Emily Hagopian

L to r: Designing Justice + Designing Spaces architectural associate Shelley Davis Roberts and co-founder and design director Deanna Van Buren

Deanna Van Buren didn’t plan to get into real estate development. The architect simply grew tired of projects stalling after the design phase. Following an extended engagement period, she would complete drawings for her clients—largely nonprofit organizations—which would then tell her, “OK, but we don’t have no money to pay for it,” she recalls. “And I thought, ‘Who cares if I’m making pretty pictures, talking to and getting the community excited about a project if we don’t know how to pay for it?’ So, I decided to start Designing Justice + Designing Spaces as a real estate and development firm.”

Based in Oakland, Calif., but with projects in cities as far-flung as Syracuse, N.Y., Atlanta, and Detroit, DJDS is a nonprofit multidisciplinary firm whose express mission is to end mass incarceration by realizing spaces dedicated to restorative justice and community building. Van Buren’s 2017 TEDWomen talk on designing a world without prisons has been viewed more than 1 million times. In addition to architectural design, the 18-person office offers services in real estate development and financing and increasingly occupies the driver’s seat on projects. “We’re trying to lead, not follow,” says Van Buren, who is the founder and executive director of DJDS.

On the surface, the DJDS campaign to end mass incarceration couldn’t be more different from, say, a company like Katerra, the hyper growth–focused construction technology startup, based in Menlo Park, Calif., that burned through billions in venture capital before going bankrupt earlier this year. And yet both entities illustrate the growing interest among architects, builders, and developers in more vertically integrated practice models, which offer designers more creative control and allow companies to take on more risks.

Taken together, these ventures represent an attempt to wrest the often disjointed—if not downright oppositional—forces of development, design, and construction into alignment to achieve a more seamless and successful design and delivery process. While Katerra’s high-profile implosion suggests that the building industry may not be easily disrupted, proponents of vertical integration say it can allow for reduced design and construction timelines, increased knowledge and communication among disciplines, decreased financial risk, and improved building performance due to its more holistic take on the building process.

For DJDS, integrating development and design has expanded what the firm can offer. DJDS uses its Concept Development Fund, a pool of philanthropic dollars that the leadership raises separate from a particular project, to fund its design and engagement work. “That vehicle is what’s allowed us to raise money to basically do what we want to do,” Van Buren says. “Without it, we would have been in situations where we’re trying to compete for RFPs and don’t have control over the process. So, it’s been really, really helpful.”

Emily Hagopian

Entrance, Restore Oakland, in Oakland, Calif., designed and developed by Designing Justice + Designing Spaces

Emily Hagopian

Restore Oakland, a restorative justice center in Oakland, Calif., designed and developed by DJDS

For Restore Oakland, a 2019 nightclub-turned–restorative justice and job training center, DJDS worked with the building’s prospective tenants—a mix of community organizations including the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights—first to identify and acquire the two-story, 20,000-square-foot Art Deco building. DJDS didn’t directly finance the purchase of the building, but it did help negotiate a yearlong due diligence period, Van Buren says, which gave the client group more time to raise the necessary funds and the firm a chance to organize community meetings and finalize the building’s design. Today, the site provides East Oakland with dedicated space for meeting, organizing, accessing social services, and participating in restorative justice circles (a process through which individuals work toward reconciliation outside of the traditional justice system).

For Grand River at 14th in Detroit, DJDS is playing an even larger role, leading the acquisition of up to 12 city-owned properties that will augment the recently renovated Love Building (named for a mural on its façade) to build what Van Buren calls a “creative oasis for social justice.” DJDS director of real estate development Sydnee Freeman says DJDS will likely issue a request for proposal for several vacant parcels adjacent to the building, but the firm will remain the long-term landowner. “Site control is critical to manifestation,” Van Buren says.

courtesy Designing Justice + Designing Spaces

Grand River at 14th (formerly The Love Building), Detroit, developed by Allied Media Projects, which will jointly occupy the space with Detroit Community Technology Project, Detroit Disability Power, Detroit Justice Center, Detroit Narrative Agency, and Paradise Natural Foods. Designing Justice + Designing Spaces and Sidewalk Detroit worked with AMP to involve community members in the development process.

