Project Description

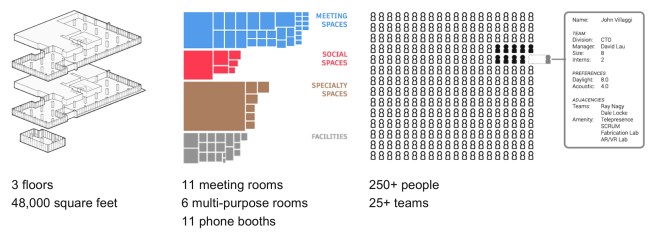

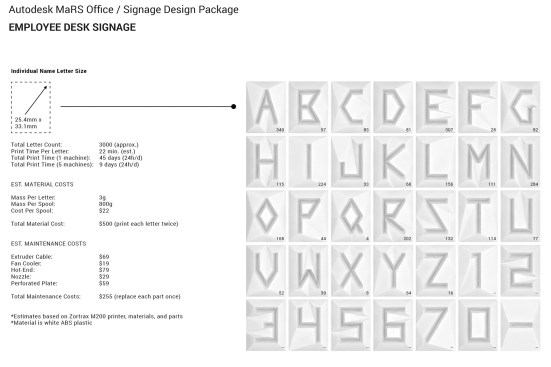

Autodesk’s new three-floor, 60,000-square-foot facility in Toronto’s MaRS Discovery District innovation hub has all the hallmarks of a high-tech office. Game room? Check. Flexible workspaces? Check. Telepresence suites? Check. But look beyond the well-appointed interior, and it becomes clear that The Living didn’t carry out your typical TI job. Instead, it used computational workflows and generative learning to optimize the design goals and create a space that takes into consideration the welfare of each of the 250-plus individual employees who work there.

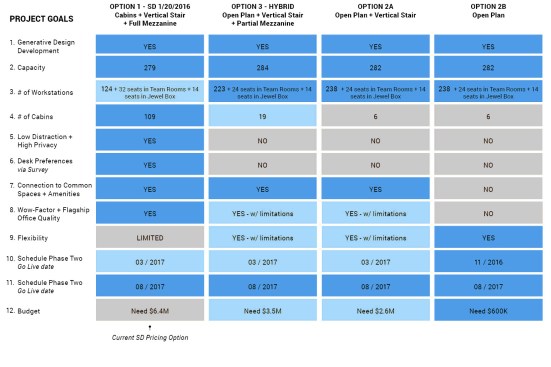

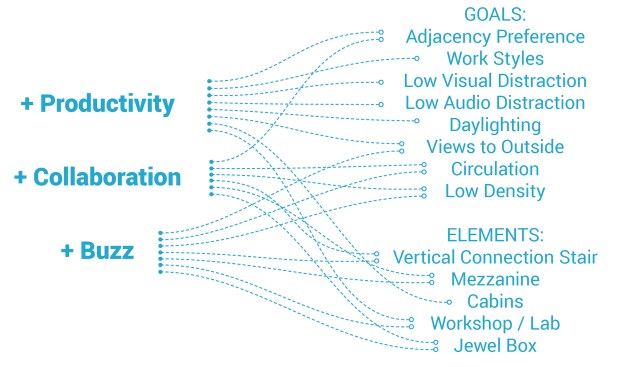

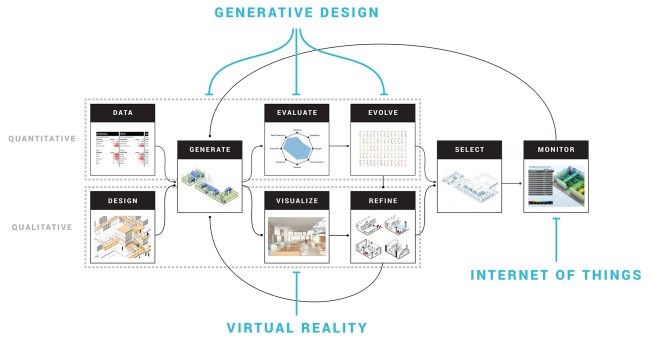

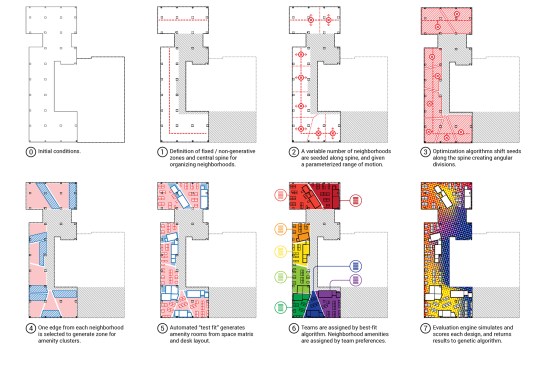

The first step in the process was to define the design constraints and objectives. Some variables were fixed and obvious: the dimensions of the floor plate, the placement of the column grid, and the number of employees, for example. Others required more planning, such as the number and square footage of the conference rooms and enclosed spaces. All of these were taken into consideration when determining goals for the space, such as access to daylight and views outside, and various levels of distraction and staff interconnectivity, or “buzz.”

