Tim Maloney

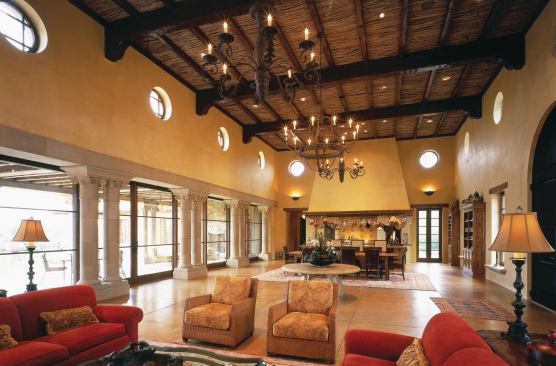

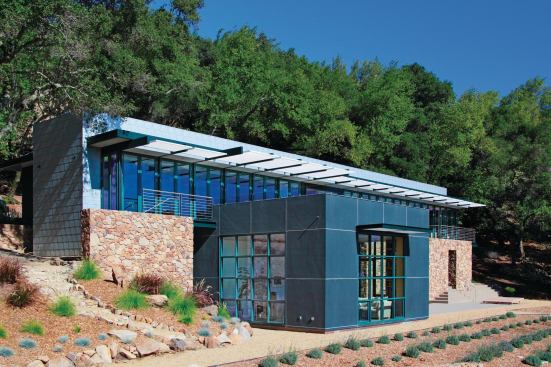

This California home's stone-and-plaster walls conceal a high pe…

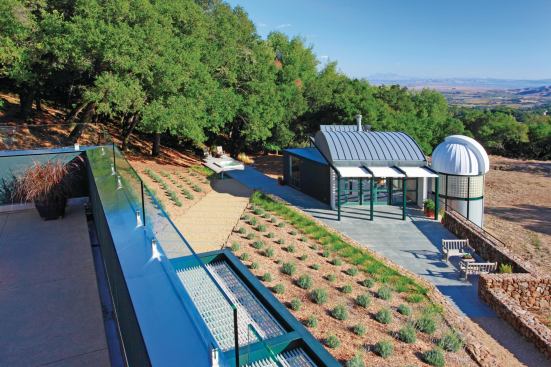

Lead superintendent Larry Braughton meets Murphy at the sun-baked clearing of the guest house site. Sun-baked himself—the dry season has been unusually hot this year—Braughton started with JMA 22 years ago, as a finish carpenter. “This is the first time we’ve had three of us on the site full time to keep track of everything,” he says. “We’re going to have five buildings going all at once.” Asked if the project ever keeps him up at night, Braughton laughs, “It keeps me up all nights. Two o’clock in the morning, that switch goes on.” One thing he doesn’t worry about, however, is ever getting in trouble for going the extra mile for the client. “I don’t have to ask if I can do it. [Murphy and True] want it to be there. They want things done the right way. That makes them happy, and it makes my owners happy.”

No Accident

Construction has always been a dangerous business, but the issue became personal for Jim Murphy and Jay True when one of their carpenters took a bad fall. “I spent about six hours with his wife at the hospital,” remembers Murphy grimly. “It was about a year before he came back to work.” The accident “terrified us,” says True, but the partners channeled their shock into an effective focus on safety that their company, Jim Murphy & Associates (JMA), has sustained to this day.

JMA conducts regular safety inspections, holds safety demonstrations at its regular staff meetings, invests generously in safety equipment and training, and will have a subcontractor employee pulled from a job for failing to comply with safety procedures. Thrice-yearly company picnics include job site “vignettes,” where employee teams win prizes by flagging the most safety violations. Employees earn a $50 gift card for each quarter completed without an accident; if the entire company is accident free, the award is doubled.

More important than any one program, however, is the pervasive message that safety is a priority. Over the years, JMA has employed varying tactics to teach and promote safety. “There’s always been an attenuation effect,” True says. “What we’ve found most important is just constantly reinforcing that Jim and I really care.” The formula is working. In 2009, JMA won an NAHB Safety Award for Excellence. Better than that, True says, “We’ve just had our fourth [insurance] policy year without an accident.”

Back at JMA headquarters, a well-kept but nondescript building near the freeway in Santa Rosa, True describes what it takes to maintain control of both product quality and client experience at this altitude. “Your challenges grow geometrically as your payroll grows,” he explains. JMA has grown at an average annual rate of 15 percent, “So we’ve had to get more systematized, more sophisticated.” Three times from the early 1990s to 2005, the company retained management consulting firm FMI to help update its structure, systems, and procedures. “The first came at around $5 million to $8 million in volume,” True says. “At that point, Jim and I still had our hands in everything; one of us knew every job. We had to make a deliberate attempt to let go. Not just to respect the people we had working for us, but actually to give them some rope.” At that stage, the partners wrote formal job descriptions and established regular project manager meetings and a separate, monthly meeting for project managers and superintendents.

“The next hurdle was when we broke $12 million to $15 million,” True continues, a point at which the company needed to document its operating system. “We had to create process maps,” he says. “I had a schematic process model, but it wasn’t really integrated into one big whole.” True codified company procedures in a manual titled “An Employee’s Guide to the Way Things are Supposed to Work,” which remains holy writ on matters ranging from hiring, salaries, and benefits, to estimating, billing, and the company’s safety program (see “No Accident” sidebar) .

By 2005, he says, “we were breaking $30 million to $40 million, and we had to start acting like a big-time contractor. We decided to become more strategic about our future. We needed a farm system.” To recruit talent, the company now seeks interns from colleges with construction management programs. A relatively new position, assistant project manager, supports the company’s ever-larger projects and serves as a stepping stone for the next generation of project managers. Murphy and True invite employees to audit client and subcontractor meetings that are, technically, above their pay grade, then conduct post-mortems to determine what they’ve learned about the company ethos.

Through three decades of growth and change, that ethos seems to have remained remarkably constant. For that, True credits his partner. “If there’s management and leadership,” he says, “I’m management, and Jim’s leadership.” Project manager Quesenbury concurs. “Jim’s kind of a bigger-than-life person,” he says. Once a competitive amateur tennis player, Murphy now spends his weekends building and racing 4,000-horsepower top fuel dragsters—and winning. Despite such extracurricular heroics, though, Murphy’s influence derives much more from his approach to his work, and from a moral code that places equal value on excellence and fair dealing. “You see how hard he’s working to make it right,” True says, “and you don’t want to let him down. It’s leadership by example. You see it in everything he does, so you think, ‘This must be the standard.’”

Murphy is not a big talker, but he makes every word count, and his employees collect and repeat his sayings like Zen koans. On job sites, they wear T-shirts emblazoned with the words “Murphy’s Law,” followed by a quotation: “On a JMA job, perfect is barely good enough,” “If it isn’t fair, it isn’t right,” “The more you plan at the start, the less you fix in the end,” “Monsters in the closet never get smaller. Deal with them now,” or “We work with people we can trust, and they have come to trust us.” It is worth noting that these are not slogans aimed at marketing the company; they are a means of building character and spreading wisdom within the company. Character and wisdom take time to develop, and JMA has had more than three decades to build up its store of both. But in business leadership, as in wine, age does not always yield excellence. Oenophiles speak, instead, of “maturity,” the point at which a wine reaches its full potential. In the field of custom building, Jim Murphy, Jay True, and their company do more than exemplify maturity; they define it.