Stadiums, aqueducts, bridges, opera houses, museums, city halls—going back to the ancients, extraordinary public building projects are the most enduring evidence of a civilization’s technological and artistic prowess, and, ineluctably, its political and cultural ambition. Today’s courthouses, schools, highways, embassies, and so on are likewise a repository of a nation’s ideals and competence at a particular moment. Only a fledgling idea three decades ago, today, architectural policies serve many countries as a powerful tool that may be put in the service of a range of functions, practical and symbolic alike.

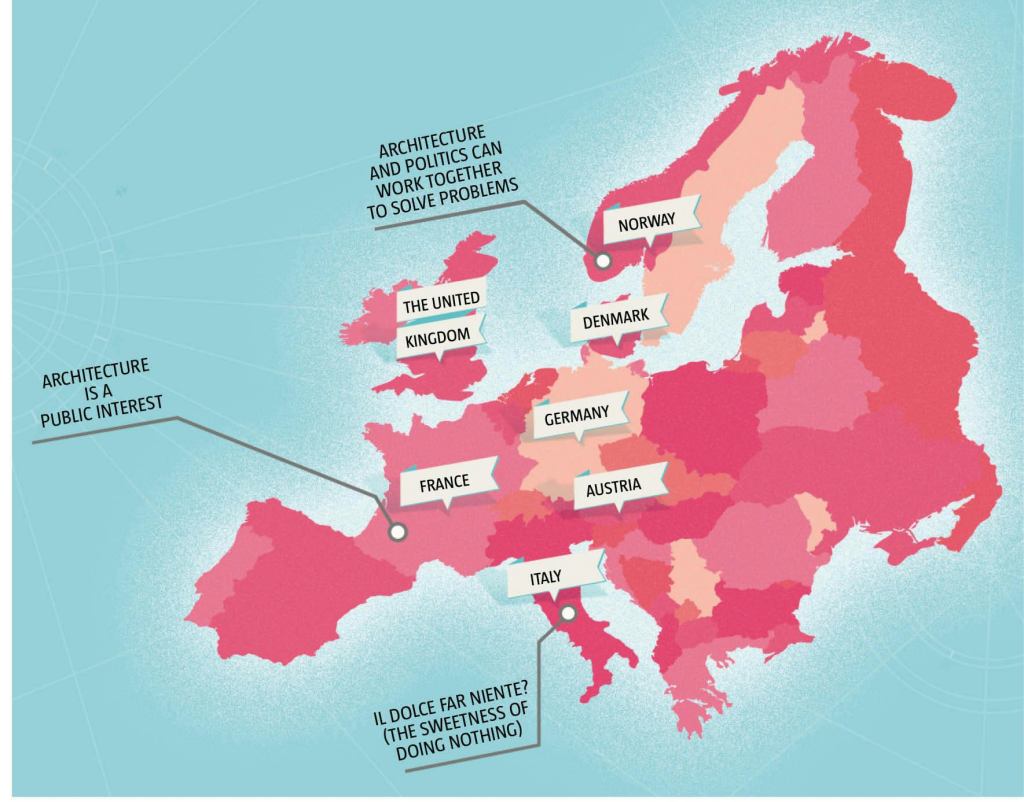

A Survey of National Architecture Policies

Austria

Austria is a federal state (like Germany), which means that its nine Bundesländer are primarily responsible for implementing architectural policies; in other words, provincial governments define their own quality standards for federally funded housing or land-use planning. At the Austrian Parliament’s request, progress in the provinces is analyzed every five years.

Denmark

In reliable Scandinavian fashion, Denmark’s policy, adopted in 2007, starts by prioritizing “quality of life”—but what’s most interesting about the policy, which was presented as a collaboration between the Ministry of Economic and Business Affairs and the Ministry of Culture, is its emphasis on architecture as it promotes tourism and global exports. The policy states, “Danish architectural businesses constitute a competitive, dynamic and globally oriented sector with documented international experience and power of penetration.”

France

The success of France’s architecture policies and initiatives owes to a comprehensive, multilayered network that works from the top down to promote the value of design in economic and cultural terms. This network encompasses dozens of councils, interministerial agencies, and other departments.

Germany

The Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Housing launched the Architecture and Baukultur Initiative in 2000. A coalition of nearly three dozen government, university, and industry affiliates—in addition to every imaginable design-related professional organization—the initiative is primarily focused on building awareness among all those involved in the building process and outlining regulations for federal procurement competitions.

Italy

The country with the world’s highest number of architects per capita, Italy drafted an architecture policy—but lacks a political champion who will back it. The government created le Direzione Generale per l’Architettura e l’Arte Contemporanee (DARC) in 2001, drawing on the French model of financing municipal competitions—a function DARC has failed to perform.

