Vitruvius, the architect to Augustus Caesar, wrote his treatise on architecture a few decades before the Christian era. It was preserved in Charlemagne’s library, “rediscovered” in 1416, and since then has become the foundational text for the discipline, embedding the orders, geometry, proportion, and other organizing principles into the bones of buildings. What it was when it was written and never has been is a neutral text.

We have long known that Vitruvius wrote it in the service of Rome’s imperial power’s efforts to establish itself in facts on the (urban) ground and defend itself through the tricks and tools the author proposed. We also know that these ten books thus aligned architecture with the notion that the act of building is an assertion of control over reality and human beings by a centralized and male governing force.

From Imperial Rome to Renaissance Italy

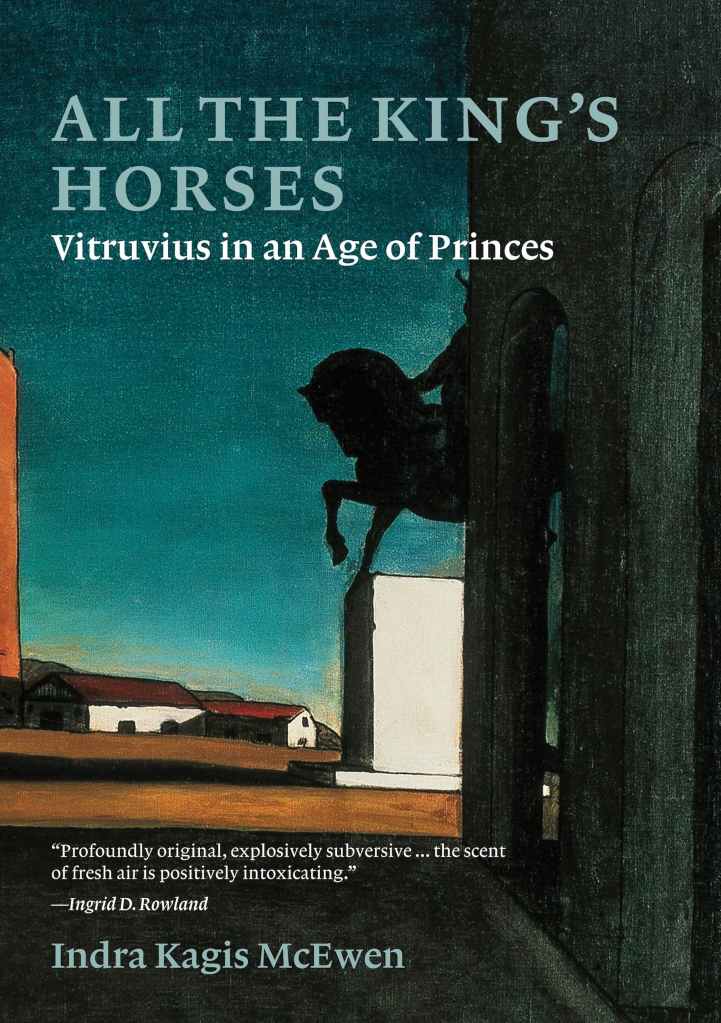

Now comes a book by the scholar Indra Kagis McEwen, All the King’s Horses: Vitruvius in an Age of Princes, to show us how Vitruvius’ text worked in that manner at one particular moment and place.

McEwen argues that Alberti and others in the 15th and 16th century read, translated, and interpreted Vitruvius as part of their own efforts to aid the takeover of Italian cities by popes, dynastic families and warlords.

They did so both by justifying these potentates’ actions in transforming cities into the sites and backgrounds for their palaces, fortresses, militarized public spaces and statues of themselves on horseback, and by helping them to do so in efficient and beautiful ways.

Virtue, Virtus, and the Transformation of the City

At the beginning of this period, in 1339, the artists Lorenzetti in Siena produced the paintings on the subject of “The Good City” that have become a standard for architecture history slide show.

As McEwen points out, Lorenzetti felt the city embodied virtue, or rather its Latin version, virtu: “… just as virtues of all kinds, and a single virtus, contribute to good government in this brilliantly imagined scene, so does the city brought into being by the multiple virtues of many different trades and crafts.” Crucially, McEwen goes on to say (perhaps a bit rashly), “Nobody in Italy was reading Vitruvius yet.”

Fixing Beauty: Perfection as Political Control

As that changed, architects went from finding beauty in the craft and complexity of the urban scene to proposing new qualities of form, space, and geometry as absolutes that architects, working in the service of virtuous overlords, could impose on that urban life forever: “[Their] defining criteria –perfection, coherence, and inviolability—remain[ed] the same.

It was the apparent inviolability of such perfection, its daunting power to intimidate, that made beauty a weapon of choice among the Renaissance princes for whom Alberti wrote. Fixity made it invulnerable and, in theory, impervious to change.”

City as Stage: Case Studies in Urban Reprogramming

In a set of case studies, the author shows how Mantua, Urbino, and other Italian cities were beautified by conditieri, who did so as part of their own transformation from medieval warriors roaming around the country in the search for jobs, wealth, and power, into dynastic overlords who replaced communes with central power they and their dynasty was meant to hold forever.

