The start of a new year offers a prompt to take stock of past accomplishments and future goals for individuals, firms, and industries at large. Continuing ARCHITECT’s annual tech to expect coverage, nine leaders in design, architecture, and technology pinpoint below the most significant, tech-related developments to arise in the profession over the last decade, and where the opportunities lie in the next 10 years.

David Benjamin

Founding principal, The Living, an Autodesk Studio, New York

Associate professor, Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Preservation and Planning

Courtesy The Living

David Benjamin

What’s changed: Generative design was the headline story of the last 10 years. But another important story was grown materials. A combination of advancing technology and environmental awareness led to many exciting applications of building materials that are grown by living organisms rather than manufactured through the traditional processes of “heat, beat, and treat.”

Wood, in the form of mass timber, is the most mainstream and the most advanced grown material, and the past decade has seen incredible advances. Yet developments in many other grown materials—cork, wool, bamboo, bio-plastics, concrete grown from bacteria and sand, and bricks grown from mycelium (the root-like structure of mushrooms) and agricultural waste—have also occurred.

Compared to conventional building materials such as steel, concrete, and plastic, these materials generally use fewer non-renewable resources, involve less embodied energy, and have the potential to sequester carbon. Also, they often lead to better work conditions, less pollution during their extraction and production, and quieter and safer construction sites. This is especially critical in the context of the climate crisis.

Not only can these materials make better versions of bricks and columns, but they can also redefine architectural elements themselves. In some of the most revolutionary applications, these materials can be kept alive in the built environment to offer entirely new properties. For example, living mycelium blocks can self-heal and bind to each other during construction, acting as both brick and mortar in the same object. The potential of these materials can be amplified by new processes like computer simulation and machine learning. At the same time, they involve a striking return to low-tech techniques and principles.

Courtesy The Living

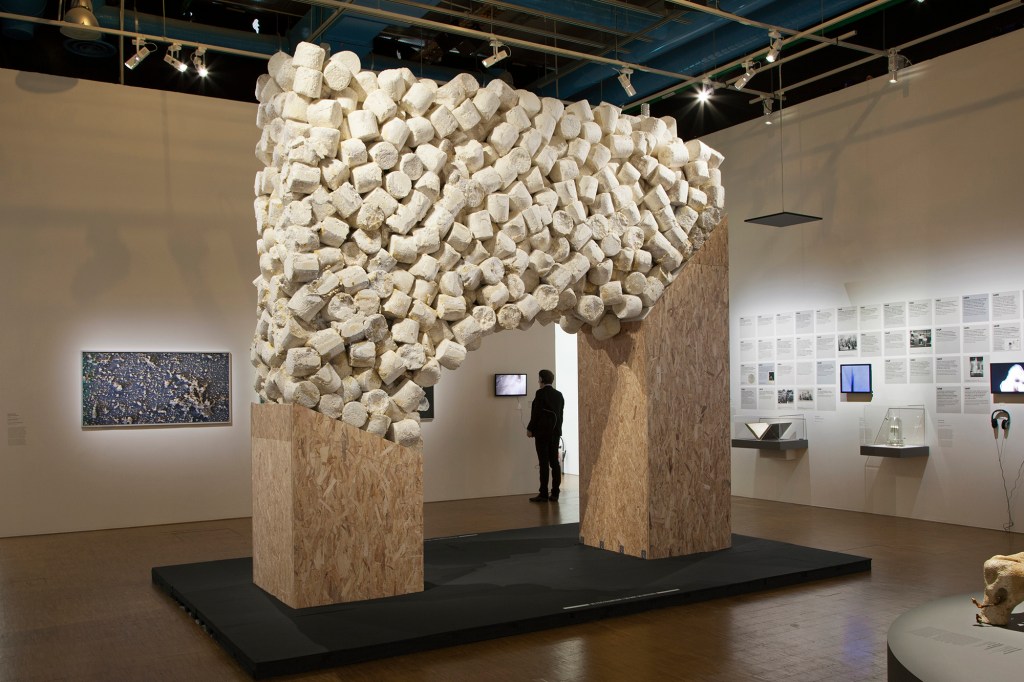

Bio-welding of mycelium material in The Living's exhibit “Jammed Bio-Welding” for the 2019 Milan Triennial, entitled Broken Nature

What’s next: The opportunity for the 2020s is to directly address the demand for rapid urbanization, new construction, renovation of aging structures, and the unprecedented forces of climate change. For the next 10 years and beyond, 13,000 buildings constructed each day. This is our chance to rapidly transform the industry from zero decarbonized buildings to 100%.

Robert Yuen, Assoc. AIA

CEO and co-founder, Monograph, San Francisco

Courtesy Robert Yuen

Robert Yuen

What’s changed: One of the most significant tech-related developments to arise in the design profession is the growing accessibility to technology we see pervading the entire industry. The pace at which technology is becoming more accessible and ubiquitous is unprecedented and exponentially accelerating.

