Tim Maloney

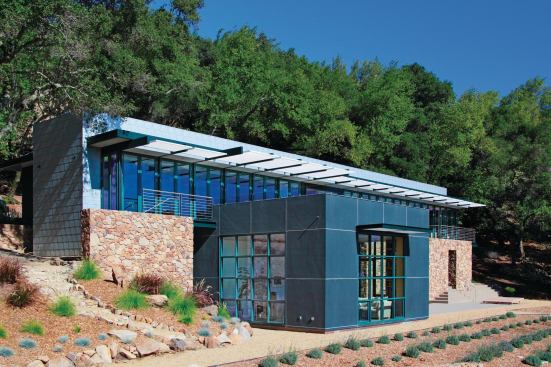

This California home's stone-and-plaster walls conceal a high pe…

True, now 59, entered the picture in 1983. An engineer by training, he had attended Stanford University—with some help from ROTC—and spent two years in a Navy construction battalion, building recreation centers and ball fields. “It was fun,” he remembers. “It was like contracting, but without the risk and with no budgetary problems.” When he and Murphy met, he was a contract administrator for a large commercial construction company. Murphy says, “I would bug Jay for subs or ideas.” True joined the company in 1987, but not as an employee. “Jim insisted that we be 50/50 partners,” True says, “and that was pretty cool, to me. I had no ambition that that would be the way I’d start.”

True expanded the company’s capabilities in important ways. “We realized that by bringing the systems approach that I had to residential and bringing Jim’s talent for quality to commercial, we could stand out in both venues,” he explains. “It was kind of a yin-and-yang thing: Jim was the craftsman; I knew how to make the numbers add up.” Not that Murphy was out of touch with the books, however. “It was uncanny to me,” True recalls. “He knew the balance in our checkbook to within a couple of dollars. And I signed all the checks. He had been able to run the business completely in his head.”

At 6 feet 6 inches, True is 2 inches taller his partner, but he spends a lot more time hunched over a desk. Murphy says, “Jay calls himself the vice president in charge of paperwork.” Be that as it may, one of his first initiatives was to lead JMA out of the paper age, computerizing its accounting, scheduling, and project management. “Today,” True explains, “the custom builders in the market we’re in are pretty sophisticated.” But with the “shoebox” accounting typical 20 years ago, “the choice was either time-and-materials forever or a fixed price contract.” True’s commercial-grade systems afforded much closer cost control. “That allowed us to offer a guaranteed maximum price contract to our residential clients,” he says. JMA runs the majority of its projects on this model, which offers clients the best features of cost-plus and fixed-price contracts—and the potential to get money back at the end of the job.

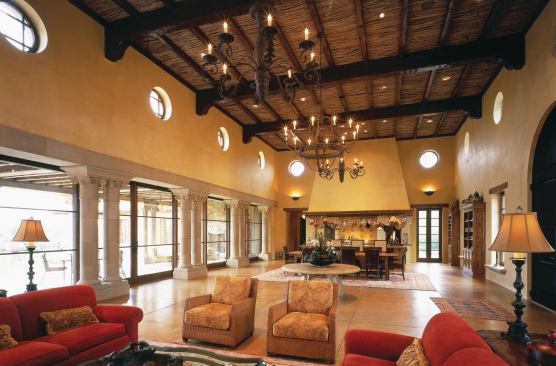

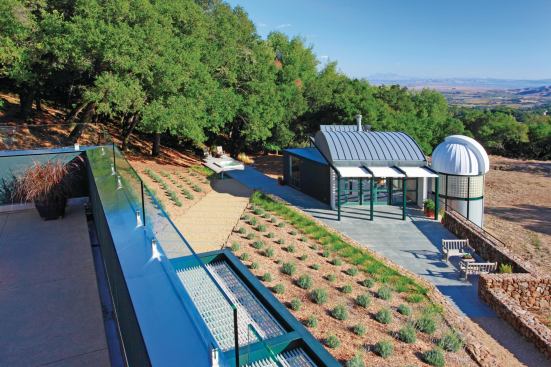

The new partnership expanded the company’s reach in commercial work and streamlined its residential operation. It also opened a new market in projects that require expertise in both disciplines, such as resorts and schools. Wineries, which often include industrial, retail, hospitality, and residential functions, have become a company specialty. But JMA’s stock in trade soon became houses that apply design and finish of the highest order, sometimes at a scale—and with systems—more common in commercial buildings. Here in the wine country, it is a segment of the business where standards of scope and technical difficulty are still on the rise. A JMA project under way in upper Napa Valley represents the current high-water mark.

Murphy lowers the window of his Acura SUV and taps an electronic key pad. The gate swings open, and he eases down a long dirt drive. To the left, earthwork contractors have scraped a 13,400-square-foot pad for the barn that will house the owner’s collection of exotic cars. Ahead, the drive climbs steeply to a leveled shelf on the hillside, where a pair of guest houses will open onto a swimming pool. Higher still, perhaps 120 feet above the car barn, foundation work is under way for the main house, a 12,000-square-foot farmhouse-style structure that will surmount the property like a medieval castle. “We’re on 62 acres, and yet we’re building everything in these little shoebox areas,” observes Murphy, perfectly unperturbed. “We can’t get to the back of anything; we’re constantly building from the front and backing out.” The foundation crew has already poured a 15-foot-by-18-foot concrete planter box for a huge native oak that will rise through the main deck, one of several in the plan. “They’ll come with a 12-by-12 root ball, 40,000 pounds, each tree,” he says. “They’ll bring them on a Cozad trailer, and it will take a 200-ton crane to set them. We’ll be using 150 tons of counterweight, which will give us a swing radius of 40 feet. It’s pretty fun.”

There’s plenty of fun to go around. With more than 30,000 square feet of buildings—including a caretaker’s house and a fire-pump house—the job will occupy two project managers, a project engineer, two full-time superintendents, and a foreman whose primary job will be to verify dimensions on framing and finishes. Project manager Michael Quesenbury says local code officials have informed him that this is the largest construction project under way in Napa County—commercial or residential. The delivery of a 45,000-gallon water tank required a California Highway Patrol escort. (The 12-foot-by-61-foot tank, now buried, is primarily for firefighting; two 10,000-gallon tanks will store domestic and irrigation water.) The site work will require permits from both the California Department of Fish and Game and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. In terms of utilities and permitting, “It’s like a subdivision,” Quesenbury says. When the last JMA truck pulls out, though, the atmosphere will be more like that of a bucolic ranch—albeit one with a high-resolution, fiber optic–linked surveillance system capable of license plate detection at 100 mph.