“I’m not an architect,” says Henry Muñoz III, “but I think I am an architect of change.” This is no modest claim, but then Muñoz, the 58-year-old principal and CEO of the architecture firm Muñoz & Co., is not given to understatement.

On a hot day in his hometown of San Antonio, Muñoz, wearing his signature reflector shades and a floral shirt, his hair lifted into a slight wave, is touring his studio’s latest project, a rehabilitation of the long-derelict San Pedro Creek. The initial phase opened in May, and already the new public space has had a significant impact, at least on one segment of the population. “The birds,” Muñoz says, pointing to a jet-black grackle lifting into flight. “They came back almost immediately.”

The now-complete half-mile segment of the waterway, renamed the San Pedro Creek Culture Park, is the first component of an anticipated three-part project; the next phase has already broken ground with completion expected in 2020. Muñoz’s firm has attempted to liberate the waterway from the concrete culvert to which it had been confined for most of the last century, adding lush wetland foliage to its margins and turning it into a less formal, more contemporary counterpart to the San Antonio Riverwalk nearby. Situated not far from where Spanish missionaries first founded the town in 1718, the park has an even more significant location within the city today. “This is really the connective tissue between the Mexican-American west side and downtown,” says Muñoz: The project will help weave the Latino neighborhood back into the city as a whole, a crucial objective for Muñoz and his studio.

Larry Servin

San Pedro Creek Culture Park

Larry Servin

San Pedro Creek Culture Park

Both are unusual hybrids. The firm was founded in 1927 as Eickenroht & Cocke; by the time Muñoz joined it in 1983, the studio, then operating as Jones & Kell, had risen to become a regional powerhouse. Today, its portfolio includes large-scale public works scattered all across Texas, with a strong track record of educational projects, public parks, and cultural facilities, all made possible by its staff of 43 who range from interiors specialists to city planners. As for Muñoz, he has no formal training, is not licensed, and came to the firm primarily in order to help its then-exclusively Anglo staff forge connections within the Latino community. “When I first started to work on this,” says Muñoz, “I didn’t really understand what I was doing.”

Twenty-five years later, he provides input on nearly every design while also bringing in new work. Yet his professional profile remains, to say the least, a singular one. This is because, since 2013, Muñoz has been the national finance chairman of the Democratic National Committee. His name appears on countless fundraising invitations and mailers soliciting contributions; his 2017 wedding to partner Kyle Ferrari was officiated by former Vice President Joe Biden. Since assuming the post, his work as an advocate has only intensified: He sits on numerous boards and councils (for the National Parks Foundation and the Cooper Hewitt National Designs Museum, among others), and in any given hour may field a half-dozen phone calls from the likes of DNC Chairman Tom Perez and actress Eva Longoria. “I just think this is a time of activism,” Muñoz says. Yet his architecture practice is not a sideshow, something separate and discrete; it is, in fact, central to the kind of change he’s trying to create. This unlikely pairing is not without its challenges (and its contradictions). But it does make Muñoz’s firm a fascinating case study in the architecture of engagement.

Al Rendon

Henry Muñoz III

Architecture for the Marginalized

Muñoz’s motives are a product of both nature and nurture. “The Fox,” as Muñoz’s father was known in political circles, was a major figure in civil-rights and labor struggles in the state for decades. Upstairs in the younger Muñoz’s home, an aging picket sign testifies to his father’s influence: The son, then 35, held the sign aloft during a protest—organized by the Fox—that demanded an increase in the local minimum wage. Having such a driven figure as a father did have its drawbacks. From an early age, Muñoz exhibited an artistic streak; his sister, Emily Bueche, recounts how the Fox reproached the boy for “always wanting to do everything,” volunteering for every extracurricular activity rather than focusing his efforts. Undeterred, Muñoz never relinquished this diffuse intensity, becoming an avid collector of art and design (with a special focus on the work of emerging Latino artists) even as he pursued his double-pronged professional life.

Muñoz first broke onto the political stage in 1992 with a three-year term on the Texas Transportation Commission under then-governor Ann Richards. Among his proudest accomplishments: a vast expansion of the state’s highway network in the underserved Latino-majority cities of South Texas. In the McAllen area, only a few miles from the border, Muñoz helped oversee the construction of a massive new freeway corridor spurring what has become a huge influx in commercial and residential development. “That was really the beginning,” says Muñoz, the first time he understood how the built environment could bring change to marginalized communities.