But the single most significant tech-related development is the value of design. The low barrier of entry to pick up a new technology has led to advancements in how we are fundamentally educated as architects and how we are optimized for the design and business decisions we make every day. User experience (UX) and user interface (UI)—now critical design roles in companies—have the sole purpose of helping to make the accessibility of technology front and center.

What’s next: The following decade will offer unparalleled opportunities for architects to learn, build, and deploy software within the design and management spheres. We’ll see not only a growing trend in internal software solutions, but also the emergence of tech companies started and led by architects. UpCodes is one such example; its product and tools help to manage building codes, avoid project delays, and clarify building requirements.

Kirsten R. Murray, FAIA

Principal and owner, Olson Kundig, Seattle

Rafael Soldi

Kirsten R. Murray

What’s changed: The real game changer has been the advent and development of 3D modeling technology. When they were new, these technologies held the promise of better integrated design, reduced waste throughout the design process, and an increased ability to test the performance and behavior of our designs throughout the process. Now we’re seeing that promise come to fruition. It’s changed the way we work.

This technology has also democratized the design process. As a tool, 3D modeling allows for a kind of collaboration with team members that improves everyone’s ability to work together and contribute to the final product. It’s certainly affected our ability to collaborate with clients; now they can see and experience spaces more easily, even early in design.

What’s next: There’s an opportunity for architects, especially in America, to be actively engaged in the process of revitalizing our cities by creating more density and improving pedestrian-oriented connections. The general population—as well as from people such as developers who know the market well—is aware that opportunity exists here, and that these are the kinds of places we want to make. It’s a real synergy of interests for architects, planners, and developers.

In Seattle, we’re seeing interest in redeveloping the quasi-abandoned financial district. These buildings were originally developed because they were convenient to the highway, but modern populations are less car-dependent. We are now revitalizing the surrounding neighborhood by enhancing the pedestrian-oriented experience.

When I came to Seattle, density and revitalization were happening in neighborhoods adjacent to downtown—South Lake Union, the stadium district. Problems in those formerly industrial areas were easier to solve, so development happened there, and they drew people out of the city core. Now we’re working to make the city more accessible and more livable—introducing nightlife, culture, housing, and jobs—so we don’t end up with just abandoned financial districts.

Jonathan Massey

Dean, Taubman College of Architecture & Urban Planning, University of Michigan

Courtesy Jonathan Massey

Jonathan Massey

What’s changed: The past decade has seen intensified integration of design into data-based processes and economies. Our eyes and aesthetic sensibilities are trained algorithmically by Instagram and Pinterest. Airbnb teaches us to furnish our bedrooms and homes for the aggregated preferences of short-term renters. WeWork is testing the effectiveness of machine learning at laying out office floors based on user-generated data. Katerra aims to rationalize the building supply chain by feeding data on construction and operations upstream into development and design.

GIS (geographic information system) has supported data-based development, planning, and design at the urban and regional scale for decades, but the tracking of activity across digital platforms and urban space is putting data at the center of urban design and governance. From Hong Kong and Kashgar, China, to London and Toronto, the generation and control of urban data are prime terrain for politics and design.

What’s next: Data-based methods and businesses are disrupting architectural practice. Let’s leverage that to address the shortcomings of our field as identified by The Architecture Lobby, AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee, Who Builds Your Architecture, and other advocacy groups. By targeting tech disruption at underpaid design labor, disparate outcomes for women and people of color, and exploitative construction practices, we can build the more equitable profession our society deserves.

Gui Talarico

Software engineer and creator of AecStartups.com, San Francisco

Courtesy Gui Talarico

Gui Talarico

What’s changed: The most significant development is the increased interest and resource allocation from venture capital and technology companies into AEC industry products. Over the last few years, we have seen a major increase in funding and talent allocation to create tech solutions that overlap with traditional AEC services from products that replace test fits, such as Floored, Saltmine, and TestFit.io, to companies that create physical products that eliminate the need of hiring design and engineering services all together, such as WeWork, PlantPrefab, and Cover.

As clearly articulated in the May 2019 ARCHITECT article “Here Come Big Tech and the Venture Capitalists” by Daniel Davis, this trend will continue as we regularly see new AEC startups, as well as companies like Google, Tesla, and Amazon enter the AEC industry.

What’s next: The knowledge and skills of designers and architects will increasingly become packaged into tech products. While some typologies will continue to rely on traditional AEC service models for a bit longer, others will see clients and industry talent flock to vertically integrated products that bypass it. For example, enterprises might lease with WeWork instead of designing and building their own offices; or families might buy a prefabricated house instead of hiring an architect.

