Practicing Lighting for the Green Market The sustainable, collaborative approach to lighting design can succeed for all players in the lighting profession and industry. The best way to explain this success is with a project study.

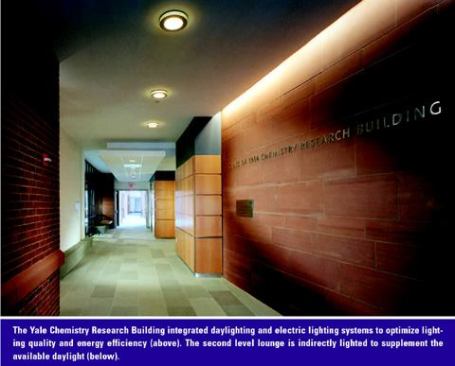

In 2003, I started a project with Cannon Design’s Boston office and design architect Bohlin Cywinski Jackson’s Pittsburgh office to design the lighting for Yale University’s new Class of 1954 Chemistry Research Building. Simultaneously, my team and I worked directly with Yale University Planning to guide this project through the LEED for New Construction process as Yale’s first LEED-certified building. Yale and the design team had already determined that this needed to be a well-lighted and energy-efficient building not only to attract world-class faculty and student researchers, but to help Yale manage its own co-generated energy costs and infrastructure.

Yale’s commitment to sustainable design enabled the design and construction team to actively collaborate on integrated strategies while staying within budgetary constraints. The project began with a charrette in the schematic design phase in which we identified natural light and fresh air as design priorities. Virtually all design decisions could ultimately be traced back to those attributes, resulting in an energy-intensive high-tech building that achieved LEED-NC Silver and 20 percent energy savings better than code (along with 40 percent water savings, but that’s another story).

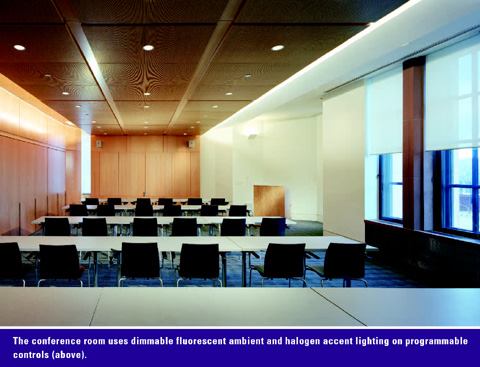

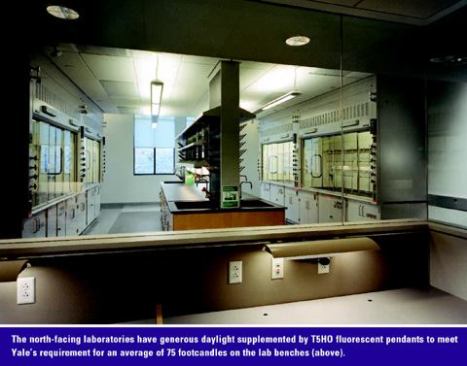

The lighting design portion of the project started with analyzing the daylighting. Our studies established that north-facing laboratories would have to have a generous and stable amount of available daylight, even with semi-transparent shades pulled down. The analysis also helped us optimize the window size and height to preserve thermal performance while improving daylighting performance. We were able to design a system that minimally lighted the circulation zone near the windows and to concentrate our direct-indirect lighting system over the lab benches, adding task lighting in labs needing an extra boost for specific visual needs. South-facing offices with abundant sunlight received the same luminaire, located near the interior wall. Glass lights in doors and sidelights allow daylight from labs and offices to visually connect corridors to the outdoors, but the electric lighting is a carefully organized system of linear wallwashers aligned with bulletin board panels. We advocated daylight dimming, but that was declined due to concerns for added complexity, especially since every space was occupancy sensored. The entire system came in at a fairly low connected load of about 1.1 watts per square foot and at a cost of about $6.00 per square foot (plus wiring and installation).

We selected luminaires based on performance and appearance, as well as our research into the manufacturers’ commitment to supporting professional lighting design and to their environmental management. That meant starting with Lighting Industry Resource Council (LIRC) member companies with environmental policies. We also considered where the luminaires were made, even seeking products from within 500 miles of the building, even though LEED does not currently include electrical equipment in its credit that encourages procurement from nearby vendors to reduce transportation energy use.

By testing the proposed lighting system in a full-scale mockup of an entire laboratory, corridor, and office bay, Yale enabled us to issue a well-defined lighting specification, modeled on the IALD Guidelines for Specification Integrity. We worked closely with several different sales agencies and the construction manager to ensure that everyone understood our design requirements and the need to work cooperatively. This avoided time-consuming and needless value-engineering and substitution requests. So Yale got what it wanted: a high-performance lighting system for a high-performance building. And the design team got the satisfaction of a system completed to specification and industry recognition in the form of a 2007 northeast regional IESNA International Illumination Design Award for energy and environmental design.

Many designers practice this way. Their relationships with clients, architects, engineers, manufacturers, and construction managers help them leverage good design into quality lighting systems. At the risk of seeming naïve, this cooperative and collaborative approach may be the specific key to a sustainable future and the lighting profession’s necessary evolution in response to the changing dynamics of design practice.

Mark Loeffler, IALD, LC, LEED is the associate director of Atelier Ten’s lighting design practice. He has more than 20 years’ experience with integrated daylighting and electric lighting design for high-performance buildings. A visiting lecturer in daylighting and sustainable design for Parsons The New School for Design, he also holds an MFA in architectural lighting design from Parsons. He is a current member of the A|L Editorial Advisory Board.