The Netherlands

This country has the interesting government post of chief architect, a position that rotates among professionals—usually an admired private practitioner, not a career bureaucrat. The chief architect’s responsibility is to “stimulate the architectural quality and urban suitability of government buildings” and to advise the government on policy as well as the selection of architects for state projects.

Norway

Norway’s policy integrates discussions about landscape architecture, open space, livable cities, cultural heritage, sustainability, and the expansion of a knowledge industry. The National Tourist Routes perhaps best exemplifies the ambition of the policy: A project of the Norwegian Public Roads Administration, the campaign to develop and improve 18 routes has led to the completion of dozens of stunning works, including observation platforms, footbridges, and kiosks by emerging architects and landscape architects.

United Kingdom

The Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) is often held up as a model that lifts design standards in the development of buildings and public spaces. Since its founding in 1999, CABE—which became a part of the Design Council as of April 1—has conducted over 3,000 reviews of major developments, offering independent critical and technical advice.

USA

The U.S. has enacted more design initiatives than most people are aware of—with particular landmarks occurring during the presidencies of Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Reagan, and Clinton, including the establishment of the National Endowment for the Arts, the Federal Design Improvement Program, and the Presidential Design Awards.

France, the Netherlands, Finland, Germany, Denmark, and Norway are just a handful of the two dozen or so countries—located primarily in Europe—that have introduced robust national architecture policies, state-funded initiatives, or government agencies dedicated to advancing design excellence in the public realm. The idea is only gaining momentum. The Brussels-based European Forum for Architectural Policies (FEPA), established in 1997, compiles best practices, convenes officials, and shares knowledge on how nations may best formulate and implement their own policies or systems. In Europe, a national architectural policy is becoming as standard as, say, adopting a national policy on climate, energy, or housing.

And it makes sense. Why shouldn’t all developed nations articulate a position on a field that impacts everything from resource consumption to urban development, public safety to economic growth?

France’s system is the oldest and, in many respects, the most successful, proving that government-backed efforts can not only elevate the quality of civic construction but also embed an attitude among politicians and the general population that design is intertwined with myriad matters of national concern.

The defining moment for France’s architecture policy came in 1977 with a law that declared architecture “un intérêt public,” officially rendering it a social issue and thus the government’s responsibility to defend and promote. This law brought about the creation of the Conseil d’Architecture, d’Urbanisme et de l’Environnement (CAUE), with offices across France’s 91 administrative departments advising local officials, developers, and citizens on construction projects and competitions.

Norway’s national architecture policy, adopted in 2009, is among the most recent. It is also impressively far-reaching, drafted with the participation of 13 of its 18 ministries (ranging from the ministries of Defense to Children and Equality). The 100-plus-page document pointedly regards architecture as an apparatus to improve society, safeguard culture, and stimulate the economy.

Highlighting three major priorities—sustainability, urban and social transformation, and knowledge and innovation—the policy begins with the position that the government should act as a role model and ends with the goal of increasing the visibility of Norwegian architecture internationally. “It’s not just about promoting architecture but about seeing how architecture and politics can work together to solve problems,” says Lotte Grepp Knutsen, state secretary in the Ministry of Culture.

With one major exception, developed nations have increasingly adopted centralized policies on architecture over the past two decades. Would such action—whether a policy, a federal agency or commission, executive order or some other central effort—be feasible in the United States?

The U.S. government, in its own way, has promoted architecture and design excellence throughout its history: Thomas Jefferson, himself a noteworthy designer, was the earliest proponent of the idea that architecture could play a significant role in the important task of national growth and accretion—then, a very pressing concern for the former colonies. A look at the country’s built legacy shows impressive design high points, from City Beautiful urban plans to major infrastructure projects to a vast array of exemplary federally funded buildings, memorials, and monuments.

The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA, founded under President Johnson in 1965) and the General Services Administration’s Design Excellence Program (launched in 1994 during the Clinton administration) are the most directly engaged in promoting design at the highest level, though the government’s efforts are channeled on multiple fronts, including the National Endowment for the Humanities, the President’s Committee on the Arts and the Humanities, the Smithsonian, and the State Department (which oversees the country’s representation at international expositions and the construction of overseas embassies and residences).

The support is clearly there, but the efforts are dispersed and thus don’t register as powerfully as they might with respect to nurturing an awareness among government agencies and the general public of the importance of design to our culture—and also the economy. This might explain why last August the NEA and GSA jointly issued a request for proposals (RFP) for “the research, analysis, and planning of a new design initiative.”