Over the weekend, as thousands of people gathered in the nation’s capital to protest against racial injustice on the 57th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington, a small team of architects from SmithGroup‘s Washington D.C. office—led by principal Dayton Schroeter, AIA, and architect Julian Arrington—erected an installation called “Society’s Cage.” Located on the National Mall, just east of the Washington Monument, the 15-by-15-foot steel pavilion explores and confronts the realities of the Black experience in America, creating what Schroeter calls a “beautiful rendition of the ugliness of racism.”

Working with D.C.–based fabricators Gronning Design + Manufacturing, Silman for structural engineering, and fundraising support through the Architects Foundation, Schroeter and Arrington—along with SmithGroup architects Monteil Crawley, AIA, Ivan O’Garro, AIA, and Julieta Guillermet—designed “Society’s Cage” as a grassroots response to the killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, and as a way of expressing solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement and contributing to the national conversations on institutional racism and white supremacy. “We wanted to contextualize the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor,” Schroeter says. “We’ve been conditioned as a society to believe that the police who commit senseless murders are bad apples. We are led to believe that these shootings are anomalies. But ‘Society’s Cage’ contextualizes these murders within the 400-year history of state violence in the colonized Americas.”

Alan Karchmer Photography / Courtesy SmithGroup

“The first question that we asked ourselves is: ‘What is the value of Black life?’,” Schroeter says. To address that question, the designers began with the equitable shape of a cube, before eroding its form to evoke the relationship between Black individuals and existing systems of power until the pavilion literally took on, as Schroeter explains, “the shape of racism.” Steel bars, suggesting prison bars, form the pavilion’s walls; inside, visitors enter “The Void,” a space filled with obstacles representing those that Black Americans face daily: 484 1-inch-diameter, rusted-steel pipes of differing lengths are suspended from the cube’s steel ceiling. Each section forms physical bar graph of one of four forms of state violence: lynchings, police violence, mass incarceration, and capital punishment. The design team wanted the combined form of the bars to give shape to the realities of racism in the U.S., and to evoke a feeling of pressure on those inside the pavilion. “There’s a force, there’s a weight and oppression,” Arrington says. “There’s an oppressive force that sort of weighs down on you as an individual in the Black community in America.”

Alan Karchmer Photography / Courtesy SmithGroup

At the same time, the rusted pipes, which Arrington explains are intended to evoke the enduring legacy of institutional racism and “the idea of the weathered institution and how long it has existed and worn on the ethos and more specifically the community,” whistle and move in the wind, generating an atmospheric quality of tree branches in a forest. Schroeter explains that this is intended to remind visitors that forests were both a “sanctuary and sacred space that provided passage and refuge for the enslaved who might’ve escaped during slavery, but also a space of deep trauma and suffering as these were also spaces where the enslaved were hunted, tracked, and sometimes lynched.”

Alan Karchmer Photography / Courtesy SmithGroup

Inside the pavilion, a haunting soundscape in four parts—composed by New Orleans–based musicians Raney Antoine Jr. and Lovell “U-P” Cooper—loops on repeat; totaling 8 minutes and 46 seconds long to represent how long the Minneapolis police officers deprived George Floyd of air. Visitors are invited to hold their own breath, to consider Floyd’s experience, and to post about their experience on social media using #SocietysCage. On the pavilion’s floor, quotes about Black resilience from prominent leaders of color surround the names of 10,000 victims of racial violence.

#SocietysCage on display for all to safely experience on the mall at 12th & Madison. Powerful and chilling illustration on the past and current systemic racism in our country. @SmithGroup pic.twitter.com/f6AHtuaOyp

— Rah Foard (@rahsallthat) August 31, 2020

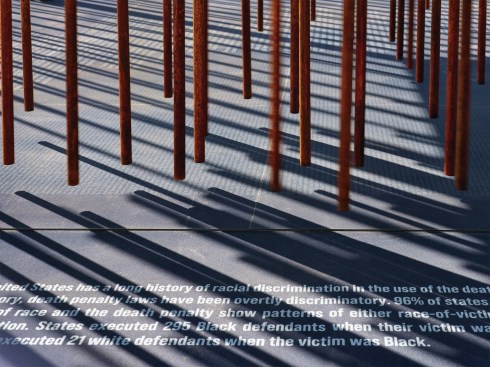

The outside of the pavilion, graphic and eye-catching even from a distance, offers just as much information as the interior. A steel apron around the base of the structure is inscribed with facts and statistics on how systemic racism creates obstacles to employment, housing, and education for Black people in the U.S. These materials, interspersed with QR codes that link to further sources, provide visitors with the chance to educate themselves. “In order for us to heal as a society and reckon with our past, we have to face our past,” Schroeter says. “We’d love to have a Kumbaya moment, but I think you have to acknowledge the past in order to get to a transparent and clear future—you can’t just skip over that step. Dealing with the truth is key.”

Once the pavilion opened to the public on Friday Aug. 28, the design team welcomed flocks of visitors moved by the pavilion’s significance. From an older white man reckoning with his complicity in systems of oppression, to a young Black man hesitant to enter the pavilion due to a history of incarceration in his family, many visitors shared their powerful reactions with the architects. “It was a reckoning for some and a moment of pause and reflection for others, but a moment of healing for everyone,” Schroeter says.

Alan Karchmer Photography / Courtesy SmithGroup

The pavilion’s current installation ends Sept. 12, and while the team does not have any immediate plans for its future, the structure is not site-specific; once dismantled, the pavilion can be rebuilt anywhere. According to Schroeter, one of this weekend’s visitors suggested the pavilion become a permanent artifact in the nearby National Museum of African American History and Culture; the team has also received interest from around the country in hosting the pavilion. But Schroeter and Arrington also explain that this single installation could also become part of a broader project: This pavilion focuses on data about the Black experience in America, but what if the same approach was applied to a series of pavilions focused on the Latino experience, the Asian experience, or the white experience? “If we have these cubes sit side by side in comparison, you could just imagine the spatial and material differences that you would get inherent in each of these pavilions based on the unique data sets that describe the group experiences,” Schroeter says.

“There’s a lot of stories that need to be told across the country—across the world really,” Arrington says. “Broadening the scope of our audience and creating other experiences to heighten the level of empathy would be very strong and powerful.”

Alan Karchmer Photography / Courtesy SmithGroup

“Society’s Cage” will be on view on the National Mall at 12th Street NW and Madison Drive NW through Sept. 12.

Note: This story has been updated since first publication.