Jason Fulford

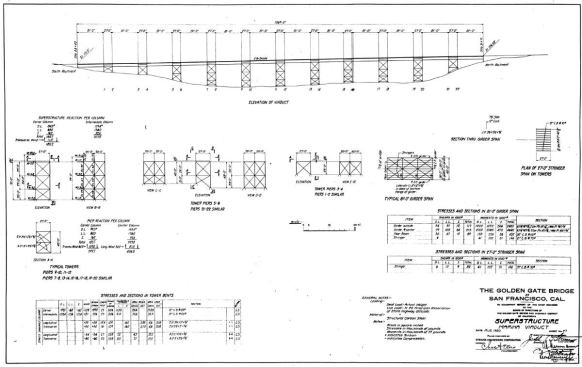

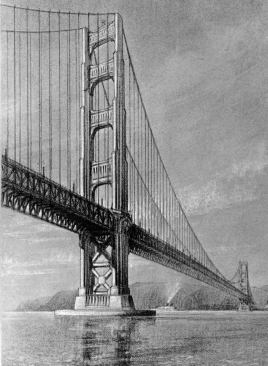

Seismic studies have been essential, of course. “We had to replace the lower lateral bracing for earthquakes,” Mulligan said, showing me photographs of the work as it progressed. Another measure was to reinforce the 250-foot concrete pylons that frame the Fort Point Arch, on the bridge’s south side, with steel plating—nearly 6 million pounds of it. “Concrete is strong if you push, but weak if you pull. And an earthquake pulls. So we added steel, by chipping off 2 inches of the outer concrete, and putting steel plating on it all the way up.” To match the original appearance, they added another 4 inches of concrete on the outside, mimicking the forms of the old lumber impressions in it.

All this work, obviously, costs, and the bridge’s finances have suffered of late. The district’s major source of revenue is tolls—$5 coming into the city, free in the Marin direction—which, in 2006, brought in almost $85 million (the buses and ferries it operates brought in an addition $23 million or so). But the district still faces a budget shortfall of $80 million over the next five years.

With that in mind, the district announced this spring that it would be looking into “corporate partnership” opportunities. While Currie says there will be no naming rights, no neon signs or banners, nothing to disturb the bridge’s aesthetics or identity, the idea stirred up immediate protest. San Francisco Supervisor Jake McGoldrick, who is one of the bridge district’s directors (there are 19 of them, representing the six counties that make up the district authority), told local media, “I think you might as well turn the cathedrals and synagogues into advertising opportunities.”

The other controversy is the idea of a suicide barrier. It is estimated that more than 1,300 people have jumped off the bridge in the 70 years of its existence, and it has long been called a suicide magnet. (A study this spring, however, disproved the myth that people come from all over the world to kill themselves here: 85 percent of jumpers came from the Bay Area, it found, and 92 percent from Northern California.)

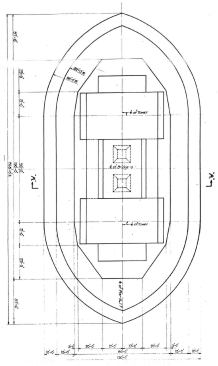

While critics and proponents of a suicide barrier—among the latter are many bereaved family members of jumpers—debated the issue, last year the district began a $2 million engineering and environmental study and, this past August, began looking at three basic concepts: adding to the existing railing to increase its height; nets that extend out horizontally; or an all new vertical barrier or railing system. Wind testing, for speeds up to 100 mph, was successfully completed this spring, and preliminary engineering and environmental studies continue. But any decision will be made by the 19 directors, and it’s a safe bet to say no one really knows how the vote will go.

IF THE MEANING of the Golden Gate Bridge were no more than its role as a conduit between a city and its neighbors, then as those places change, surely the bridge must change the same way. The Bay Area still has progressive tendencies, from gay and lesbian rights to immigrant rights, from literate junkies in the Tenderloin to organic food stores in Berkeley. The region might still be at certain vanguards, of the environmental movement, say, or new technology, but think of this: Marin County is the wealthiest county in the United States. San Francisco is the second wealthiest city in the country, and San Jose, just 50 miles south of it, is the wealthiest. The site of revolution has become the seat of capitalism.

Yet I refuse to accept that the Golden Gate Bridge means only silver Land Rovers. Most of the people I talked to said that the bridge meant very personal things to them. George Sumner is a Bay Area artist who was commissioned to create the official painting of the Statue of Liberty for its 100th anniversary in 1986 and then, in 1987, commissioned to do the official painting of the Golden Gate Bridge on its 50th anniversary.

“My father walked over the bridge when it was built,” he told me. “I was born in 1940, so I wasn’t around yet. But 50 years later, on the anniversary, he came back to do it again. I started from the Marin side and he started from the city side and we met in the middle.”

What surprised me about the suicides was the fact that the majority of jumpers apparently choose to jump facing the Bay side, looking at the city. They jump back toward the thing they’re leaving, back toward the technological just as they prepare to enter the infinite. The reputation of the bridge as the premier destination for suicides points toward it as a representation of a last exit, the place where the country ends and empties out into the sea, with the bridge as its final gate. But yet they jump backwards, into a beginning, out off the end.

Dan Halpern has written for The New Yorker, Rolling Stone, and other publications.