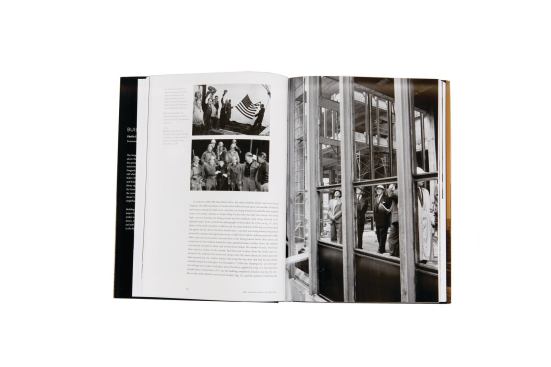

Building Seagram

Philip Johnson, Ludwig Mies van Der Rohe, and Phyllis Lambert di…

Since reading Lambert’s book, in fact, I’ve begun imagining a kind of parlor game involving architects and their patrons: Take a famous contemporary architect; rank his or her major projects in order of quality—or value, or impressiveness, or whatever metric of achievement you are most comfortable with; then rank his or her clients by level of, well, let’s say architectural intelligence. You will be surprised how often the two lists match up precisely.

Start with Renzo Piano, Hon. FAIA. His best American project, by a large margin, is the Menil Collection in Houston, where Dominique de Menil, in the 1980s, compelled him to adapt his already-softening high-tech style to her existing and careful vision for the museum’s campus in a low-rise Houston neighborhood. When I met Piano recently for breakfast in Los Angeles, I was halfway through Lambert’s book. I asked him near the end of the meal who his best client had been. “In America?” he replied. “Dominique de Menil. Very strong lady. Smart. She knew what she wanted.”

Piano’s most disappointing American designs, on the other hand, include the Broad Contemporary Art Museum at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where Eli Broad gave him a punishing budget to go with an accelerated construction schedule—sidelining the nominal client, LACMA director Andrea Rich. And with the forthcoming Whitney Museum near the High Line in Manhattan, the Whitney board’s quest for more square footage and a less stodgy location has led Piano to cartoonishly expand his approach, rather than focusing it or paring it down.

Or try Frank Gehry, FAIA. For distracted, deep-pocketed clients like Paul Allen, he’s produced disappointing and uneven buildings, such as the Experience Music Project in Seattle. Meanwhile, his Walt Disney Concert Hall, serially delayed and ever in doubt, was sharpened in the end to a brilliant result by three major figures on the client side: Lillian Disney, representing the donors; and the L.A. Philharmonic’s Ernest Fleischmann, and his successor Deborah Borda, representing the orchestra.

You can continue the list nearly indefinitely. Of the half-dozen houses Frank Lloyd Wright designed in and around Los Angeles, the finest by far is the Millard House in Pasadena, built for a client Wright had already worked with in Chicago, Alice Millard. Why is the Eames House better than every other building by Charles and Ray Eames? Because in that case Ray was Charles’s client, and Charles was Ray’s.

Why is Rem Koolhaas’s library in Seattle a finer achievement than Brad Cloepfil, AIA’s museum there? Because Seattle’s chief librarian, Deborah Jacobs, not only knew what she wanted in a library but crucially how architecture might be enlisted to deliver it, while the Seattle Art Museum was too busy concocting a complicated real-estate deal with Washington Mutual to focus on the particular details of the architecture of its new wing.