Bags of Pozzoghana-a local variety of pozzolana ash, a concrete …

By adding Pozzoghana to portland cement before mixing the concrete used to make block and most structures, the average price of each bag of cement drops from $6 to $4, leaving the craftsmen more money for their families and making home construction more affordable. “The vision and mission of Pozzoghana Ltd. is simple: to create a complementary product to portland cement, to promote indigenous materials and know-how, and to prove that we need to look within and not without,” says Addo.

The production of Pozzoghana is undeniably a business venture for Addo and Kanner, but the partners also hope the product will have a humanitarian use. They are in talks with the Ghanaian government to use the additive to build subsidized, low-income housing in rural areas, and, Kanner reports, “They are very supportive of the product for that kind of use.”

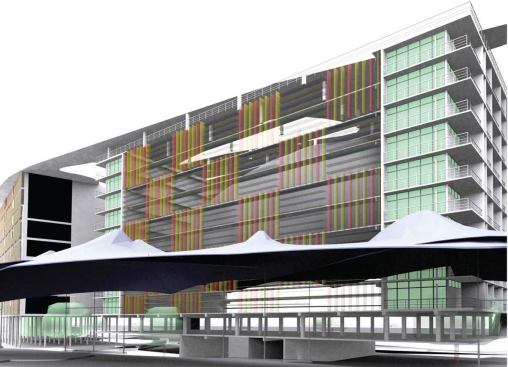

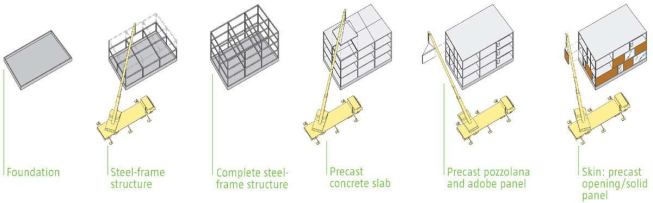

In the meantime, Kanner and Addo are already at work on three projects using the additive to showcase its versatility. One project is about to break ground: a 25-unit condominium project on Independence Avenue in the capital city of Accra, located near the airport and on a street with embassies. “The product can be used for market-rate condos as well as low-income housing,” says Kanner, “and this is just a way to have it actually in a built project, which is very exciting.” One mixed-use project using Pozzoghana has just won a competition run by a local housing developer and will break ground in the next few months, and another is on the boards. All three projects were designed in Kanner’s Los Angeles office, with Addo serving as a project architect locally. For these projects, Pozzoghana is being added to portland cement in varying ratios depending on the object; more additive can be used in decorative details than in structural slabs and columns.

Production is stepping up as well. The joint venture bought the government’s test plant, and it is now making commercial product. “If all market indicators are positive, a large-scale plant should be up in a year or so,” says Addo. More plants are in the works, with a long-term vision including many small facilities across West Africa, so that each can serve a local clientele and employ local workers. Sustainability is a major concern for the partnership. By using a renewable material and a waste product and cutting down on importing and long-distance shipping, the project can save fuel and maintain a relatively small environmental footprint.

The partners also have faith in the initiative’s financial sustainability. “Knowing Ghanaians and knowing how money is not that plentiful, I suspect that if there is a $6 bag and a $4 bag and one of them is effectively homegrown, I suspect [they] would buy the $4 bag,” says Kanner. “And I expect it will be successful because it helps their economy, it hires their people, it uses their natural resources. There are many good reasons to do this rather than import material that they have to pay more for.”

Addo feels similarly. “My interest in this project is to create a whole new industry for Ghanaians, with a product developed by us to meet our growing demand for ‘the building blocks’ for the new Ghana,” he says. “As an architect/entrepreneur, I believe that as Africans we need to control the supply chain, and I see no contradiction in my social agenda and my capitalistic endeavors—one informs and benefits the other. It’s a win-win.”