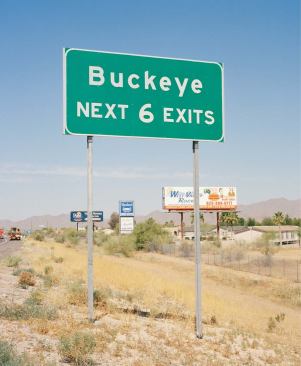

The bursting of the housing bubble has slowed down home sales and also slowed the pace of housing-permit approvals and inspections around Buckeye. But “slow” is relative. In 2000, the town issued 76 building permits, or about 6 per month. In 2005, it issued 4,549, or about 379 per month—at one point, on Rohrback’s count, his staff was performing 300 inspections a day. Last year, the number of permits issued dropped to 2,888, about 241 per month.

We left Tartesso West—where we saw exactly one human being out walking the streets on a hot afternoon —and drove along the empty parkway and turned left into Festival Ranch, Buckeye’s northernmost master planned community. The 10,000-acre property is being developed by Pulte Homes’ subsidiary Del Webb to include 24,000 housing units around a 23-acre village center. So far, there are two completed housing developments, including the new Sun City Festival for retirees. Sun City Festival residents can shop at a new Safeway, fuel up at a new Shell station, and go chipping at the Copper Canyon Golf Club. Near the entrance, there are plans for a 155,000-square-foot retail center anchored by a Fry’s Marketplace grocery store.

On the way to Festival Ranch and back, we passed by Douglas Ranch, by far the largest of Buckeye’s approved master planned communities. The former cattle ranch encompasses 32,250 acres and will have 83,266 new dwelling units when fully built. For the moment, it is as empty as it ever was, and some of the roughest land you’ve ever seen.

“WE DON’T WANT to become a bedroom community,” said Bob Bushfield, a planner who is the director of community development for Buckeye. He looks askance at what has happened to so much of the Phoenix metro area, a suburban monoculture of tract homes built exclusively around the automobile. “That’s not our goal.”

When Bushfield came to Buckeye several years ago, he was the planning department. In 2005, he hired Suparna Dasgupta as his assistant director, and she is in charge of planning and zoning, with oversight of community master plans. “It’s just exploded since about 2003, when things really took off,” Bushfield said. The department now has a staff of seven people, if you count Marcotte, who has another 10 inspectors out in the field.

To avoid the bedroom-community syndrome, Bushfield, Dasgupta, and their staff must fit together many kinetic pieces of an urban puzzle at once to try to ensure that people who live in Buckeye generations from now don’t find themselves trapped in neighborhoods without stores or places to work—or in a town that can’t sustain its own infrastructure, education system, or, most importantly in the desert, water.

In January, the Buckeye Town Council approved a major update to the town’s general plan, which, in keeping with Arizona state law, guides all development in town. In May, the town’s residents were to vote whether or not to ratify the plan. Dasgupta, who managed the writing of the new plan, believed that voter ratification would be quite likely, because the plan had been developed over two years with copious feedback from stakeholders, such as longtime residents, new arrivals, farmers, developers, the chamber of commerce, and officials with Maricopa County and the regional planning agency, the Maricopa Association of Governments. By the time the process was finishing, people stood up at town council meetings only to praise the plan, Dasgupta said.

“It was unbelievable,” she added. “We had a minimum of 100 people at every public hearing. You never see that kind of participation. I would be lucky in my other job if I got 10 people to come.” (Dasgupta previously worked as a planner in Cincinnati.)

The plan follows the mandates of Arizona’s Growing Smarter legislation, passed in 1998 and beefed up in 2000, which requires local governments to enact development strategies with citizen input. The plans have to address the preservation of open space, the shaping of growth areas, environmental planning, the funding of development costs, property rights, and water supply. (Buckeye can pump groundwater for the next 100 years from the Hassayampa River aquifer.)

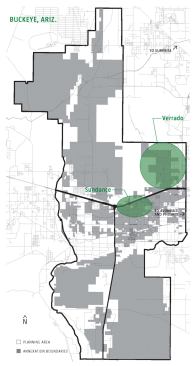

Growing Smarter has given the town’s planners an excellent excuse for policies that will not destroy the region’s natural ecology but that will also support population growth, if indeed the cake can be both had and eaten. Buckeye’s new general plan is written to work hand in glove with a massive transportation study by the Maricopa Association of Governments covering the Hassayampa Valley, which includes all of Buckeye.

The Hassayampa study contemplates more than a dozen new major parkways and freeways in addition to arterial routes and projects possibilities for pedestrians, bicyclists, bus riders, and light rail users. The Hassayampa study has also helped Buckeye determine where it will situate areas for new urban growth—mainly in an area south of Interstate 10. The planning staff is working to concentrate major office centers in a medium-density expansion of downtown. On planning maps, the location for this city center would sit next to four proposed freeways, the prospects for which would seem, most other places, simply starry in their scope. In Buckeye, nobody seems to doubt that they will come true.