Stephanie Kamera

The Love Building, Detroit

Stephanie Kamera

Grand River at 14th site visit, Detroit, led by DJDS co-founder and design director Deanna Van Buren

The trend toward vertical integration is occurring among firms at every scale, from DJDS’s single-office operation to national design-build behemoths like Chicago-headquartered Clayco to smaller, boutique operations like Solidspace in London, and to the Office of Jonathan Tate in New Orleans. Lamar Johnson, FAIA, founder and CEO of the Lamar Johnson Collaborative, which merged with Clayco in 2018, says the emergence of vertically integrated companies offering a combination of development, design, fabrication, and construction is only going to increase in coming years. “This is the delivery method of the future,” he says.

Some of the rhetoric around vertical integration is hyperbolic, which only emphasizes the deep cultural divide among AEC disciplines. For instance, the 2016 Archipreneur article “Reasons Why Architects Can Make Great Developers (or not?)” compared architects to an oppressed class finally claiming their “rightful position” at the apex of the building industry and referred to the rise of the architect-developer as an “emancipatory trend.”

Sam Fentress / courtesy Clayco

Upshore Chapter, a 149-unit mixed-use development in Chicago by CRG, Lamar Johnson Collaborative, and Clayco

Sam Fentress / courtesy Clayco

Upshore Chapter, Chicago, by CRG, Lamar Johnson Collaborative, and Clayco

Sam Fentress / courtesy Clayco

Upshore Chapter, Chicago, by CRG, Lamar Johnson Collaborative, and Clayco

Still, almost anyone in the industry will admit that the current process by which buildings are made is inefficient, cumbersome, and rife with opportunities for costly mistakes. A 2018 study by PlanGrid and FMI Corp. estimated that time spent on “non-optimal activities such as fixing mistakes, looking for project data, and managing conflict resolution” costs the industry as much as $177.5 billion each year—just in the U.S.

Often these mistakes are the result of an oversight or miscommunication between the architect and the contractor, for which neither party is incentivized to take responsibility. Faced with what has become a litigious, liability-obsessed industry, more and more firms are discovering the creative, financial, and environmental benefits that come with having a more active say in a project’s conception. “When you create these contractual relationships, the contract gives you a turf, and you become protective of that turf,” says Robert Jernigan, FAIA, a senior vice president in the LJC Los Angeles office and former managing principal at Gensler. In an integrated delivery model, there is no incentive to pass the buck. “All of a sudden, it becomes our turf,” Jernigan says.

LJC executive director Sarah Jacobson, AIA, agrees. “Problems happen all the time on projects,” she notes. “The difference on an integrated project is that we’re able to have more open communication about what’s going to be the best solution and not worry so much about protecting the interests of one organization.”

courtesy Lamar Johnson Collaborative

Wildhorse Village, an 80-acre multiuse development in Chesterfield, Mo., by CRG, Lamar Johnson Collaborative, and Clayco

courtesy Lamar Johnson Collaborative

Wildhorse Village, an 80-acre multiuse development in Chesterfield, Mo., by CRG, Lamar Johnson Collaborative, and Clayco

The nontraditional business model of Boston-based Placetailor, which describes itself as a “vertically integrated housing delivery company,” evolved out of its “do-or-die” mission to prove the viability of zero-net-energy housing. Managing director Colin Booth says Placetailor began in 2008 as a design-build firm, but when the owners couldn’t find clients aligned with their mission, they decided to bypass clients altogether. “Why would we spend the amount of money that we might on marketing or chasing RFPs that we might not get, when we could put that time and attention and money into buying our own project?” Booth says.

Like Clayco, which offers design through LJC and real estate development through CRG, Placetailor’s four divisions—design, development, build, and technology—operate as separate legal entities that are then members of the cooperative Placetailor Co-op LLC. This structure reduces financial risk but also allows the companies under the Placetailor umbrella a certain amount of autonomy, Booth says. “Each entity is intended to grow and shrink, succeed, and fail, and bring on partners of its own as it needs to.” At the same time, because they are linked by a shared mission, they can work together on larger and more long-term goals. “When it’s all the same company, you can decide where you’re making your money and where you’re not,” Booth says.

