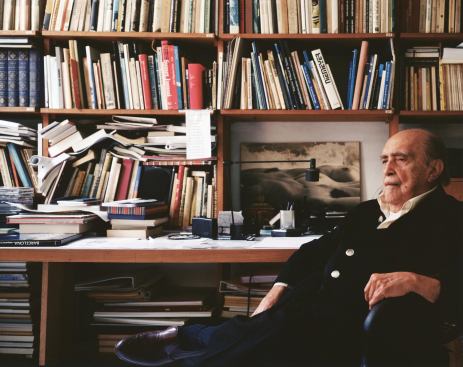

Todd Eberle

The death of Oscar Ribeiro de Almeida Niemeyer Soares Filho in D…

Niemeyer’s architecture, friendships, and lifestyle have all been held up as evidence that he was an armchair communist, tsk-tsking the status of the downtrodden while tooling around Rio in an Italian sports car. Certainly, some of his commissions seem to defy explanation—such as the Ministry of Defense—but Niemeyer’s architectural practice was not entirely in contradiction with his politics. First and foremost, there is the issue of context. Brazil in the middle decades of the 20th century was not exactly the sort of place where designers (or the government, for that matter) sat around contemplating housing solutions for the poor. A small, fair-skinned elite controlled just about everything, including half the nation’s income. Any architect who wanted to eat had no choice but to work for them.

More importantly, Niemeyer’s political views shouldn’t be held hostage to a North American understanding of communism. The Red Scare culture of the U.S. has long associated communism with the authoritarian power of the Soviet state or one of various armed movements (think: Cuba). For a whole school of Latin American leftists, however, communism—and socialism, too—are a somewhat softer concept, less about establishing a dictatorship of the proletariat than about highlighting social problems in a continent where they run rampant. (In the early 1980s, Brazil had a poverty rate of almost 50 percent. Today it stands at 21 percent—with an extreme poverty rate of 13 percent.) Nor is Latin American communism necessarily about kowtowing to the Soviets. At a 1963 speech in Moscow, Niemeyer told the assembled audience: “On the politics, I’m with you. But your architecture is awful.”

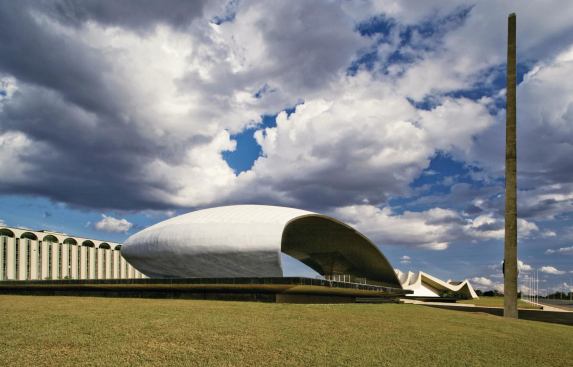

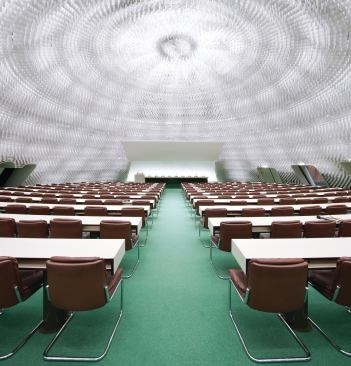

Certainly, Niemeyer’s sleek aesthetic couldn’t have been more diametrically opposed to the Soviet styles of the 1940s and ’50s. The Soviets condemned Modernism as decadent, while Niemeyer couldn’t have celebrated it more. Though the U.S.S.R. had enjoyed a short burst of avant-garde architecture in the 1920s, Stalin had put a stop to it as soon as the 1930s rolled around. The two decades that followed saw the streets of Moscow and other Soviet Bloc cities littered with a pastiche of late empire styles—Neoclassical, Gothic, and Russian baroque—all done in super-duper sizes. The numerous wedding cake buildings led Time magazine to conclude in 1958 that “Russia’s official style of architecture has long been stuck back in the Woolworth Building era.” Where Soviet buildings thrusted into the sky, full of power and might, Niemeyer’s hovered gently over the horizon. Where the Stalinists sought to intimidate the masses; Niemeyer wanted to delight them: “I try to make them beautiful and spectacular so that the poor can stop to look at them, and be touched and enthused.”

