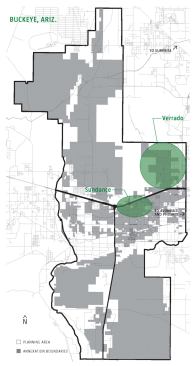

IF THE TOWN’S PLANNERS could have their way, Buckeye’s neighborhoods would look a lot like Verrado, one of its first major master planned developments, several miles northeast of the old downtown. Verrado drapes over 8,800 acres on an eastern slope of the White Tank Mountains, land that was formerly a proving ground for Caterpillar tractors. The development has attracted attention across the Phoenix area for its creation of an actual new town, with a main street business district (on Main Street) and better-than-decent production architecture in its houses and buildings.

It didn’t get that way by accident. Mass home builders generally design subdivisions as easily and cheaply as possible, which is why you see suburbs with oceans of nearly identical houses sequestered well away from the clots upon clots of retail plazas and pad-site restaurants on the blacktop heat islands that line the major roads. Driving through the outskirts of Charlotte or Sacramento these days is like watching the Flintstones, with all the same scenery rolling by in the background.

Verrado shows the influence of New Urbanism, a kind of “planned organic”—a seemingly spontaneous mixture of houses, condos, and apartments for all kinds of households that will, when done, salt in several hubs of stores and services among them. Although most of the home builders putting up houses in Verrado are production builders, they’re having to behave differently here to get a piece of the place.

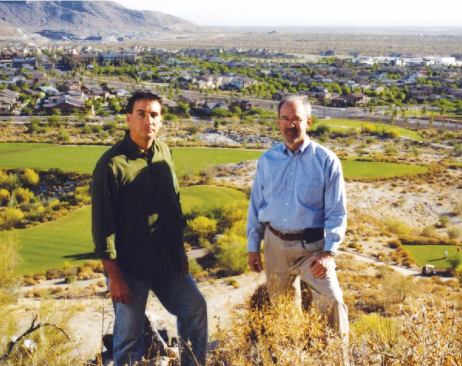

The developer, DMB Inc., is giving the builders multiple smaller sites on which to work. JT Elbracht, an architect (and Taliesin West alumnus) who is Verrado’s director of community design, pointed out the arrangement on a large-scale model in Verrado’s homey welcome center. “Instead of letting [builders] put 200 houses over there all in one spot, we said, ‘Put 30 over there, 40 over there, and 20 over there,’ so it disperses. This way, you get big houses next to medium houses next to small houses, like small towns have.”

The Main Street configurations were practically alien to the retail tenants in the town center. CVS wanted to build a pad-site store. “We talked to them and talked to them and said, ‘Guys, we’re not going to let you do that,’ ” Elbracht recalled. And DMB didn’t; the new CVS resides in a nicely detailed arcade storefront faced in stucco.

Across the street, the local grocer, Bashas’, initially objected to DMB’s requirement that it have entrances on three sides to make it more engaging to folks walking by. Citing the risk of theft, Bashas’ officers said, “ No, no, only two. Absolutely only two,” Elbracht said. “And we said, ‘OK, do this, guys: Put the doors in, and, if it doesn’t work, you can lock the doors.’ ”

Robert Kubicek, a Phoenix architect responsible for about two dozen retail projects within Buckeye, designed that Bashas’ store, which measures 16,000 square feet in a Main Street building with apartments overhead. The biggest problems, he said, came in trying to keep the store from bothering upstairs tenants with noise and exhaust. His clients at Bashas’ balked at the three-doors idea because “like everybody else, they want a little bit of control,” he said. But the doors seem to work fine. “It’s been very successful,” he said, and has compelled Bashas’ to look anew at putting stores in densely built sites.

Elbracht reserves special bragging rights for the new Verrado High School, just outside the town center. The school’s design (shown opposite, top right corner)—an industrial turn on Frank Lloyd Wright—is conceptually head and shoulders above the typical suburban school building. Massaging the school project along the lines of Verrado’s vision took some doing because the school is a public entity. “The school district gets its money from the state,” Elbracht said. “They only have so much, and we did a collaborative process with them to get a great-looking school that didn’t cost them or the taxpayers any more money.”

A LEED silver certification is pending for the school, based on its energy efficiency and recycled and locally bought materials, among other features. The firm that designed it, Orcutt|Winslow in Phoenix, also designed Verrado Middle School nearby and is working on a new elementary school for the community. David Schmidt, the project architect, said he had his doubts about fulfilling DMB’s wishes for a showcase high school.

“At first, I thought, I can’t afford to follow [DMB]” because of the costs that could entail, Schmidt said, adding that the developer’s dictates initially seemed like interference, though DMB was donating the land and chipping in $2.25 million of the school’s $40 million budget. “We finally started to look at it their way to try to come up with a design.” Looking back, he said, “I’m glad DMB pushed us the way they did—it gives the school a different character.”

Buckeye officials are also impressed by Verrado, which has had a considerable influence on them. “I’ve never seen how much planning thought goes into it—the effort that they’ve put into planning,” Dasgupta said. In particular, she cited the new fire station being designed for Verrado by Perlman Architects, an arcaded, hipped-roof building that will look as if it’s been there since the 19th century. “The fire station the town is going to get out of that effort is just a gorgeous building,” she said.