Hence the erection of the ducal palace of Urbino, lording it over the city and complete with its famous studiolo where the Duke Federico da Moltefeltro surrounded himself with images of his wealth, power, and knowledge. McEwen also cites the church of Sant’Andrea in Mantua, in which Alberti appropriated for the first time the Roman triumphal arch, through which the victorious general marched, into the entrance of the ruling Gonzagas’ family church.

Pienza and the Rise of the Ideal City

In some cases, whole new cities served to spread the lord’s power. This was true for the fortress towns that began to dot the Po valley during this period, but also especially of the town of Pienza, where Pope Pius II, employing the architect Bernardo Rossellino, replaced his native village with a set of public buildings tuned to processionals and other displays of power.

Rome Reordered: The Campidoglio as Propaganda

In Rome, McEwen shows how the Campidoglio is not just a beautiful public plaza finally tuned to perfection by Michelangelo, but how it was part of a campaign by the Popes to control their fief: “The communal government the papacy supplanted had been experimental, disorderly, at times chaotic, and eminently flexible.

From the early fifteen century the popes, as lords of the city, sought to bring this ‘wayward multitude’ –the Roman popolo—under its control. The perfect symmetry of the Campidoglio was lasting proof of their success.”

The Renaissance Mirror: Beauty, Power, and Erasure

The result was a radical transformation of Italy that was part and part of the success of what we think of as the Renaissance. Centralized and rationalized power became mirrored in the arts and realized in three-dimensional space. We think of that as a triumph of beauty and good architecture, exactly as both Vitruvius and readers such as Alberti had hoped, but McEwen bids us remember the costs: “Standing in the way of successful regime change were the communes whose erasure it required.

Erasure not only of their well-established politics but erasure, quite literally, of the places that were the very condition of self-government and tis ruling principle of the common good which took concrete shape in the measurable reality of a shared public realm. Refiguring these places as proof of one-man rule was where architecture, most notably [as proposed by? sic] Vitruvius and his impeccable imperial credentials, came in to create the ‘ideal’ cities, so called, that left little or no surviving evidence of the real ones they displaced.”

A Masculine Aesthetic: Alberti and the Erasure of Craft

Such statements go beyond some of the proofs the author provides, but perhaps that is because of the relatively brief and argumentative nature of this volume. The avenues McEwen suggests could be proven (or disproven) by more careful case studies in other Renaissance Italian cities.

Another virtue of All the King’s Horses is that McEwen ties these realizations of power in space to other aspects of architecture’s character Vitruvius and his interpreters provided, but which is too often overlooked. She notes that in his translation Alberti selected the masculine version of beauty, dignitas, over its feminine counterpart, venustas.

He also claimed virtue for the architect, while for Vitruvius the designer possessed sollertia, which is to say skill or craft, which he used to make buildings that embodied the same virtue as the lords and only they could possess.

Statues, Horses, and the Architecture of Authority

Finally, she argues that Alberti preferred not the “Vitruvian man” as architecture’s organizing figure, but rather “the body of animans , a living creature –paradigmatically the horse—as the embodiment of the harmonious correspondences that conferred on a work of architecture the character of what he called concinnitas and with it the beauty of an ideally unassailable whole.”

Hence the important place statues of the rulers on horsebacks, including the appropriated one of Marcus Aurelius that graces the Campidoglio, in Renaissance squares. And, as the icing on the sexist, militaristic cake, she goes at pains to show how often Alberti, a bit of a self-made man himself, hated what he called the “baseborn masses and the hubbub of working men.”

Seeing Through the Stone

All of this will make you look at such beautiful spaces as the Campidoglio and the palaces and squares the Gonzagas carved out of Mantua with more skeptical eyes. Whether our observations, so shaped by the more than five centuries of using these Renaissance examples of architecture as our own reference points and standards, and thus ready to see only a neutral beauty there, will ultimately really escape from what we now known of those standards of virtue and rightness remains to be seen.

The views and conclusions from this author are not necessarily those of ARCHITECT magazine.

Read more: The latest from columnist Aaron Betsky includes reviews of: On Olive Development | Calder Gardens | White House and Classical Architecture | Louis Kahn’s Esherick House | Ma Yansong’s Fenix Museum | The Cult of Emptiness | An Icon in Waiting | Osaka Expo | Teamlab | the Venice Biennale of Architecture | On Michael Graves | On Censorship or Caution? | Uniformity in Architecture | Book on Frank Israel | Legacy of Ric Scofidio| Fredrik Jonsson and Liam Young | DSR’s New Book | the Stupinigi Palace | Living in a Diagram | Bruce Goff | Biopartners 5 |Handshake Urbanism | the MONA | Elon Musk’s Space X | AMAA | DIGSAU | Art Biennales | B+ | William Morris’s Red House | Dhaka | Marlon Blackwell’s new mixed-use development | Eric Höweler’s social media posts,| Peter Braithwaite’s architecture in Nova Scotia,| Powerhouse Arts, | the Mercer Museum, | and MoMA’s Ed Ruscha exhibition.

Keep the conversation going—sign up to our newsletter for exclusive content and updates. Sign up for free.