The two architects stand amid newly planted trees in a stormwate…

As effective models for aggressive job creation, the framework cites organizations such as TechTown, a local nonprofit that incubates more than 250 research and technology businesses. Since 2007, TechTown has created 1,085 jobs and has partnered with a community organization in Brightmoor, a struggling neighborhood, to provide business support to area entrepreneurs.

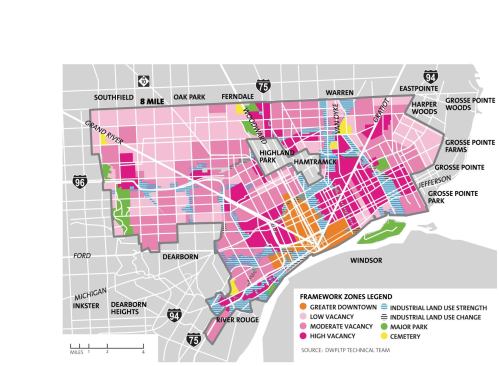

The framework advises targeting industry for growth, as well as the creative economy, eds-and-meds, and entrepreneurship in a variety of sectors. Ubiquitous images of vacant factories notwithstanding, Detroit Works documents how city businesses that process, manufacture, repair, and distribute physical goods employ 27,000 people. The framework suggests more investment—particularly in the Eastern Market, Mt. Elliott, and Southwest neighborhoods, where industry will be supported by access to an airport, freight lines, highways, waterways, and the international border with Windsor, Ontario, Canada.

The framework details 11 other imperatives in addition to economic growth, including promoting a range of sustainable residential densities and attracting new residents to the city. It maps community assets (such as historic districts and libraries) and identifies strategies to bolster already-strong neighborhoods and make productive use of vacant land in low-occupancy neighborhoods (an effort that would be aided by better coordinating the city agencies responsible for land use). Prioritize stabilization of neighborhoods within a half-mile of schools, the framework advises. Target absentee landlords and owners with code enforcement programs. Incentivize multifamily housing.

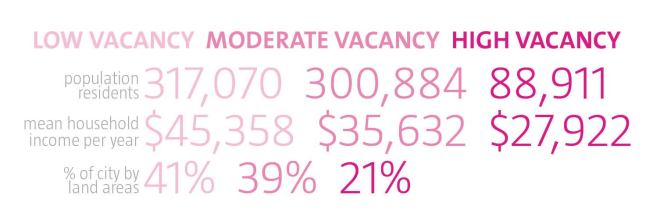

One unexpected detail from the Detroit Works research: Only 88,911 residents live in high-vacancy neighborhoods, compared to the nearly 619,000 in more stable areas. But high-vacancy areas make up 21 percent of the city’s footprint. It’s a cruel triptych: a glut of single-family homes, low market demand, and buildings that become more dangerous the longer they’re vacant. For immediate support of high-vacancy areas, the framework suggests boosting resources for existing community patrols, revising zoning to allow a wider spectrum of land uses, and constructing a citywide network of greenways and bike lanes.

But the larger goal is to turn land and properties over to productive uses. Detroit Works spotlights reimagined spaces such as urban farms (large and small, commercial and community) and the Power House project led by Design 99, a local design firm that turned a foreclosed house into an off-the-grid power production facility fueling a new artist colony.

Forced relocation is off the table, though incentives may not be. When a woman at a community conversation asked how Detroit Works intended to get past what she portrayed as the stubborn stance of residents who “have this attitude of ‘I’m not moving,’ ” Kinkead replied, “We don’t need to move [people] … There are a series of options, from moving the house to land swapping to remaining [in the house], but disconnected from some systems—not with less services but with different services, like a rural environment. People can remain and still be part of the infrastructure.”

By providing multiple, simultaneous views of the city, Detroit Works will help leaders make decisions that don’t work at cross-purposes with others. For example, Detroit Public Schools administrators may need to close schools in areas with fewer children. But if they see momentum in Neighborhood A—perhaps it has amenities that appeal to families, and some commercial shops are finding success—the administrators might keep Neighborhood A’s school open and instead close Neighborhood B’s school, which, they see in the framework, is in an increasingly industrialized area.

Kinkead is especially interested in how more sensitively chosen infrastructure can interweave neighborhoods with landscape, in contrast to Detroit’s history of big infrastructure investment—namely, freeways—which he calls “devastating.”

“Now we have the opportunity to do soft infrastructure—seamless with the community,” he says. Detroit has 37 square miles of open space—more land than all of Manhattan. The framework suggests creating holistic blue and green landscape systems, adding trees and lakes with both recreational and infrastructural value. Dispersed ponds, for example, can aid stormwater management, easing the burden on city services while ensuring that residents don’t face flooded streets on rainy days.

But all of this is an idea, not an agenda. No planning trend will solve Detroit. No pet project translates into the transformation of an entire city.