Building Seagram

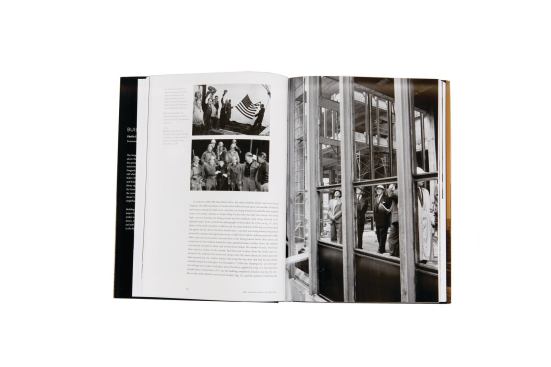

Philip Johnson, Ludwig Mies van Der Rohe, and Phyllis Lambert di…

It is a cliché, of course, to say that good buildings come from good clients and simply leave it at that. What we need is an attempt to get past that commonplace phrase and to begin to understand how these relationships evolve, as well as the particular combination of negotiation, willfulness, and good fortune that creates lasting architecture. (As Lambert writes, “Building Seagram is not a story of architectural or corporate power plays but rather one of unlikely convergences, extraordinary coincidences, and ironic turns.”)

In large part, this attempt should be seen as part of the broader and ongoing critique of the architectural superstar—the idea, obviously simplistic and yet supremely seductive, that buildings are created by individual visionaries working in isolation, drawing up genius building plans on napkins or scraps of paper lying around the studio.

Just as structural engineers have begun to step out of the shadows in recent years, with figures like Cecil Balmond making the case for the importance of their role, so should clients get some fresh attention as key actors in architecture.

Lambert’s chronicle suggests that clients have an impact on the design process not in an unwavering, steady way, but at a few key stages, or inflection points, in a building’s development. The first and most crucial is simply in finding the appropriate match between architect and project. “Today’s intense competition among corporations and developers to hire ‘signature’ architects was not yet in play” when she took over the selection process for her father, Lambert writes.

Today I am continually amazed by how often clients, even otherwise very savvy ones, pick prominent or fashionable architects who by personality or approach make a terrible match for the commission at hand. Lambert chose Mies in large part because she knew his ambition at that point in his career mirrored her father’s: He wanted to design the definitive postwar office tower just as Bronfman wanted to produce the definitive modern corporate headquarters, what he hoped would be the “crowning glory” in the careers of everyone involved. And constitutionally the two men—cool, reserved, decisive when necessary—made a good pair. When she introduced her father to Mies, she brought along her mother and Johnson, who both spoke German. The architect and the businessman, she writes, “took each other’s measure with genuine respect.”

Lambert’s other key contribution was to argue for the added expense of certain materials or design elements that Mies considered central to the tower’s character but that were hard to justify to the accountants inside Seagram—and to judge when the exact time to make that argument had arrived. These features included the custom-made, 6-inch-deep bronze mullions on the façade (which Mies compared in look and feel to an old penny, and which darkened over time) and the particular, unusually spacious dimensions of the plaza. In the scheme of things, those details may seem modest; but together, as Lambert writes, they gave force to the final product—“the dark building in the city wedded at ground level, inside and out, to human presence and activity.”