Camilo José Vergara

A year later, the National Trust came out with its most-endangered list, a media frenzy for which Heck says she was fully unprepared—no one from the Trust had given the archdiocese any advance notice. “The Boston Globe called. The picture on the [trust’s] homepage of an ‘endangered’ church was not even one that had been named closed.” On it went for three days, she says: “I think succinctly the word ‘mess’ would work.”

A more collaborative relationship between preservationists and the church is possible. The Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation plans to advise the local diocese on church closures. In September, the diocese announced its settlement of 32 abuse cases for $1.25 million. It was preparing to begin talks with the preservation group about the fate of 10 churches that were going on the market (the diocese has been trimming back its holdings since 1988).

“So often there’s a tussle between preservationists and the church, so we said, ‘Let’s try to find a way to work together,’” says Arthur Ziegler, the president of Pittsburgh History & Landmarks. “We realize you can’t keep all these buildings, and we recognize that you’d like to see some of them preserved.”

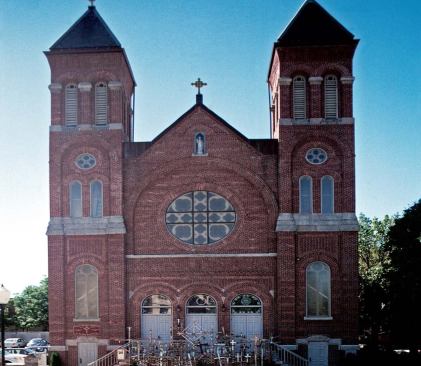

A House of God Becomes Affordable Housing On Centre Street in Boston’s Jamaica Plain section, the colossal brick walls of the former Blessed Sacrament Roman Catholic Church trump everything around them—a shady and recently gentrifying neighborhood of wood houses and small apartment buildings. Preservationists count the 1917 church among the best pieces of Italian Renaissance Revival architecture in New England. The church, its rectory, and its convent have stood empty since the Boston Archdiocese closed or “suppressed” the parish at noon on Aug. 31, 2004. Inside the church, most everything of ecclesiastical value has been removed. The absence of pews sends echoes through the eight enormous stone columns along the aisles, some of which have been stripped of their capitals. Beneath the soaring barrel-vaulted nave and the 135-foot-high dome, the eyes of painted prophets still stare down from the ceilings.

Bids are out to turn much of Blessed Sacrament’s three acres into affordable housing. Jaeger and other preservationists tend to view conversions of churches to multiunit housing as the most destructive possible outcome: With the two building types so at odds, the limitations of form are severe.

I walked through Blessed Sacrament with Peter Roth, the president of New Atlantic Development in Boston, who is also chair of the Boston Preservation Alliance and teaches in the graduate real estate program at MIT. New Atlantic is jointly redeveloping the property with the nonprofit Jamaica Plain Neighborhood Development Corp. (JPNDC), having together paid $6 million in December 2005. “More than we wanted to spend,” Roth says, “but less than the archdiocese wanted.”

To figure out how many apartments he can build inside a church, Roth says, he counts the windows. About 37 apartments will fit inside the church—it isn’t feasible to build up inside the dome. Then he works backward to figure out the price of each unit. To keep prices in an affordable range for the neighborhood’s median income, the sale price can’t go higher than $190,000. Development costs are about $385,000 per unit. The gap requires a subsidy. He has applied to the city and been denied twice. The state requires matching funds from a private donor that don’t currently exist. “So the church is phase two,” he says wryly.

For now, there is plenty going on in phase one. One of two former parish school buildings is being sold to its longtime tenant school. The other is in renovation to become a community center—in September, a new sprung floor was being installed inside a spacious dance studio. The wood-frame rectory, on Centre Street, is moving 100 feet off its corner to make way for 36 cooperative apartments and a few small storefronts. The convent, perched up above high walls on an elevated corner of the site, will become 28 single-room-occupancy apartments run by the Pine Street Inn, Boston’s largest provider of services to the homeless. It will convert nicely, Roth says: “Small rooms, shared bath. That’s what a convent is.” Parking will go underground, and at the heart of the site, a shady green commons with a winding path will replace what is now an asphalt parking lot.

Richard Thal, the executive director of JPNDC, works with 40 other staff members in a warren of crowded, harshly lit offices in the neighborhood’s old Samuel Adams brewery complex. His group, backed by hundreds of neighbors and former parishioners, came to see its bid to buy the church (versus market-rate bidders) as deliverance for the property itself.