Generate / courtesy Placetailor

201 Hampden, Boston, by Placetailor, Generate, Studio NYL, and Bensonwood

Generate / courtesy Placetailor

201 Hampden, Boston, by Placetailor, Generate, Studio NYL, and Bensonwood

He points to 201 Hampden in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood, a five-story mixed-use building that Placetailor is currently developing, designing, and building in partnership with Generate, an architecture-and-mass-timber-design studio led by CEO John Klein, who also founded the MIT Mass Timber Design workshop. The 201 Hampden project, designed to meet both Passive House and Boston’s new Zero Emission Buildings standards, will use cross-laminated timber panels and prefabricated bathroom pods to reduce construction time, which is slated to begin next spring. If all goes as planned, it will become Boston’s first all-CLT building. If Placetailor was a less diversified company, Booth says, it would be less able to invest in such a novel project.

Among its many advanced capabilities, Placetailor’s “most important technology” is that integrated-yet-autonomous business model, Booth says. The building systems necessary to achieving a net-zero or passive house building are no longer new or complicated. “They’re all proven,” he says. “There’s no technical issues. It’s really an alignment of values and getting away from that industry momentum that always puts a barrier in front of achieving something better.”

Expanding into new territory inevitably comes with challenges. As demonstrated by Katerra, reinventing an industry as complex and entrenched as real estate development carries no small amount of risk—though industry insiders maintain that Katerra’s problems were unique to its singular focus on growth and are not inherent to vertical integration as a model. Architects interested in breaking out of their disciplinary box will need to develop new knowledge, skill sets, and linguistic capacities. “Working on a multidisciplinary team where everyone speaks a different language and has different experiences requires time and effort,” DJDS’s Van Buren says.

Most challenging, perhaps, is that without abundant precedents, designers are left to pilot new models on their own and test things as they go. The biggest lesson Van Buren has learned? “Get used to more lessons,” she says. “It never ends.”

courtesy Designing Justice + Designing Spaces

Five Keys Mobile Classroom, Oakland, Calif., a MUNI bus adapted into a mobile schoolhouse by Designing Justice + Designing Spaces

courtesy Designing Justice + Designing Spaces

Center for Equity, proposed as part of Reimagining the Atlanta City Detention Center, Atlanta, by DJDS. The yearlong citywide process encouraged local residents to contribute ideas and feedback on how to repurpose the former jail "to benefit the community and address its harmful effects," according to DJDS.

courtesy Designing Justice + Designing Spaces

Center for Equity, proposed as part of Reimagining the Atlanta City Detention Center, Atlanta, by DJDS. The yearlong citywide process encouraged local residents to contribute ideas and feedback on how to repurpose the former jail "to benefit the community and address its harmful effects," according to DJDS.

Sam Fentress / courtesy Clayco

Pfizer R&D Facility, a 295,000-square-foot center in Chesterfield, Mo., designed, built, financed, and leased by CRG, Clayco, and Lamar Johnson Collaborative

Generate / courtesy Placetailor

201 Hampden, Boston, by Placetailor, Generate, Studio NYL, and Bensonwood

Generate / courtesy Placetailor

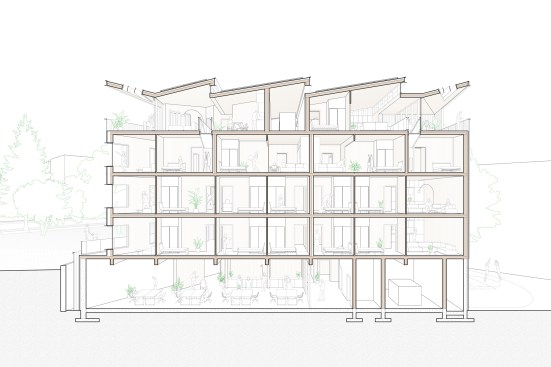

Perspective section, 201 Hampden, by Placetailor, Generate, Studio NYL, and Bensonwood

Generate / courtesy Placetailor

201 Hampden, Boston, by Placetailor, Generate, Studio NYL, and Bensonwood