Jason Fulford

Construction began in 1933. It was an incredibly ambitious task: The bridge was to be built on the primary spot in California where saltwater and freshwater met, the huge outrush of something like half of all of the state’s freshwater sources to the sea, with tremendous currents and narrow spaces to work in, along with terrible weather, wind and fog and constant moisture everywhere. Just 10 years before the bridge was first being considered, San Francisco had burned to the ground in the Great Earthquake; as they prepared to build the bridge, at enormous cost, the 1929 stock market crash occurred and the Great Depression began. The boldness of the idea in the face of such tremendous forces—the earth opening and cracking, the economy falling and flopping—is astounding. Still, with Strauss’ political finesse, they managed to push it through.

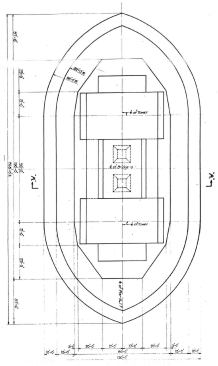

It took an excavation of more than 3 million cubic feet of dirt to make room for the bridge’s anchorages, massive blasting of underwater rock for setting the piles; a 1,100-foot trestle, built out from the south shore, was knocked out first by a ship in the fog and then by a storm. Strauss was assiduous about safety: He was the first engineer to require all workers on a site to wear hard hats, and he built a $130,000 safety net around the bridge to catch any falling workers. (Nineteen were saved who would have faced certain death without the netting. They called themselves the Halfway-to-Hell Club.) There were accidents—10 men died when a platform on the underside of the roadway collapsed—but on the whole the safety record was surprisingly good for such treacherous conditions on such a huge project.

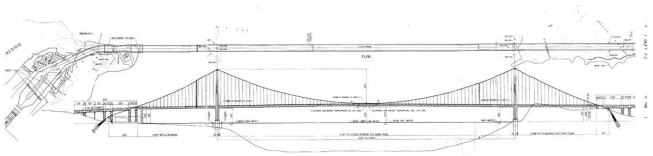

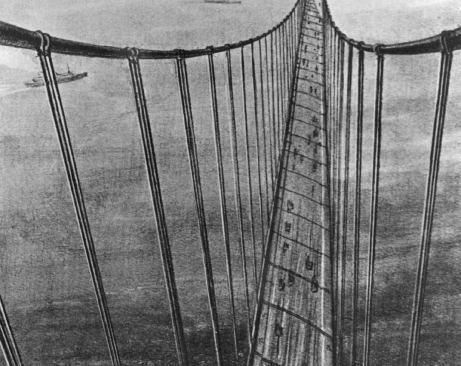

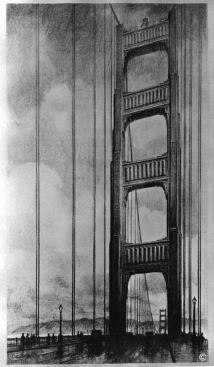

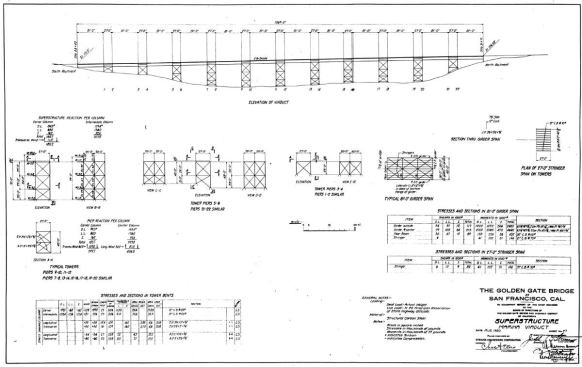

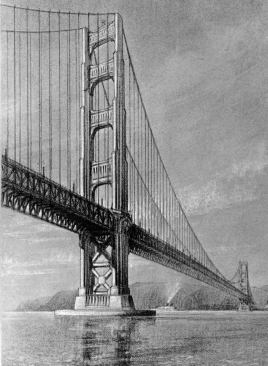

The result, which came to completion in 1937, was the largest suspension bridge in the world, with the tallest bridge towers ever built: 8,981 feet long, with a center span of 4,200 feet, 220 feet above the water at the center and reaching 746 feet into the air. The Oakland Bay Bridge, which had been completed the year before, had been the longest suspended-deck bridge and the longest cantilever bridge in the world, but its main span only stretched about 2,300 feet; the span of the George Washington Bridge, finished in 1931, was 3,500 feet. The San Francisco Chronicle called the new bridge a “$35 million steel harp.”

Its eminently recognizable color—known as “international orange”—came out of an accident. “When they went to construction, they hadn’t decided on the color,” Mulligan said. “The Navy wanted yellow and black, with diagonal stripes on the towers, but when the steel came out it was primed with a reddish-orange color.”

It was a consulting architect, Irving Morrow, who recognized how well it worked. “And he saw that it happened to blend, to blend with the red rock of Marin,” added Mary Currie, the bridge district spokesperson, “and how well it blends when you look back on the city with the sun on it.”

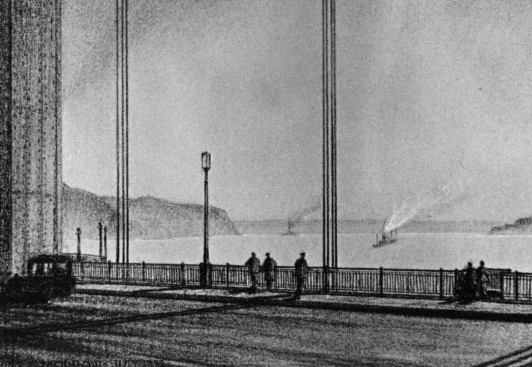

On the first day the bridge opened, 200,000 people crowded onto it and looked back on the city, up to the north, and out to the ocean.

I’D ARRIVED in San Francisco the week after the I-35W bridge in Minnesota had collapsed, and the pack of journalists looking professionally alarmed on television was in high gear. (What other old bridges were moments away from falling? What craven engineers and bureaucrats would they get to blame? And so on.)

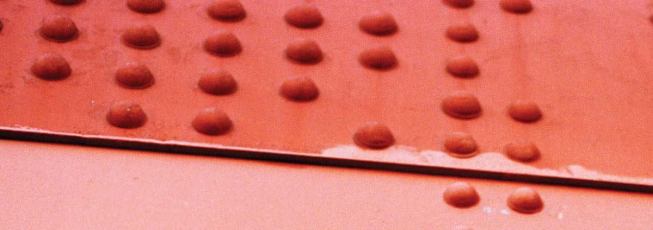

“We inspect every other year,” Mulligan told me. “With a primarily steel structure, there’s a host of issues—but it’s not a welded structure, so we don’t have fatigue cracks at welded connections. We don’t have fatigue issues.”

The issues they do have, he said, include localized corrosion. “It is a marine environment,” he said. “The fog comes in and out a few times a day, so it can be dripping wet all through the summer. And there’s a high salt content to the fog. But we have, what, three dozen painters and a dozen ironworkers who work full time on maintenance for the bridge. And that’s separate from capital projects.”

And the bridge, Currie points out, has a strong history of aggressive capital projects. The famous collapse of the suspension Tacoma Narrows Bridge (designed by Moisseiff) in 1940, three years after the Golden Gate was finished, led engineers to re-evaluate the Golden Gate’s load capacity and ability to withstand high winds; a lower lateral bracing system was put in in the early 1950s. A major inspection about three decades into the bridge’s life resulted in replacement of the suspension cables and rivets in the 1970s and an entirely new roadway deck in the 1980s.