Jason Fulford

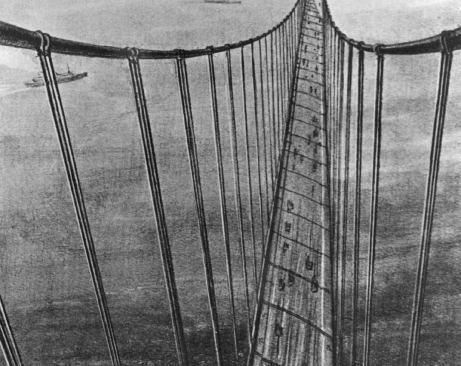

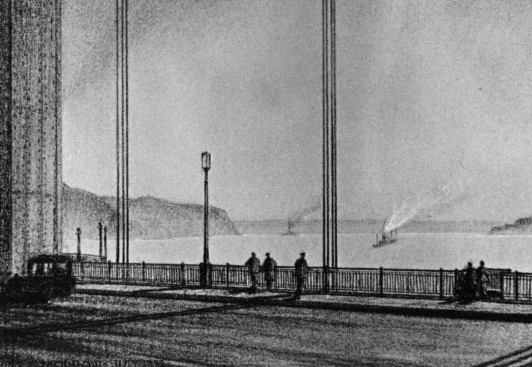

THE BRIDGING OF THE GOLDEN GATE was spurred by the need for an easier commute. By the 1920s, 50,000 commuters a week were coming into the city on ferries, and the number was only increasing. But San Francisco itself, surrounded on three sides by water, had stopped developing after decades of tremendously rapid growth, with no land to expand into, and its future was dependent on access.

As Kevin Starr, the longtime California state librarian and now librarian emeritus, has put it: “San Franciscans were beginning to realize that there was a vast northern and interior empire that had to be integrated into the San Francisco economy and transportation and travel network for San Francisco truly to survive.”

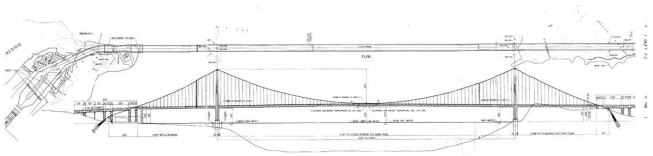

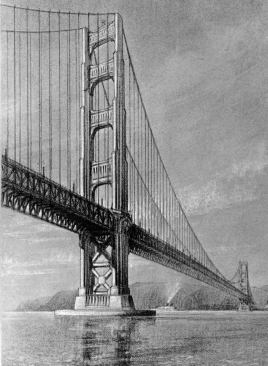

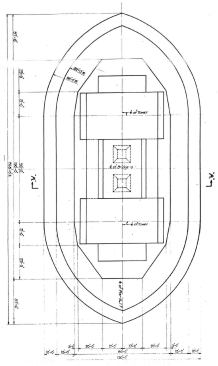

Thus, as early as 1916, the San Francisco city engineer, Michael O’Shaughnessy, began to consult engineers about the possibility of bridging the strait. The typical estimate he received came in at around $100 million, or about $2 billion today, but Joseph Strauss, a Chicago engineer with experience in much smaller projects—his patented design for a bascule bridge, or drawbridge, was used worldwide—proposed to create a bulky cantilever-suspension hybrid for $25 million to $30 million; indeed, his initial cost estimate turned out to be $17 million. (The eventual cost was somewhere between $27 million and $36 million.)

Strauss spent the following years working to raise the money and the support necessary for the bridge, promoting the idea to every community in Northern California that would listen to him. In 1921, he hired Charles Ellis, an academic and engineer, to run the staff of his company and oversee the project, and in 1923 representatives of 21 Northern California counties met to come to an agreement to form the Association of Bridging the Gate, which would become a special district of the state in that same year, created in order to raise money to fund the bridge, largely financed by bridge bonds. The district was officially formed in 1928, with six counties ultimately joining, and in 1930 they voted in a $35 million bond issue, pledging the value of their property and assets against the bridge. The bridge, thus, would not belong solely to San Francisco but to a set of Californian communities, existing as its own entity.

“In the midst of the Great Depression—what a tremendous leap of faith!” Mulligan said, sitting in a conference room in the district offices, which are located yards away from the toll booths at the base of the city side of the bridge. “Because voting in—voting in meant they bet the farm. Literally. They put up their homes, farms, factories as guarantees for the bonds. So the vote meant for 30 years afterward this obligation was mentioned in your deed. Nobody thought it could sustain itself. But it did.”

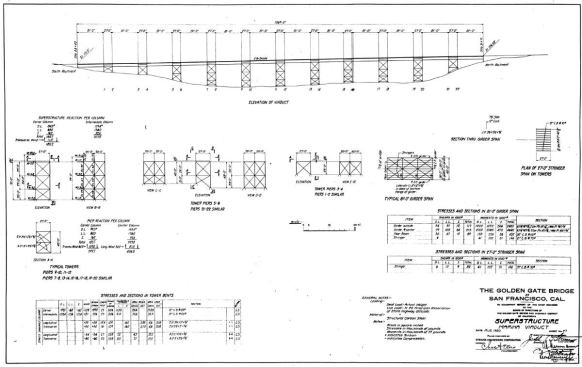

Strauss, born in Cincinnati to an artistic German Jewish family, had founded the Strauss Bascule Bridge Co. in 1902; Ellis, after earning degrees in mathematics and Greek, had started his engineering career at the American Bridge Co. and gone on to teach engineering at the University of Michigan and then the University of Illinois before teaming up with Strauss. They were joined by a host of consultants, including Irving Morrow, a San Francisco architect, and Leon Moisseiff, the Latvian-born designer of New York’s Manhattan Bridge. Moisseiff, who was then in the midst of work on the George Washington Bridge, a suspension design, suggested changing the Golden Gate to an all-wire, stiffened suspension bridge, and after a period of resistance, Strauss agreed to change the design and asked Ellis to draw up plans.

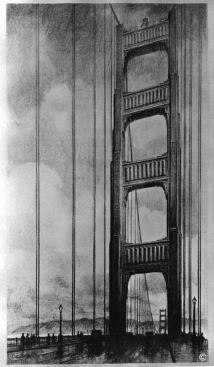

Strauss has ever since been known as the father of the Golden Gate—there is a statue of him at the base of it, with a plaque naming him “The Man Who Built the Bridge.” According to a host of historians today, however, while Strauss sold the idea—and most are quick to emphasize that Strauss was indeed the visionary behind the push for the span, its great champion and its human face—Ellis deserves much more credit than Strauss for the design.

“The bridge belongs to Ellis more than anyone else,” I was told by John van der Zee, whose 1986 history of the bridge, The Gate, led to a re-evaluation of where credit should go. According to Kevin Starr, “Joseph Strauss was not much of an engineer. He was a great visionary. And his initial draft of the Golden Gate Bridge was awkward and clumsy, and if by any impossible chance it had been built, it would have been a catastrophe today.” But after all of Ellis’ work, Strauss fired his deputy in December 1931—no record of his reasons has been uncovered—and Ellis was all but erased from the record until historians like van der Zee drew attention back to him.

In fact, while researching his revisionist history, van der Zee uncovered documents and letters proving the extent to which Ellis’ technical and theoretical work was responsible for the bridge’s ultimate design. That it should have taken so long for Ellis to be recognized is a little baffling—although Ellis was listed merely as Strauss’ chief assistant in Strauss’ 1937 “Report of the Chief Engineer,” it was plain to see Ellis’ signature as the preparer of every drawing—but perhaps the narrative of the Father of the Bridge had simply become too entrenched.