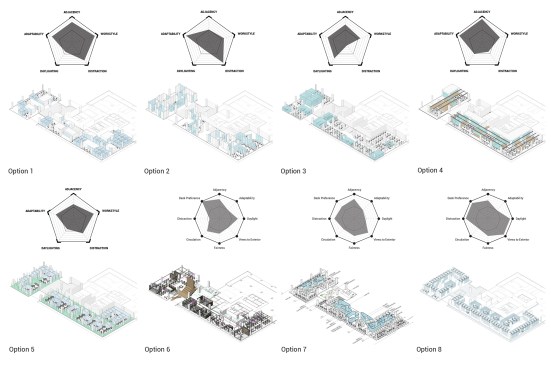

But The Living wasn’t content to plug quantitative design goals alone into an algorithm. “We were really excited to combine information about what kinds of space people like, what their experience is in different spaces, into a computational workflow and that is part of a measurable design process,” Benjamin says. The team designed two additional, arguably qualitative goals around adjacency preference and work style preference using data from a detailed survey distributed to every employee.

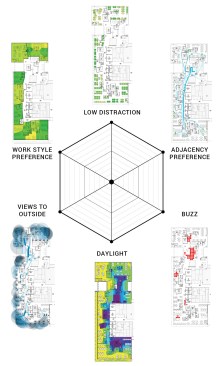

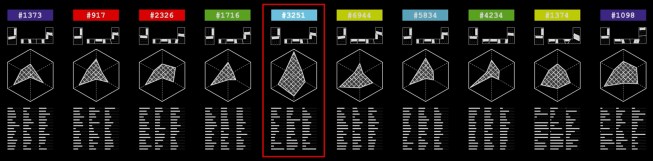

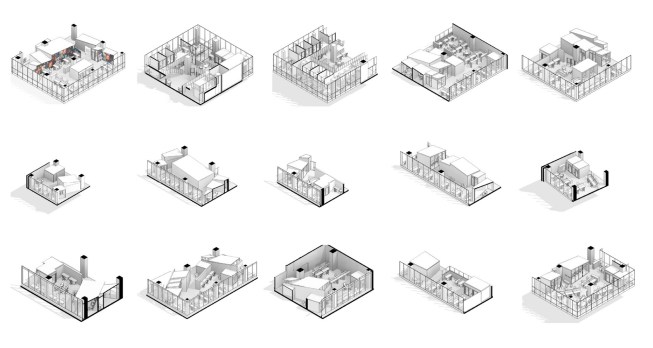

Each goal had its own algorithm. These were run through another algorithm that “evolved” the designs, creating 10,000 possible layouts for the space, each with a measurable outcome for each goal.

Because those thousands of design options come with data about how well they have satisfied each of the six goals, they could be compared against one another, ranked, and evaluated. The Living took 10 designs back to Autodesk to discuss with stakeholders. “We could say not only ‘Here are the different ways of solving the problem,’ or ‘Here are design options to discuss,’ but ‘Here’s the data behind what makes each one good according to the goals that we collectively agreed on,’ ” Benjamin says. “In the best case, it can make for a more inclusive decision-making process. Instead of removing us from human judgment, computation has the potential to make better debate about tradeoffs, instead of relying on vague notions of why one design is valid and another isn’t.”

The team chose one design alternative to use as a baseline for refinement, tweaked it based on late-stage feedback from employees, and chose finishes and graphics, evolving the scheme into the one that was actually built out. “We’re not purists about using computation to optimize objective efficiency,” Benjamin says. “We thought, ‘This is a system that could help us manage a lot of complexity, and we’ll see how far it can take us, and then we’ll see if there are other things we have to do to get us to the point that it’s a great design.’ We’re not saying computation is always better, just that it’s another way.”

It’s no surprise that Autodesk was keen to explore generative design processes for its own workspace—it’s a method that the software giant has been researching for years. The ultimate goal, says the company’s director of product strategy for AEC generative design, Anthony Hauck, is to make these processes available on a broad scale with its products. “We believe that there may be good design solutions that are never found because they are laborious to discover, and labor is at a premium. This is what automation is for. Can we take enough of the labor out of that exploration that we make it easy, and can we make it fun, so that we’re simultaneously improving peoples’ work lives and their confidence,” he says.

One of the advantages of having an experimental practice like The Living embedded within the company, Hauck explains, is that “not only does it give us an intellectual pipeline into a technologically advanced design practice, but also into how clients interact with that sort of practice. Because honestly, we think this is where practice is going—one way or another. So we’re getting a very early look, through The Living as a proxy in the market, at what the future of design might look like.”

Project Credits

Project: MaRS Office, Toronto, Ontario, page 106

Client: Autodesk

Project Team: The Living, New York . David Benjamin (founder and principal); John Locke, AIA, (project architect); Ray Wang, Danil Nagy, Jim Stoddart, Lorenzo Villaggi, Damon Lau, Dale Zhao

User/Research Team: Jeff Kowalski, Gordon Kurtenbach, Azam Khan, George Fitzmaurice, Thomas Heermann, Ramtin Attar, Hali Larsen

Facilities Team: Joe Chen, Stephen Fukuhara, Jenny Lum, John King, Sébastien Dubien, Shalini Adhopia

To see more projects from The Living, see our Q+A with David Benjamin from the January 2018 issue of ARCHITECT, part of What’s Next: Reprogramming Practice.