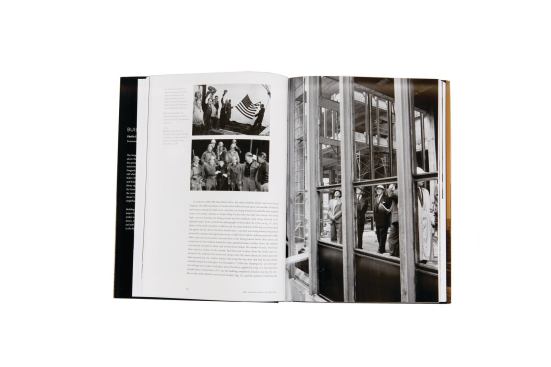

Building Seagram

Philip Johnson, Ludwig Mies van Der Rohe, and Phyllis Lambert di…

But the true value of the book lies elsewhere—namely, the degree to which it is a study of architectural patronage, one of the most underexplored topics in the profession. Architects and critics alike talk all the time about how the best buildings in any firm’s portfolio can be traced back to a productive, if not always placid, relationship between architect and client. And plenty has been written about the personalities—typically oversized—of the great impresarios and patrons in architectural history, from the Medicis to a contemporary figure like Thomas Krens, who helped make the Guggenheim Museum synonymous with globe-hopping architectural ambition.

When it comes to the science and psychology of patronage, though, to dissecting the particulars of the give and take between architect and client that has produced our most important landmarks, the record is remarkably thin. Lambert’s, in fact, is one of the few scholarly books I know of that is written from the client’s point of view.

We should always be careful not to suggest that a simple equation—smart client plus brilliant architect equals great building—controls this process. As Lambert makes clear in Building Seagram, many top executives in the company, not just her or her father, played key roles in shaping the design of the building; and she is at pains to document the precise nature of Johnson’s contributions, along with those of the lighting designer Richard Kelly. Architecture firms and corporations are both many-headed beasts, and it’s in the sometimes unwieldy struggle between those beasts that architecture is created.

Lambert, for her part, is never quite able to commit to calling herself the single or lead client for the Seagram building; the closest she comes is to qualify the word by putting it inside quotation marks, describing her role as “identifying the architect [and] serving as director of planning and, in effect, as ‘client.’ ”

But in other ways she is quite clear about her role. For her father, she writes, “The Seagram Building was to be more than a company headquarters: I believe he came to see it as a monument to … his company, which was his own doing, and therefore, ultimately, a monument to himself. But these desires were latent and needed to be articulated.”

In the end, she writes, “I was able to catalyze my father’s vision.” I think she could have done without the quotation marks in describing her role as client, as the book is one long and generally persuasive argument about the centrality of the part she played.

And it raises an obvious question: Where are the other books on architects and their patrons, the studies of how clients can ruin or improve a firm’s work? The need for such titles seems obvious, especially in an age when leading architects are so globally prolific, and when the quality of their massive output varies so widely.