“This was very emotional for lots of people in the neighborhood,” Thal recalls of the church’s closing. “Parishioners were outraged at the Catholic Church. People had a lot to get off their chest.” JPNDC had already been working on redeveloping a large neighborhood area. “The plate was really full. But when we learned it was coming on the market, there was unanimity on our board, including exparishioners, that we can’t sit by and let [the church] become luxury condos,” Thal says. Over the past five years, he explains, 200 rental apartments in the neighborhood have turned into condominiums, squeezing out many lower-income residents and turning affordable housing into a renewed rallying concern among a historically activist population.

“We had to appeal to the church’s better angels to help benefit the broader community” over maximizing the sale price to a richer developer, Thal says. “It was the church that called attention in the late ’90s to the affordable housing crisis as a moral problem,” he adds pointedly. “They laid the groundwork.”

The Closures to Come Around the country, yet more dioceses are bringing their accounts to heel by selling church property. The Archdiocese of Los Angeles recently settled with sex abuse plaintiffs for a record $660 million and is selling its headquarters on Wilshire Boulevard. Church officials have said the settlement will require the sale of between 30 and 50 church “non-parish” properties in its domain. In September, the archdiocese provoked public outrage when it began evicting three nuns from a small convent on the poor side of Santa Barbara.

Activists there may find Boston’s example instructive. For the last three years, Boston’s planners, politicians, and neighborhood groups have had to race to help shape the future of former parish sites toward purposes never before imagined, angling among their own various interests and with the church’s leadership as to what the most generative use would be for the community versus what price a site will fetch the church. But in Boston, as in other cities, the current real-estate glut has brought several church-to-condominium conversions to a halt.

After churches close, considerable work remains in desanctifying the property by removing ecclesiastical objects. Kathleen Heck reports that the archdiocese is flooded with requests for objects from other churches—many of them, not surprisingly, in the South and West. A new church in Yuma, Ariz., is receiving the altar, the reredos (a screen from behind the altar), and the baldachino (an overhead canopy) from St. Jean Baptiste in Lowell, Mass.

St. Jean Baptiste’s pews, as well as the altar and reredos of another closed church in Lowell, Sacred Heart, have gone to a church in Spartanburg, S.C.—whose priest was ordained at Sacred Heart. While churches in Boston close, the Spartanburg church is holding as many as four masses on Sundays.

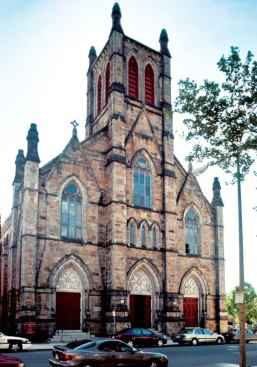

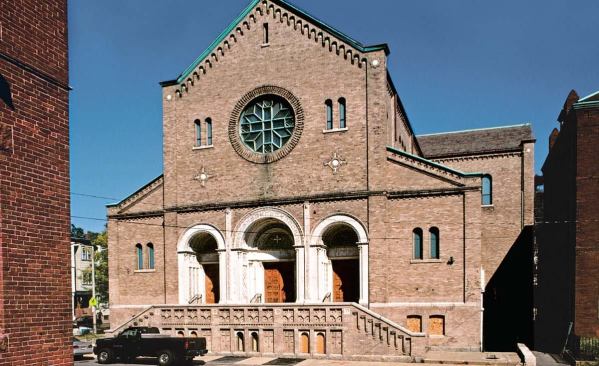

![Immaculate Conception, North Cambridge

Closed 2/2005

Sold to Serbian Orthodox Church

In November 2005 this church was sold to St. Sava Serbian Orthodox Church. It reopened two months later. Father Aleksandar Vlajkovic is awaiting delivery next June of the ritualistic wood screen, the ikonostasis, that will separate the sanctuary from the central nave; it is being carved by an artist in Novi Sad, Serbia. With the nearest Serbian Orthodox churches in Canada and New York City, ethnic Serbs come from far and wide to worship. On big feast days, Vlajkovic says, up to 700 people attend services. The white tent was erected for Serb Fest 2007. At last year's festival, says Vlajkovic, "a lot of [Immaculate Conception] parishioners showed up."](https://architectmagazine.stg.zonda.onl/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2025/06/tmpcec7-2etmp-tcm20-173335.jpg?w=653)