Getty Images

Under the Poor Laws in England and Wales, the infirm elderly are…

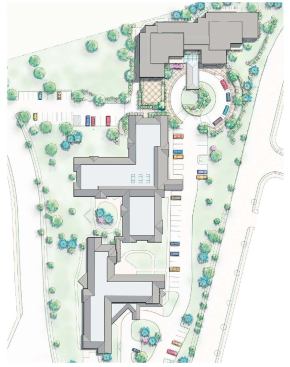

Being social creatures, what most humans want is interaction. Because isolation is a major problem for senior well-being, some developers are looking to expand the traditional CCRC into a more vibrant, mixed-use, mixed-age community. For the Newbridge on the Charles development in Dedham, Mass., Perkins Eastman is collaborating with Cambridge, Mass.-based Chan Krieger Sieniewicz to design an intergenerational campus on 152 acres along the Charles River. There will be a mix of housing options for seniors as well as a 100-pupil day care center, a Jewish K-8 day school, a summer camp, and a Jewish community center. A handful of mixed-use projects like this one are in the planning stages around the country, and architects are finding themselves in the role of master planner. “It’s very complex, but that’s the way this is going, so buckle up,” Dillard says.

Urbanization: Going Vertical Developing a mixed-use, multigenerational campus like Newbridge requires a very expensive commodity: land. Which is why, more and more, architects are designing senior housing into the existing fabric of urban centers where support services already exist. “There is an undeniable trend of urbanization of senior communities,” says Dillard. “We have several on our boards right now.” These include a contemporary tower near the Louis Kahn-designed Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas.

As senior housing moves into the city, it’s going vertical. Ankrom Moisan Associated Architects recently broke ground for the Mirabella, a 30-story, 224-unit tower in Portland, Ore., which is on track to become the nation’s first LEED Platinum CCRC. The sleek high-rise is in the city’s developing South Waterfront District and will be fully integrated into the transit-oriented, mixed-use neighborhood.

Going vertical has distinct advantages. At the Mirabella, with just eight units per floor, residents are within a short walk of elevators and have easy access to amenities like retail, health services, and classroom space; a fifth-floor garden; a 24th-floor dining lounge; and a 25th-floor observation deck. There’s also a health spa with a lap pool. Half a million dollars of fiber optics assures that current and future technological needs can easily be met.

The slim tower was designed to maintain sight lines to the nearby Willamette River, while exterior landscaping connects the building to the neighborhood. An outdoor courtyard extends into a public park across the street. Wide sidewalks will encourage pedestrian activity, and a café on the ground floor will invite the public inside (residents who are too frail to go downstairs can still get outdoors by riding the elevator to the fifth-floor garden). The LEED Platinum Oregon Health & Science University Center for Health & Healing, which includes a research center on elder care, is nearby. Because of its proximity to public transit, Mirabella has limited parking; there are, however, 61 bicycle spaces and 20 spots for kayaks.

“This is all about quality of life,” says Jeff Los, a principal at Ankrom Moisan. “Every decision is focused on how to maintain the optimum experience for the individual, on how to keep people connected to the city.”

The South Waterfront development the Mirabella belongs to requires that every building in the district achieve at least LEED Silver; when it is complete, it will be the largest green community in the country. Los found that going platinum was financially beneficial for his client, Pacific Retirement Services. “I teamed up with the accountant at Pacific, and we realized that we saved $3 million at the outset,” Los says about the energy savings. “It turned out that LEED was an economic benefit.” (Changing to variable-speed motors on the HVAC system, for example, cost $58,000, but the switch will save about $42,000 a year in energy costs.)

The future residents of Mirabella are, according to Los, movers and shakers. “The big change that I’ve seen over my 30-year career is that older people control a very high percentage of the financial resources in the country, so they have a lot more money to spend than my parents did,” he says. “Most of the people moving into Mirabella are former bank presidents and community leaders. I doubt there are any architects, because we can’t afford it.”

Which raises an important question: What if you can’t afford this new luxury? As in all areas of U.S. housing, affordability for seniors is a major issue. AARP says entry fees to CCRCs range from $20,000 to $400,000, with monthly payments as high as $2,500 per person. At the Mirabella in Portland, entry fees can be as high as $700,000, with monthly fees for services ranging from $2,500 to $4,500 a month, according to Los.

In San Francisco, several new projects aim to give seniors affordable options. The demolition of the city’s Central Highway in the mid-1990s freed up space in a neighborhood previously bifurcated by the road. The city issued an RFP for an affordable senior housing development with 101 units and a percentage of apartments set aside for the homeless.