AEC experts will be critical to ensuring these new companies and products incorporate the best possible solutions from our disciplines. While working at design firms was once the primary path for young professionals, we can now apply our skills to help develop software and algorithms that encode the best solutions into reusable tech products.

Sandeep Ahuja

CEO, Cove.Tool, Atlanta

Courtesy Sandeep Ahuja

Sandeep Ahuja

What’s changed: Over the last decade, BIM workflows gradually replaced 2D drafting. The amount of BIM data generated sparked a paradigm shift in architecture to data-driven design. The digitization of practice accelerated toward the end of the decade to ensure that architects were able to leverage technology to eliminate mundane calculations and focus on design.

What’s next: Going forward, parametric tools and machine learning will come to dominate the next decade as architects work together to design net-zero buildings to meet the goal of carbon neutrality by 2030. With buildings contributing up to 40% of total carbon emissions, and more than 50% of projects still built without any attention to carbon, data-driven design is the major opportunity.

Ricardo J. Rodríguez De Santiago, Assoc. AIA

Global virtual design and construction specialist, BASF, Washington, D.C.

Brandon Tobias

Ricardo J. Rodríguez De Santiago

What’s changed: This past decade sowed the seeds of trends that would propel our practices into new digital territory. Object-oriented modeling, 3D printing, augmented reality, virtual reality (VR), embedded sensors, smart materials, and mobile devices, among other trends, are still in the early stages of substantially disrupting our professions. In that sense, assertions that “the end” of the traditional architecture practice has arrived have some validity. However, our focus should be placed on how we can channel our expertise through BIM-adjacent workflows and consequently gain a better seat at the proverbial “tech” table.

While BIM tools have been available in the market for several decades, the 2010s cemented the role of BIM as a data platform for the built -environment. This is particularly important as it allows industry stakeholders to start aligning in a similar methodology, value forecasting, and—one day, I hope—speak in a similar language.

Achieving the internet of things for buildings and cradle-to-cradle construction starts with open BIM. BIM as a data platform would allow for a greater degree of accountability, transparency, proactivity, humanism, and social responsibility. This is the way toward demonstrating the role of design as a vehicle to empower equitable communities and environmental stewardship.

What’s next: As big tech takes bigger strides in accelerating the convergence between manufacturing and construction, the opportunity for design professionals lies in the marriage between data and building sciences. As we become more familiar with artificial intelligence and generative design, our expertise in user experience and spatial relationships will be key. While other disciplines may be adept at commoditizing both our physical and digital footprints, the humanistic outlook and ethical values of design professionals will become pivotal.

Jenny Wu

Partner, Oyler Wu Collaborative, Los Angeles

Undergrad thesis coordinator and faculty member, SCI-Arc

Courtesy Jenny Wu

Jenny Wu

What’s changed: I’m most interested in technology that transforms and rethinks the design of the built environment, especially technology that allows us to realize buildings that would not be possible 10 years ago. As designers and architects, it is our obligation to challenge the discipline and move it forward. The software technology has matured significantly in the past decade, but hardware technology like robotics—which includes 3D printing at an architectural scale—is still at its infancy and will continue to be significant in the next decade.

What’s next: Artificial intelligence is an exciting avenue for architects to explore. I’m interested in how AI can supplement our design process and not replace it. Machine learning is powerful, but architects need to understand it so that the tool does not control the design.

Jon McNeal

Director and senior architect, Snøhetta, San Francisco

Courtesy Snøhetta

Jon McNeal

What’s changed: How architects consider studio time has drastically changed as access to cloud computing via smartphones and tablets has enabled designers to work remotely during site visits as well as from areas other than desktop spaces. This shift away from tethering designers to computers and desks toward mobile workstations has changed how teams collaborate, both within and across offices and disciplines: Design models can develop more rapidly and contain more detail than ever before; and reports and presentations can be edited from any place with a data signal.

While we can work from almost anywhere, fundamentally changing the meaning of a workplace, the shift into remote or mobile working blurs previously clear boundaries. These are changes that are occurring throughout many industries as workers demand more flexibility, putting pressure on workspace design to be more effective, adaptable, and engaging than ever before. We’re tasked with creating workspaces that enable and encourage in-person and remote collaborative work while attracting talented designers entering the workforce who want better amenities and the ability to balance work and life. It’s an exciting and new challenge, but at its core are many of the same questions that we ask ourselves for any project: What is the purpose of a space? And how can the design support what differentiates the site, culture, or client’s mission?

What’s next: Thanks to software and hardware advances, VR will finally becoming a viable technology for design development and visualization in the coming years. We’re just beginning to scratch the surface of what VR can contribute to design and communicating with clients. As the technology to create and view VR spaces continues to become more accessible, we’ll see an increase in interactivity with architectural design.