In the years since Muñoz returned to the private sector, his firm (first as Kell Muñoz Wigodsky, then in its current incarnation since 2013) has developed a portfolio of projects aimed at the underserved in Texas, especially the Latino population. Taking a page from prominent San Antonio artist and Chicano theorist Tomas Ybarra-Frausto—a close personal friend whose ideas, Muñoz says, “inform everything we do”—Muñoz coined the term “Mestizo Regionalism” to describe his approach. It’s less a stylistic genre than an abstract sensibility, one that aims to infuse every project with the richness and energy of America’s borderlands. As Muñoz puts it, Mestizo Regionalism entails “an expanded view of context as including culture—not merely buildings but the people.” In Texas, where Mexicans and Anglos (as well as African-Americans, Germans, and the French) have mingled for generations, communities are often no less diverse than their architecture, and all of Muñoz & Co.’s projects aim to expand the space of exchange and encounter.

Chris Cooper

Mission Branch Library in San Antonio

Chris Cooper

Mission Branch Library

Mestizo Regionalism can take a variety of forms. The firm regularly samples the palette and formal details commonly associated with the art and design of the Southwest: the 2007 Edcouch-Elsa Fine Arts Center in Hidalgo County, Texas, is faced in vibrant swatches of primary colors that recall the decorative traditions of Texas’ Mexican-American community, where storefronts are routinely enlivened with brightly painted murals and eye-popping signage. Likewise, the 2007 Museo Alameda in San Antonio (a museum of Latino culture, initially a Smithsonian outpost that is now occupied by Texas A&M University), which features a steel exoskeleton clad in a decorative metal lattice—a clear nod to the ornate grillwork that decorates older houses throughout Latin America. In other instances, the relationship to the local social and historical currents is a little less overt, as with Los Tomates, a border-crossing facility near Brownsville, Texas, that boasts a large trellis on the southern side. While providing shade to visitors, it also hearkens back to the tomato farm that once occupied the site. “A lot of this is storytelling,” says Muñoz, himself a polished raconteur who ensures that narratives like these are always embedded in the office’s work.

The Evolution of Mestizo Regionalism

The firm’s most recent projects demonstrate how that approach, not to mention the interplay between the detail-oriented staff of designers and their big-picture principal, has evolved. “Henry lets us take care of the way the building works, but there’s always these underlying ideas of his that carry through,” says Rene Lemos, Assoc. AIA.

Lemos joined the firm in 2008 and was on the team responsible for one of its latest undertakings, the Billy Earl Dade Middle School (BEDMS) in Dallas. Accommodating more than a thousand students in a facility of 213,000 square feet, the building is a long, oblong block in plan, with a glass-encased library to the east and a brick volume housing an auditorium and gymnasium to the west. Between the two, classrooms occupy the slender length of the structure with protruding oriel windows. The design has been such a hit, Lemos says, that “the only problem is everybody wants to use it,” with locals seeking to book the building for community events.

Chris Cooper

Billy Earl Dade Middle School in Dallas

Chris Cooper

Interior of Billy Earl Dade Middle School

While the technical requirements of the project required the design expertise of trained practitioners like Lemos, its cultural character—the values it sought to communicate—were very much within Muñoz’s bailiwick. He led an in-depth dialogue with the school’s predominantly African-American families in an effort bring their collective experience to bear on the design. After recognizing the important legacy of the school’s namesake, a prominent local educator, he worked with firm interiors specialist Joaquin Abrego to make the building a testament to Dade’s life and ideals. Together, they added artistic features that include a giant portrait of the educator, situated in the main entryway and composed of hundreds of quotes from its subject rendered in shades of black and white, as well as an elaborate sequence of discarded doors (most of them from demolished buildings in the area) covering the entryway walls, recalling Dade’s statement that “education is the door to opportunity.”

A similar artistic and cultural strategy has come to characterize the office’s nearly two-decade relationship with the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (UTRGV). The university’s campus in Edinburg, Texas, was originally designed by Houston-based architect Kenneth Bentsen as a series of courtyards surrounded by Louis Kahn–inspired monumental pavilions, their façades given a slight Southwest flavor with Mission style arches. Muñoz & Co. has designed a series of new buildings for the school, starting with the Engineering Building; their latest project, a new Science Building, opened over the summer. “It’s a good relationship,” says Geoffrey Edwards, AIA, the firm principal who oversaw the project, “and it’s allowed us to color outside the lines so long as we respect the overall architecture [of the campus].” The new building, a stout brick volume like its neighbors, harbors a surprise on its courtyard-facing side, with a blue brise-soleil of ribbed vertical strips and round dimple-like recesses.

Dror Baldinger

The Science Building at UTRGV

Dror Baldinger

The Science Building at UTRGV

Perhaps the firm’s most significant project at the campus is the 2005 Education Complex, a three-story building near the campus’s northeast perimeter that also a packs a few symbolic punches into its modest frame. Greeting visitors on the northern front is an elaborate entryway of decorative metalwork, “an abstracted concept of barbed wire,” Muñoz explains. Inspired by the work of a local artist, the door is a satirical take on the defensive infrastructure of the U.S.-Mexico border, here transformed into a symbol of welcome. Inside, the central elevator shaft features a series of dichos—traditional Mexican proverbs—etched into the glass, in both English and Spanish; as the elevator ascends, the two languages become increasingly intermingled, mirroring the linguistic cross-pollination common to the region.

