Art Streiber

Sir Fraser Morrison (left) and Peter Morrison

But the firm still had no presence in the United States. Meanwhile, in Princeton, N.J., Bob Hillier was phasing out a long career at the helm of his eponymous firm and on the lookout for a merger opportunity. Engineering companies were coming up with good offers: “But the problem is that architects don’t want to work for an engineering company,” Hillier says. Then an investment banker called him, he remembers, and said, “ ‘I may have a firm that could be interested in you.’ And that was RMJM.”

Next Hillier got a call from Peter Morrison, who made an offer for the firm. It was too low. Morrison called back and upped it; Hillier again declined and suggested that “we ought to close this whole conversation down.” So Morrison immediately got on a plane to New York.

Hillier describes the couple of days that followed as if they were an elaborate parlor game: “I took him to our house for dinner, with a few of the principals. The next morning, he upped his offer. Then we went to the Philadelphia office and toured the Princeton office. We sat down to lunch—he upped it some more. At the end, he matched the engineering offers.” Hillier’s impression of Morrison was that “he was charming and has a good backbone. He’s very definitive when he wants to be.”

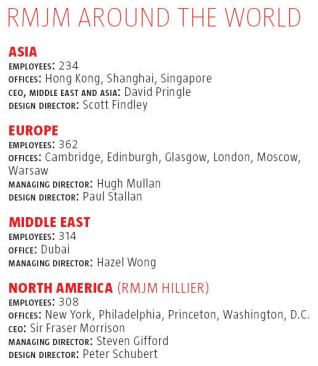

With the acquisition of Hillier, RMJM swelled to nearly 1,200 people working in seven countries. It was a marriage between two well-matched building portfolios: RMJM did more office and residential design while Hillier brought healthcare expertise (the firms were equally strong in education). The Morrisons organized the firm into studios that span offices, even oceans—the Global Education Studio, headed by Gordon Hood, works out of Cambridge and Princeton—and shuffled up its workers, sending Brits to New York and Americans to Edinburgh and Dubai. Today there is “more rigor in the business side,” Hillier says. With management paying closer attention to how work plans are drawn up and fees are assessed, he says, “I think we’re charging more realistic and [higher] fees than we were before.”

What’s more, “there’s been very, very little fallout” from the merger in the U.S. offices, Hillier claims, citing two reasons: First, there were no layoffs; and second, an ESOP (employee stock ownership plan), which owned “40-some” percent of shares in Hillier Architecture, meant that every employee received a cash payout. “The mail guy got $65,000 because he’d been here for 15 years. Everybody got something in the merger.” RMJM does not have an ESOP.

ARCHITECTURAL POLITICS RUN AMOK On a March morning in RMJM Hillier’s unassuming New York headquarters, which occupies the 24th floor of an Art Deco building on Seventh Avenue, designers hunch over their desks and the principals look out from their glass-walled offices. The staff is as cosmopolitan as you’d expect, but with a decidedly Celtic, and youthful, bent—even the principals.

“Early forties, late thirties, is where most of the senior people are,” agrees Morrison. “And that’s a fantastic advantage in an industry where there are a number of firms that have very senior management teams.”

Chris Jones, who leads RMJM Hillier’s new Urban Studio, and Peter Schubert, the firm’s U.S. design director, give me a demonstration of Glo, an “international architectural visualization and animation studio” within the firm. A Scottish member of the Glo team, Andrew Maxwell, still looking a bit dazed several weeks after moving here from Glasgow, runs the demo on his computer. And there it is, gleaming and heroic in CGI as time-lapse clouds dart over a virtual St. Petersburg, to the strains of Camille Saint-Saëns: the 1,300-foot-tall Gazprom tower.

In December 2006, RMJM won a competition to design the headquarters of Gazprom, Russia’s state-controlled energy giant, beating out the likes of Daniel Libeskind and Rem Koolhaas. Even at this early stage, the project, and RMJM’s design, had kicked up storms of outrage. The St. Petersburg Union of Architects protested the notion of a tower that reached three times higher than the historic cityscape, boycotting the selection process. And RMJM’s win was far from straightforward. The three architects on the jury—Norman Foster, Rafael Viñoly, and Kisho Kurokawa—had walked off (Kurokawa voiced his objection to all six of the designs being considered). The decision had been left to the rest of the jury and to the results of a public poll conducted by Gazprom through its website. New York Times critic Nicolai Ouroussoff inveighed against RMJM’s proposed tower as “a bone-chilling expression of corporate ego run amok” on an “obscene scale.” Since then, in 2007, 4,000 people, including the chess player Garry Kasparov, took to the streets in St. Petersburg to demonstrate against the project—now renamed Okhta Center—and UNESCO may strip St. Petersburg of its World Heritage Site status; it will vote on the matter in July.

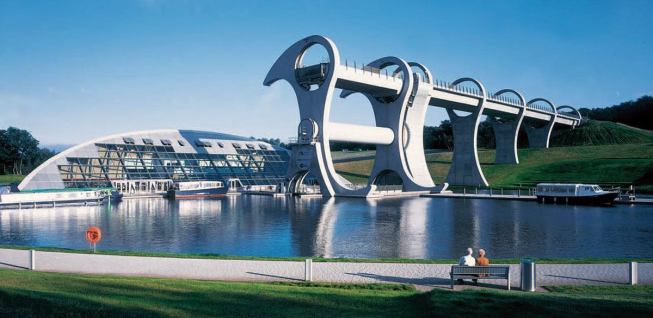

When asked about the project, both Morrisons are adamant that the design, by RMJM group design director and Falkirk Wheel alumnus Tony Kettle, is first-rate (“sensational,” Peter says) and wholly appropriate for its urban context. They point out that there’s already a 1,000-foot-high media tower in St. Petersburg and claim the impact of their tower on the skyline has been exaggerated by the media. “As far as Gazprom,” says Peter Morrison, “they’ve been fantastic. Great clients. Very supportive— we communicate well.”