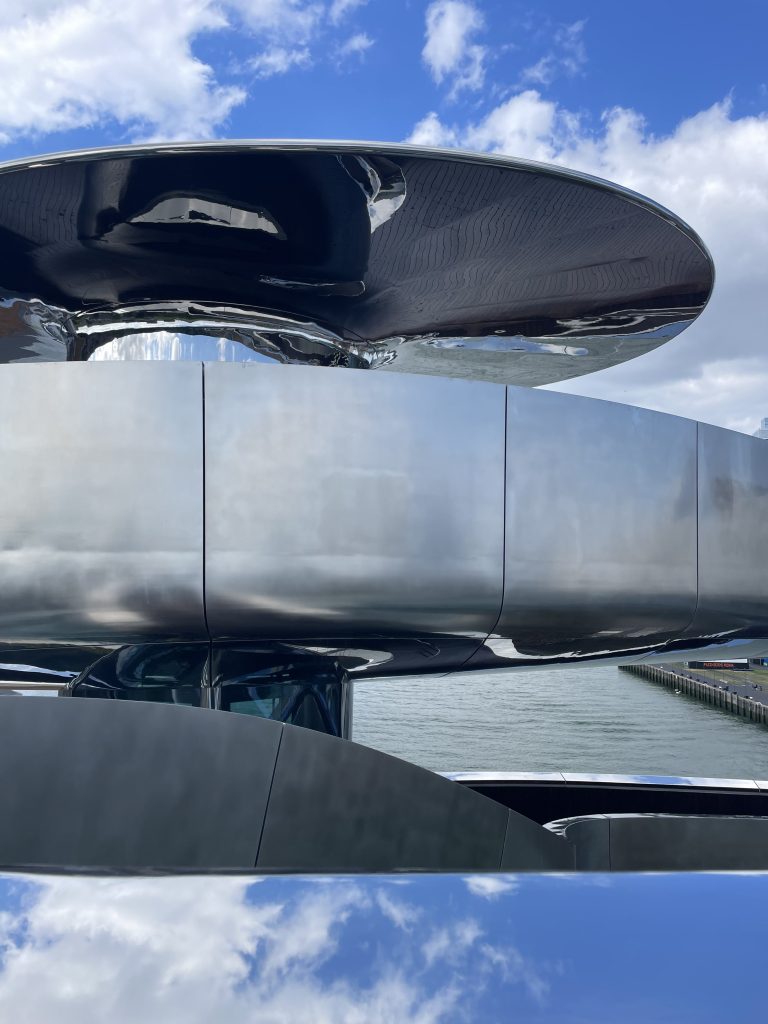

Fenix then hired Ma, who also designed the soon-to-be-completed Lucas Museum in Los Angeles, to transform the warehouse into a home for both this museum and an as-yet not finished performance center adjacent to the now open exhibition space. In response, the architect indeed made the grand central staircase. It is a flash of stainless, polished steel rising out of the middle of the concrete-framed building into a double helix that comes together only at the top, where it forms an observation point from which you can view Rotterdam’s center.

The museum calls the staircase a “tornado,” and the gleaming object certainly has the energy and expressiveness of that weather phenomenon. It also calls to mind the grand staircases that lead cultural elites up the center of such grand institutions as Garnier’s Paris Opera House of 1875. The stair is finally also a metaphor for the movement of peoples in an often violent and fluid (i.e., over the seas) manner. Whatever it means, it is beautiful, a seductive nest of snakes made of continuous curves wrapping around itself and shooting up through and above the building from an open public space outfitted, as is standard operating procedure in museums these days, with restaurant, shop, and catering opportunities.

Ma was able to enhance the tornado’s wow factor because, with a generous budget, he could make the object out of high quality steel formed by CIG Architecture, experts in the realizing art and design objects based on digital data. The detailing is impeccable, although at the top part of the vortex the geometry of the forces of the curves pulls the different pieces far enough apart that you can see the interior structure. Clad on the inside with a dark wood sourced in Norway, the central circulation object is a joy to view from afar or close by, and then to ascend or descend.

Beyond that, there is almost nothing there, but in a good way. The rest of the public spaces, including over twelve thousand square feet of exhibition area on two levels, are empty of any visible design interventions. The concrete has been cleaned and revealed, the windows and skylights remade, and hardware to provide comfort, security, and lighting added with a the most minimal touch possible. In these wide-open spaces, the art objects stand or hang with enough room around them to permit their full enjoyment.

The most spectacular object is the “suitcase labyrinth” of stacked valises, trunks, and roll-ons donated after an open call the museum sent out. With their stickers indicating where they came from or went to, their dings and scratches, and their worn handles, the suitcases come together to surround you with the memory of travel and all the dislocation that act, whether voluntary or forced, entails.

What sets the Fenix aside from other recent art institutions is thus not its design or contents, but the skill with which it has been realized. With enough money to pursue both Dream and Deed, Ma, Kremers, Pijbes, and their team have been able to create a spectacle that, in the first few months since its opening, has already drawn over a hundred thousand people to the fast-gentrifying neighborhood of Katendrecht in Rotterdam’s former harbor. The collection tells the stories of the dis- and relocated with all the power art can muster and a good display of the objects and images demand. The tornado is the anchor, Olympic flame, and symbol of the institution, and has become another signature in a city that already has such spectacular objects as Ben van Berkel’s Erasmus Bridge, the Kunsthal, and MVRDV’s Open Depot.

As Fenix matures, I hope the attraction will hold and the collection will grow with the intelligence it embodies so far. Part of me, however, wishes that for once, with all that money, latitude, and design and art intelligence, it would have been possible to find something to lift us out of the clichés of contemporary art museums.

The views and conclusions from this author are not necessarily those of ARCHITECT magazine.

Read more: The latest from columnist Aaron Betsky includes reviews of: The Cult of Emptiness | An Icon in Waiting | Osaka Expo | Teamlab | the Venice Biennale of Architecture | On Michael Graves | On Censorship or Caution? | Uniformity in Architecture | Book on Frank Israel | Legacy of Ric Scofidio| Fredrik Jonsson and Liam Young | DSR’s New Book | the Stupinigi Palace | Living in a Diagram | Bruce Goff | Biopartners 5 |Handshake Urbanism | the MONA | Elon Musk’s Space X | AMAA | DIGSAU | Art Biennales | B+ | William Morris’s Red House | Dhaka | Marlon Blackwell’s new mixed-use development | Eric Höweler’s social media posts,| Peter Braithwaite’s architecture in Nova Scotia,| Powerhouse Arts, | the Mercer Museum, | and MoMA’s Ed Ruscha exhibition.

Keep the conversation going—sign up to our newsletter for exclusive content and updates. Sign up for free.