Tim Hursley

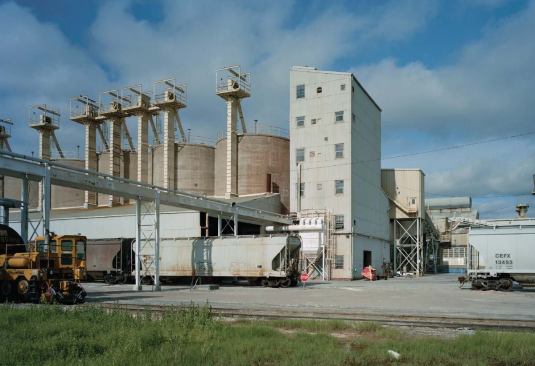

Broken glass to be recycled piles up at the mixing or "batching"…

3) Forming The process of forming the refined liquid glass into solid panels is one of mechanically manipulating the material around its natural propensity to be 0.271 inches (6.88 millimeters) thick. PPG’s Carlisle plant makes glass in thicknesses between 0.08 inches (2 millimeters) and 0.75 inches (19 millimeters).

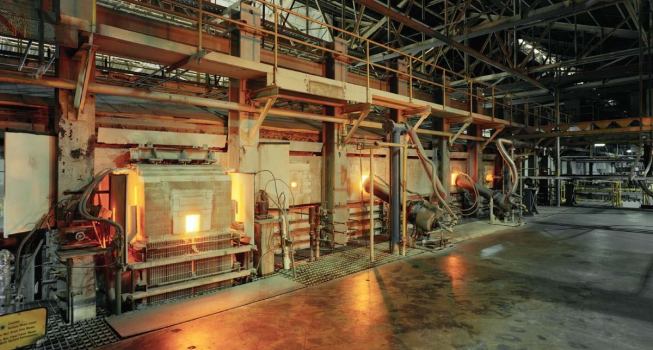

At the end of the refiner, the glass pours through an adjustable gate, called a “tweel,” that regulates its flow volume and depth to within 1/160th of an inch. It lands atop a bath of molten tin, on which it floats— hence the term “float” glass. The glass and tin don’t react with each other but stay separated; their mutual resistance at the molecular level makes the glass perfectly smooth.

As the glass forms a thin layer of pale fire—called a “ribbon”—on the tin bath, a series of adjustable guide wheels on either side hem it in to determine its width, which determines its thickness. Ranks of glowing orange electrodes help to keep the glass hot from overhead, as if it were in a broiler.

The flow of the glass has to be perfect, like “syrup on pancakes,” Kapura says, when it passes through the tweel and over a specially sculpted flat spout, or lip, onto the tin. “It all has to do with the viscosity,” Kapura says, and, thus, the temperature.

Kapura asks me to take out the Milky Way bar he gave me at the start of our visit, unwrap it, and grip the ends in both fists (which is why my notebook now has chocolate stains). He has a Milky Way of his own, although his is chilled. He grips it at either end and pulls it apart. It snaps cleanly in half. He tells me to do the same with mine, which had been in my pocket. The gooey caramel stretches to a strand as it pulls apart.

“The glass has to have the right stretch,” Kapura says. He can’t tell that story with a Snickers, he says, because the nuts in the candy would be like having flaws in the glass.

4) Annealing, Cutting, Packing

After the drama of melting and flowing, the glass remains mostly passive for the rest of the trip through the factory. As it forms and moves toward the “cold end” of the tin bath, a series of water pipes conduct heat away, taking the glass temperature down to about 1,150 F, at which point it enters a cooling oven known as a lehr.

The lehr is a rather long, enclosed passage in which the glass gradually cools down to about 300 F, a process known as annealing. A machine at the lehr’s far end automatically does a first check for flaws such as stones or bubbles in the glass surface before a stain inhibitor is applied from overhead. The stain inhibitor protects the glass from corrosion, which can develop if it is stored for a long time before fabrication. (This coating is eventually washed off.)

The solid sheets pass through the “slit-cut bridge,” a series of adjustable incisors that cut the panels into specified widths as it passes under them lengthwise. The panels then move beneath a second cutter called the “cross-cut bridge,” which scores them in the other direction, perpendicular to their path—though to make a straight cut while the glass is moving, the cutter is set at an angle. Directly afterward, they pass over a point called the “high roll snap,” which bumps the panels to separate them along the score lines.

Any pieces that are found flawed by the automatic inspection are discarded at the cullet drop, a kind of trap-door section of the roller line. Individual pieces are taken off the line to be inspected by the staff for any distortions. If the panels prove worthy, they flow forward for packing in one of two directions at the “mainline corner table,” which sends them either straight ahead or off to one side, depending on their size.

The edges are trimmed from the outer pieces and then inspected (the refuse is recycled as cullet), and the glass receives an application of a separating medium, a fine powder that allows the panels to stack without sticking together or scratching (saving on the tons of paper that used to be laid between them). An automatic packer picks the panels up by suction and stacks them in bulk.

Usually, the glass panels are sent to another line to be tempered by heat so that if they break, they crumble into small cubes that aren’t sharp. They may also receive specialty coatings here that modulate heat and light transmission, though some coatings may be applied later at a customer’s—i.e., a fabricator’s—shop. When it’s finished, the glass goes off, as white as water, to enclose homes, buildings, automobiles, and even aircraft.

Wherever it winds up, “the first person to touch the glass,” Kapura says, with a pause that suggests his continued amazement, “is the customer.”