Tang Yau Hoong

Color Quality Scale (CQS)

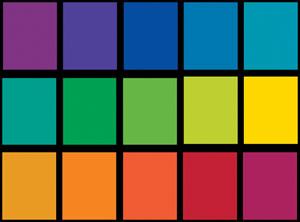

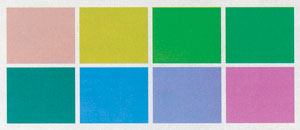

Instead of eight pastels (low-to-medium saturation), the CQS is based on a set of 15 colors with high chroma (high saturation) and spanning the entire hue circle in approximate even spacing. Rather than produce an average of eight pastel colors, as does CRI, in which an overall high score can be achieved despite one or two saturated colors appearing very poorly, CQS is calculated to ensure that significant color shifts for any single test color are reflected strongly in the final score. Lamps that enhance color contrast using RGB peaks or narrowband phosphors generate a higher CQS score, as CQS does not penalize increase in chroma (with some limits). CRI, on the other hand, penalizes shifts in chroma in all directions. The result is a simple zero-to-100 scale, with no negative values as is possible with CRI, and no values over 100, which is possible with other approaches. Finally, a CQS score also reflects well the poor color rendering of the sources whose color is too yellowish or greenish (chromaticity is way above blackbody locus), which CRI fails to address.

“We developed the Color Quality Scale so that its score agrees well with visual perceived color rendering and to fix the problems of CRI for SSL sources,” Ohno says. “CQS works in a very similar way as CRI, but when object colors are slightly enhanced—possible by RGB, RGBA, or other narrowband combinations—the score is not penalized. CQS is also designed so that the score will be lowered if one of the colors is rendered very poorly even though the average of all other colors is very good, which tends to happen with red. Red is critical for skin tone, and if red is poor, the whole color rendering will look bad even though all other colors appear good.”

NIST has proposed CQS as a new standard to the International Commission on Illumination (CIE), which currently maintains CRI as a standard and had formed a technical committee in 2006 to develop a new standard. The committee is currently focusing on two proposals, including CQS, but has not yet reached a decision. In 2010, CQS also was endorsed by the Department of Energy.

CQS offers the advantage of a single value that has a good possibility of becoming an International Commission on Illumination, and thus possibly an Illuminating Engineering Society, standard. And due to its DOE backing, it may become widely used. GAI offers the advantage of simplicity, adapting existing data to create a supplementary metric to CRI, which has served the industry for decades, for color-critical applications.

An additional advantage of CQS, Ohno says is that a single number score is produced, which simplifies application while making it friendly for use by general consumers and for labeling purposes. He points out that, while CQS solves the problems of CRI with SSL, it maintains consistency with most traditional sources.

“We understand that there is a strong resistance to change or drop CRI as it has been used for so many years, and it is also in some regulations,” Ohno says. “In CQS, we made only necessary changes from CRI to solve the problems for SSL sources, so the scores do not change much for most traditional lamps. The problem will be minimal when CRI is replaced by CQS.”

Gamut Area Index (GAI)

Mark Rea and LRC research scientist Jean Paul Freyssinier have two major recommendations to address the limitations of CRI. First, keep CRI, which is already established, but supplement it with a second scale, GAI, for color-critical applications such as retail installations. Second, limit the color-temperature designations to the four most commonly used in practice—3000K, 3500K, 4000/4100K, and 5000K—with tighter tolerances for deviation to maximize consistency among different products. These ideas were published in 2010 by the Alliance for Solid-State Illumination Systems and Technologies (ASSIST), an organization established by the LRC.

GAI offers an adjunct to CRI, not a replacement, providing a separate dimension to characterizing the color-rendering ability of a light source. It specifically represents the relative separation of object colors illuminated by a light source; the greater the GAI, the greater the apparent saturation or vividness of colors under the source. Light sources providing illumination high in both CRI and GAI, Rea says, are demonstrably better liked by viewers than light sources high in CRI alone or GAI alone. Rea notes, however, that while high CRI and GAI indicate hue saturation, which is good for color rendering, very high GAI can indicate color distortion. Unlike CRI, higher GAI does not always mean better.

“The two-metric CRI-plus-GAI system is more predictive of preference than any one-metric system,” Freyssinier says. “It uses the same radiometric data needed to calculate CRI, so no new measurements are needed. It embraces the well-established CRI without change. The two-metric, CRI-plus-GAI measurement system has been validated in several human factors studies. It is technology neutral; examples from every light source family already meet the two-metric criteria we proposed (CRI over 80; 80 under GAI under 100). And it can be used as a guide to develop new light sources and reduce uncertainty as to how well liked they will be for applications where color rendering is important, such as neonatal intensive-care units.”

Change Is Happening

Regardless of which method is eventually adopted by the lighting industry, CRI does not address the needs of SSL sources, influencing the direction of the continuing development of SSL technology and neglecting some potentially good products and opportunities. Change appears to be needed, although all standards take time. CQS offers the advantage of a single value that has a good possibility of becoming an International Commission on Illumination, and thus possibly an Illuminating Engineering Society, standard. And due to its DOE backing, it may become widely used. GAI offers the advantage of simplicity, adapting existing data to create a supplementary metric to CRI, which has served the industry for decades, for color-critical applications.

In the meantime, designers should take note when evaluating SSL products that those with good CRI may not render color as well as needed, while products with low CRI may render colors very well. The real test is to see for yourself. There is no substitute for developing firsthand knowledge of various products, and seeing the effect of a given light source in a mock-up prior to commitment.

Craig DiLouie, principal of Zing Communications, has been a journalist, educator, and marketing consultant in the lighting industry for more than 20 years.