Getty Images

Under the Poor Laws in England and Wales, the infirm elderly are…

Kwan Henmi Architecture/Planning and consulting firm Fougeron Architecture teamed up to create Parkview Terrace, which opened this summer. Principal Anne Fougeron says the designers wanted the infill building to be in context, but also hoped to update the classic building typology in San Francisco, which often includes a bay window. The answer is a faceted exterior of concrete and large glass windows that flood the modest-sized units with light (all those floor-to-ceiling windows incorporate special hardware for ease of opening by seniors). Forty percent of the units are handicapped accessible, and the rest are adaptable as residents age. An interior courtyard is situated southwest to maximize sunshine and minimize exposure to San Francisco’s famously cold fog. A community center on the street level opens to the street through a wall of glass.

“We really wanted to encourage people to be able to see in and out,” Fougeron says. “It’s the idea of being a part of the community, and not like you’ve been put away for life.”

The CCRC Alternatives: Small Centers, Green Houses, and Beyond While strides have been made, Joyce Polhamus, a vice president of SmithGroup in San Francisco and a member of the AIA Design for Aging Advisory Group, believes much more needs to be done. Polhamus advocates alternatives to the large CCRC and nursing home models, such as smaller, diversified housing options. “Senior housing design is stale as an architecture type,” she says.

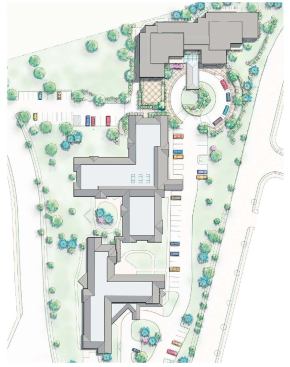

Polhamus designed an award-winning assisted living center for the Motion Picture Association of America that opened in Woodland Hills, Calif., in 2004. The building resembles a classic California courtyard house, with single-loaded corridors and expanses of glass opening onto plenty of outdoor space. “Pretty soon there is going to be the next generation that’s going to want more,” Polhamus says of the coming market demand. “They’re going to want variety architecturally and more connection to the outdoors.”

Polhamus points to the Green House concept as a good example of the coming culture change. The Green House is the brainchild of William Thomas, a Harvard-trained physician specializing in geriatric care. Thomas had an epiphany early in his career, after taking a part-time job in a nursing home. He realized that the key variable in his patients’ health wasn’t their medical treatment—it was their surroundings. His model is designed to house six to ten elders, each in a private room with bath. Every home must contain a few key elements—a communal kitchen where elders and caretakers share meals, a hearth area with an open living room, vibrant outdoor space, and lots of windows—but from there, the design is adaptable by architects to any setting. It is, Thomas says, the anti-nursing home.

“Nursing homes were designed as if relationships don’t matter, and Green Houses are designed as if relationships are the key to the quality of life,” he says. “Good design is driven by a mental map that [answers], ‘What is this place?’ We’ve designed and built 16,000 nursing homes where the medical map says, ‘This is a place for sick, frail, disabled old people to be tended to until they die.’ “

The first Green House opened in Tupelo, Miss., in 2003, and post-occupancy studies show favorable results for residents and caretakers alike. There are currently 25 projects in operation or in development in more than 20 states, and architecture firms are playing an important role in designing these spaces.

When it opens next year, the Leonard Florence Center for Living, designed by Boston’s DiMella Shaffer, will become the country’s first Green House community in an urban setting. Ten “houses” with a total of 100 residents will compose a six-story building in Chelsea, Mass. “Baby boomers are aging, and there’s a pervasive interest in wellness and fitness,” says Diane Dooley, principal architect and practice leader for senior living projects. “We are seeing more interest in senior living communities in urban environments, and in environments that provide skilled nursing-level care in houses?not just homelike, but environments that are houses.”

NCB Capital Impact has partnered with the AIA’s Design for Aging Knowledge Community on a charrette for new designs of Green Houses. As of the registration deadline in July, 75 entrants had responded.

Thomas has his own challenge for practicing architects. “No more nursing homes. Stop it. Do not design another one.”

“The conventional response would be: What are we supposed to do?” he acknowledges. “Either you have a client who wants another damn nursing home, or you have your own concerns about costs, regulations, all these sorts of things. I would argue that now, today, design in long-term care is the most exciting part of healthcare design. This is where the action is.”

And a brief history … 1500s

Under the Poor Laws in England and Wales, the infirm elderly are classed as “the impotent poor,” and some are housed in almshouses or poorhouses.

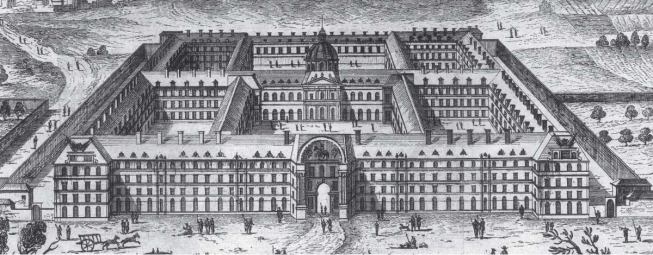

1600s

Les Invalides in Paris and the Christopher Wren-designed Royal Hospital Chelsea (1681) in London are established to care for old and injured soldiers.

1700s-1800s

Many elderly people are housed in workhouses or poorhouses, often together with criminals, orphans, and the mentally ill.

1828

As conditions in the poorhouses come under scrutiny, New York City erects separate facilities to house criminals, the ill, and the elderly.

1889

Institutionalization of elderly care has become the norm. The William Enston Home in Charleston, S.C., is an early model for a planned retirement community.

1935

The Social Security Act establishes cash payments for the elderly, helping give rise to the for-profit nursing home.

1946

The Hill-Burton Act institutes national guidelines for healthcare, ushering in the era of the nursing home as hospital.

1950

FHA and other government-backed loans spur a surge in private nursing home development. Despite basic licensing of facilities, oversight can be spotty, and conditions inside many homes are poor.

1961

At the first-ever White House Conference on Aging, the AARP unveils Freedom House.

1990

CCRCs gain in popularity-jumping from 800 at the beginning of the decade to around 2,000 today.

2003

The first Green House opens in Tupelo, Miss.

2008

AARP develops Andrus House, a contemporary model of universal design, in Washington, D.C.