Back in San Antonio, the office is now ready to embark on a restoration that’s been a pet project of Muñoz’s for years—the transformation of the long-empty Alameda Theater, a stunning 1940s Art Deco/Moderne structure that was once a hot spot for Spanish-language cinema, into the new headquarters of Texas Public Radio (one of Muñoz’s favorite causes). The firm will also be breaking ground next spring on San Antonio’s new federal building, a sprawling $117 million complex which Muñoz is determined to equip with a little artistic embellishment. Emerging from a meeting with his government clients, Muñoz seemed optimistic that his view would prevail, despite official resistance. “They were worrying about the budget,” he said. “But it’s going to happen.”

Marrying Architecture and Activism

Muñoz often expresses frustration at the current political landscape. “Some people will tell you there’s not enough opportunity in this country for all of us,” he says, a reactionary point of view he’s determined to combat. In 2017, under his leadership, the DNC succeeded in raising nearly $66 million, the largest haul in any off-cycle election in almost a decade, most of it from grassroots donors making small contributions. In the midterms, much to Muñoz’s delight, the blue wave also turned out to be something of a Latino wave: According to early voting data, Latino participation was up 174 percent compared with 2014.

Marrying architecture with activism hasn’t always made for an easy relationship, however. In the case of the Museo Alameda, Muñoz devoted considerable networking and fundraising energies before landing the commission, only to have the project lose its Smithsonian affiliation in 2012 due to financing shortfalls—a failure that many in San Antonio blamed on Muñoz himself. His tenure at the state Department of Transportation also attracted criticism for his lack of fiscal discipline, and in the world of Texas public works he is known as a hyper-competitive job-getter, with a tenacity and wiliness that more than live up to his father’s nickname.

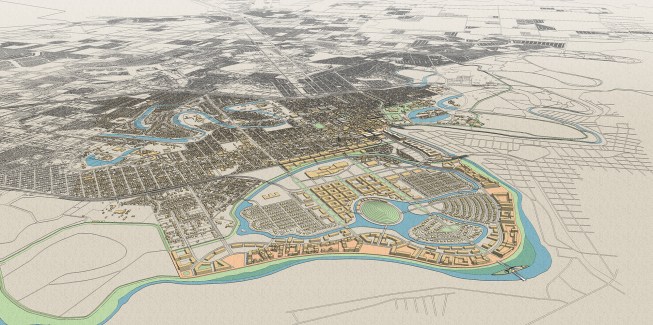

Courtesy Muñoz & Co.

Brownsville master plan

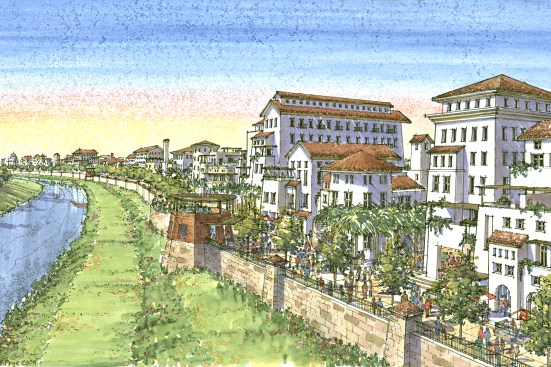

Courtesy Muñoz & Co.

Brownsville rendering

Of course, that tenacity and ambition often serve him well. In Brownsville, a border city where the U.S.-Mexico barrier fence cuts straight through the heart of downtown, the studio has been at work for years on a master plan that aims to turn a neglected segment of the Rio Grande riverbank into a vibrant mixed-use district. “We went a little bit over the top,” jokes Steve Tillotson, FAIA, who led the project. Envisioning a grand esplanade that would incorporate both the border fence and the river levee, the team proposed a dense cluster of buildings recalling a supersized Southwest adobe city, looming romantically over the riverside. As far-fetched as the proposal seemed, the rudiments of the plan are actually moving forward, with a $250 million first phase underway now.

Larry Servin

San Pedro Creek Culture Park

On the afternoon that Muñoz toured San Pedro Creek Culture Park, he strolled past new signage that explained the history of the site and its restored natural life, as well as a waterfall featuring a perforated steel panel, with star-like LEDs glowing in the exact pattern of the night sky on the date of San Antonio’s founding. Huge murals, recalling the work of Diego Rivera, covered segments of the retaining walls, recounting the story of the city’s settlement and its struggles and triumphs through the centuries. Looking at the images, Muñoz saw a reflection of his own, decidedly optimistic, outlook. “It’s all about movements of people,” said Muñoz, looking at the artwork. “And movements need architecture.”