Project Description

For more than 600 years, Seoul has been the capital and center of South

Korea. Roughly half of the country’s population lives in and around the

city, and almost all government ministries have long been centered

there. This concentration begat congestion, and after he was sworn in as

president in 2003, the now-deceased Roh Moo-Hyun

devised a plan to relocate many of the government’s hundreds of

offices. The moves would disperse people throughout the country and, not

insignificantly, push critical ministries out of Seoul and farther away

from the border with North Korea, which is just a 35-mile missile ride

away.

And while many ministries are being relocated to locations chosen

pragmatically—maritime agencies moved to the port city of Busan, for

instance—the Korean government is replicating the benefits of

concentrated government by relocating more than 40 of them to a brand

new administrative capital 75 miles to the south of Seoul called Sejong

City.

Much like the experimental architecture and urban planning of

purpose-built capitals like Brasília, Brazil, or Canberra, Australia,

the design of Sejong City is perhaps the largest test of a new approach

to citymaking—one that here starts with landscape architecture. The

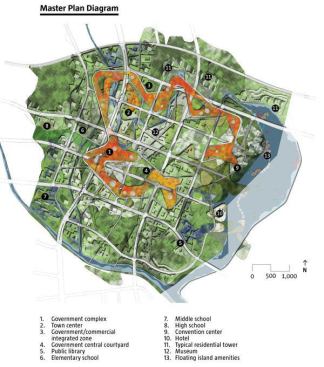

city’s competition-winning master plan was designed by a team including Balmori Associates, the New York–based landscape architecture firm run by Diana Balmori, who worked in concert with the Korean firm Haeahn Architecture and its New York subsidiary H Architecture.

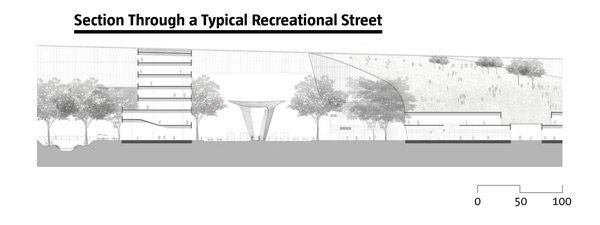

A grid of streets and transit runs through the center of the city, but

amid and over that street-level framework, the plan weaves a network of

green spaces dictated by the contours of the land, once hilly but now

flattened to make way for as many as 500,000 future residents.

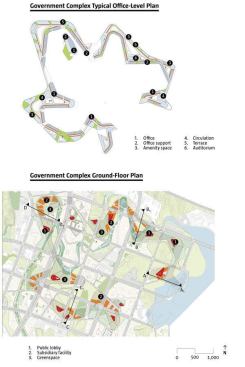

The centerpiece of the 667-acre plan and of the city itself is the

government building. Despite the dozens of ministries and agencies and

offices relocated to Sejong City, the plan—and the logic of the city

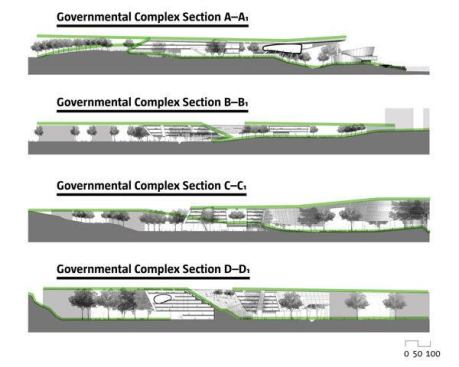

itself—is built around one large building. Balmori calls it the city’s

superstructure, and it is more landscape than architecture. Through a

series of sloping walkways, wide-open expanses, ramps and corridors, the

superstructure is an interconnected green space winding about two miles

in length and rising six stories high in places. It’s like a long, wet

noodle that slipped out of a bowl and onto a tabletop. It’s both smooth

and crooked. The government offices are contained beneath it.

“It’s a very unusual building in the sense that it has its open space

built into it,” Balmori says. “The superstructure in itself controls the

building.” The six-floor height limit was a deliberate choice, but it’s

something of an anomaly—Balmori notes that most of what’s been built in

Korea since the 1960s have been towers. On the outskirts of Sejong

City, where residential towns are being built, towers stand like

dominoes, proximate but disconnected. “There are no buildings that unify

the ground floor, and it all feels as if it’s hanging out in space,”

Balmori says. “[In the town center], we wanted something that was

continuous and gave shape to the space, but that also would give the

feeling that the city was very accessible.”

The city has been under construction since 2006, though politics

delayed most of the work until 2010. Balmori says the city is currently

about 80 percent complete, and should be finished by the end of 2015.

Outside of the central governmental complex, the rest of the city’s

buildings have been designed by other firms. The plan is guiding that

growth to emphasize the role that landscape can play in cleaning water

and reducing energy use. Balmori originally intended it to be what she

calls a “zero city,” where all water would be treated and reused locally

and all energy would be created on site. The energy approach wasn’t

adopted, but Balmori says the plan nonetheless proves landscape can be

the basis of an environmentally considerate new city.

“It didn’t really take shape until last year. I couldn’t see how many

of the ideas were going to come through,” she says. “And then last year,

‘Wow.’ I just felt so exhilarated standing on that roof and saying, ‘My

god, they actually followed the things we said.’ It felt so enormous.” —Nate Berg