None of this is to imply that Niemeyer was buying European or American Modernism hook, line, and sinker. His buildings, in fact, embody a unique strain of 20th-century leftist thought. For centuries, Latin American elites had diligently taken their intellectual cues from Europe—in the case of architecture, reproducing baroque, Neoclassical, and Beaux-Arts designs all over their capitals. But the leftist, indigenist movements of the 20th century changed that. They championed the idea of looking inward to produce institutions that were uniquely reflective of the realities of the New World. For many prominent intellectuals—such as Chilean Nobel Laureate Pablo Neruda—communist politics were therefore about carving out a uniquely Latin American identity.

In this regard, Niemeyer’s architecture couldn’t have been more representative of leftist ideals. His buildings were singularly Brazilian in shape and form, a startling synthesis of modern principles, Portuguese design, tropical building techniques, and the undulating lines inspired by of one of the world’s great wilderness landscapes. His flagrant curves were a firm rebuff of the boxy Bauhaus Modernism emanating from Europe. “It must offer pleasure as well as practicality,” he told The Guardian in 2007. “If you only worry about function, the result stinks.”

Likewise, the construction of Brasília might have seemed like a wildly authoritarian gesture. But, for Brazil, it was also a way of shaking off the legacy of colonialism. “We must occupy our country, march to the west, turn our backs to the sea and stop staring fixedly at the ocean—as if thinking of departing,” Kubitschek declared in the late 1950s. The whole concept of Brasília, therefore, couldn’t have been more in keeping with Niemeyer’s communist sympathies. The project wasn’t simply about putting up a few grandiose buildings in the middle of the savannah, it was about rejecting northern paternalism and showing that Brazil was capable of devising its own design solutions—ones that could resonate at an international level. Decades later, in his autobiography, Niemeyer wrote, “We were beginning to show the Old World that there wasn’t much they could teach us Latin Americans.”

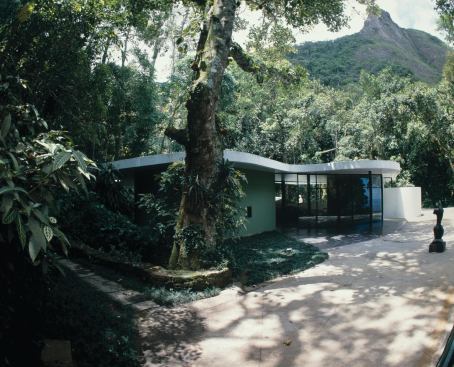

Niemeyer’s politics revealed themselves in other, smaller ways, too. His personal home, in Canoas, built in 1953, contained no separate entrance for servants, a scandalously egalitarian flourish for the Brazil of the period. In the late 1960s, he designed the rippling headquarters of the French Communist Party in Paris (which the right-leaning Charles de Gaulle described as “the only good thing those Commies have ever done”). Two decades later, he created a series of modular educational centers in Rio—referred to as CIEPs, for Centros Integrados de Educação Pública—geared at impoverished students. Moreover, the superblocks of Brasília were, in theory, supposed to house a wide spectrum of residents in similar apartments, so that lawyer and laborer might live side by side. (In practice, it didn’t work. Government cronies occupied the superblocks; the poor were left to inhabit the slums that circled the city. This, however, was hardly Niemeyer’s fault.) There are other scattered examples of his political leanings, including a series of ponderous public monuments, such as Mão, in São Paulo, which shows the bleeding silhouette of Latin America carved into the palm of a splayed concrete hand. (Subtle, it’s not.)

As has been repeatedly noted, Niemeyer produced only a modest number of socially driven projects. He explained this by saying that it was “not with architecture that one can disseminate any political ideology.” That’s a convenient position for a designer who was himself a comfortable member of the bourgeoisie. But that doesn’t mean that his politics weren’t reflected in his work. Underwood, who has written several books on the architect and interviewed him on numerous occasions, describes him as an “aesthetic communist”—someone who never called for an armed uprising, but whose designs nonetheless embody a firm resistance to Eurocentric ideals.

At the dawn of the 20th century, when Niemeyer was born, Brazil was largely an agrarian state. Today, it is a supercharged BRIC economy, producing airplanes and automobiles—not to mention plenty of architecture, from soccer stadiums to hospitals to glitzy shopping centers. Fifty percent of its population is middle class. In the next three years, the country will host an Olympics and a World Cup. Interestingly, its last two presidents have been socialist, albeit of the distinctly Latin American, market-friendly variety.

This Brazil is built, in part, on the image crafted by Niemeyer more than half a century ago. In his architecture, Latin America was finally able to see itself—in “all its grandeur and its poverty,” as he once wrote. In its time, few ideas could have been more radical.