Camilo José Vergara

Nearly all of the major Protestant denominations in the United States are shrinking—Southern Baptist, Methodist, Lutheran, and Presbyterian congregations have all followed the larger population shifts of inexorable suburban migration as well as a sheer drop in membership. Catholicism is distinctive in that it is growing and yet closing churches. And for most Catholic worshipers, the loss of a church represents the shattering of the physical territory defined by parish lines. Historically, as the political scientist Gerald Gramm noted in the Boston Globe in 2004, parishes were assigned by home address and stood at the center of a community, around which “the lives of parishioners have revolved in fixed orbits.”

Many of those lives did not stay fixed in the racial swirl of the great postwar migrations. Working-class whites, the heirs of inner-city parishes built by their immigrant forebears, moved to the suburbs in the 1950s and ’60s. In their place came blacks, who established evangelical Baptist congregations but who themselves have increasingly gone suburban— the congregation of Shiloh Baptist Church, a black stronghold near downtown Washington, D.C., draws most of its worshipers from the sprawl of Prince George’s County, Md.

More recently, Hispanics, who increasingly favor charismatic faiths over Catholicism, have supplanted whites and blacks in some urban neighborhoods, as in the Delray section of southwest Detroit. In late October, that neighborhood’s Polish church of St. John Cantius, decimated to 200 mostly elderly members, celebrated its 105th anniversary with a final Mass before closing permanently. The Archdiocese of Detroit plans to sell the building.

“Our neighborhoods depend on many of these places surviving and the buildings being kept open and alive,” says A. Robert Jaeger, executive director of Partners for Sacred Places, a preservation advocacy in Philadelphia. Between worship services, he notes, churches provide a social binding that adheres well beyond their own walls. Lay charity groups like the Society of St. Vincent de Paul work from parishes to feed, clothe, and shelter poor people. Independent support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Al-Anon hold meetings in churches. “Virtually every parish has something,” says Kathleen Heck, who as special assistant to the moderator of the Curia has overseen matters large and small in the Boston archdiocese’s reconfiguration. “If the parish closes, the program moves.”

Keeping Churches Open and Alive The words “open and alive” have, however, taken on a number of different dimensions. Jaeger says that the most common way to reuse a church (and what most preservationists call the best use) is as a church, as in the case of St. James in Arlington and eight other Boston-area churches since 2005. Besides religious uses, the friendliest outcomes for the buildings seem to be as theaters or community centers.

Deed restrictions try to ensure that former parishes never house activity anathema to Catholic doctrine. New York City’s archdiocese won’t turn buildings over to become public schools because of sex education programs. In St. Louis, the new Ivory Theatre, which opened in September, is the former St. Boniface Catholic Church, built in 1860. It was one of about 30 churches closed by the St. Louis Archdiocese in a 2005 consolidation. The archdiocese nearly blocked the Ivory’s first show, titled “Sex, Drugs and Rock & Roll,” because the warranty deed with the developers barred, among other things, entertainment for “an adult audience rather than the general public” on the property. (After reviewing the show’s content, the archdiocese agreed to allow the show to open.)

Otherwise, little is guaranteed as shuttered churches move into their next lives. Historic landmark designations for Catholic churches are typically sought unilaterally by outside preservation groups or city officials. “The Catholic Church has not wanted to list their churches on the National Register generally,” says James W. Igoe, president of Preservation Massachusetts, a statewide group based in Boston. Such a designation can affect what the church does with its own real estate. “The Catholic Church never wanted to lose control of their property.”

Embroiled in its crisis, the archdiocese, Igoe says, rebuffed overtures by local and state preservationists to try to help plan constructive transitions for its closing churches. “We did get a couple of meetings,” Igoe recalls. “They didn’t provide much. We were really frustrated.”

Kathleen Heck, with the archdiocese, remembers meeting with Igoe and a National Trust staff member in early 2004 when parish closings were imminent but as yet unspecified. Heck says she turned the conversation around to historic churches that would remain open in any event but still suffer disrepair— how could the pastors and congregations be helped to protect those buildings? Funding is tricky, because public money generally cannot subsidize projects on religious properties. “I said, ‘What we need is a tool kit for pastors to save the churches they have,’” Heck recalls. “Two weeks later, I get this massive FedEx box. Inside are three huge 4-inch three-ring binders.” It was a new guide to preserving historic religious properties, assembled by a consortium of preservation groups, including the Trust and Igoe’s. “I couldn’t believe it was done in two weeks,” Heck says. “Way cool.”

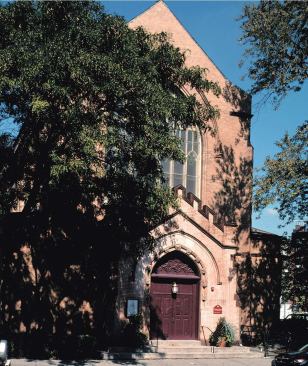

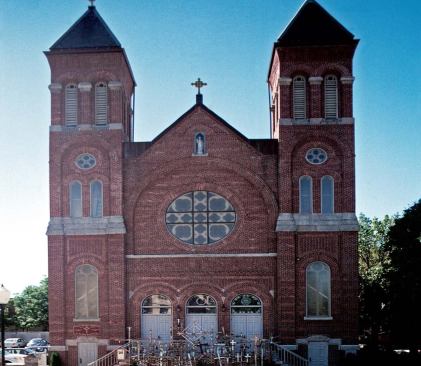

![Immaculate Conception, North Cambridge

Closed 2/2005

Sold to Serbian Orthodox Church

In November 2005 this church was sold to St. Sava Serbian Orthodox Church. It reopened two months later. Father Aleksandar Vlajkovic is awaiting delivery next June of the ritualistic wood screen, the ikonostasis, that will separate the sanctuary from the central nave; it is being carved by an artist in Novi Sad, Serbia. With the nearest Serbian Orthodox churches in Canada and New York City, ethnic Serbs come from far and wide to worship. On big feast days, Vlajkovic says, up to 700 people attend services. The white tent was erected for Serb Fest 2007. At last year's festival, says Vlajkovic, "a lot of [Immaculate Conception] parishioners showed up."](https://architectmagazine.stg.zonda.onl/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2025/06/tmpcec7-2etmp-tcm20-173335.jpg?w=653)