Landmark opened two additional cinemas last year in Denver and Baltimore, each with similar boutique design elements. At all three, high-end concession stands that carry gourmet or regional fare—you can get crabcakes in Baltimore—promise to grow Landmark’s concession-based revenue (across the industry, movie concession stands generate $3.5 billion a year). Landmark will further expand its food offerings with a new restaurant at the flagship, scheduled to open in September. Dallas-based Consilient Restaurants has entered into a partnership with Wagner/Cuban Cos., Landmark’s owner, to create a $5 million, 10,000-square-foot bistro on the mall’s street level. PleskowRael will again work with interior designer Dana Foley on the project, tying it aesthetically to the cinema above.

THE NEW MOVIE PALACE

Development Design Group (DDG) in Baltimore has been the exclusive architecture firm for Muvico Entertainment since 1997. DDG helped the Florida-based Muvico build a brand identity through a series of themed theaters with over-the-top designs on an amusement-park scale. Muvico has “ancient Egyptian” theaters in Florida and Maryland and one scheduled to open later this year in New Jersey. Other Muvico themes include a Beaux-Arts “Paris opera house” and a 1950s “drive-in” theater.

“The question I’m often asked by other architects is, ‘Is this architecture?’ ” admits Roy Higgs, CEO of DDG. “I call it ‘entertainment architecture.’ At the end of the day, you have to create something seriously entertaining. The design detail that goes into this is extraordinary, and the cost to build one of these is not inexpensive.” The average cost of a themed Muvico cinema is about $30 million.

Muvico’s investment is paying off. Today, the company has 259 screens in 14 locations around the country; several of its theaters rank in the top 100 for box-office revenue, including the 24-screen Egyptian megaplex at the Arundel Mills mall in Maryland, the highest-attended cinema in North America. “In 2003, Arundel Mills attracted close to 3 million people,” says DDG vice president James Andreone, who helms the Muvico design team. “Just by comparison, Camden Yards, where the [Baltimore] Orioles play, was getting about 1.5 million that year.”

In addition to eye-popping design, Muvico offers supervised childcare, making it easier for mom and dad to make a spontaneous trip to the movies, and, for an extra cost, a “premiere” experience that includes valet parking, reserved seating, and free concessions.

Yet in spite of the continued success of theaters like the Egyptian, Muvico is now heading in a different direction. “We think there’s a shift in the industry,” says Mike Wilson, a senior vice president of Muvico. “It’s becoming more sophisticated.” Movie distribution is also having an effect, Wilson says: “The window between the theatrical release and the DVD release is shortening. To capture and maintain the audience, we need to create a better experience.”

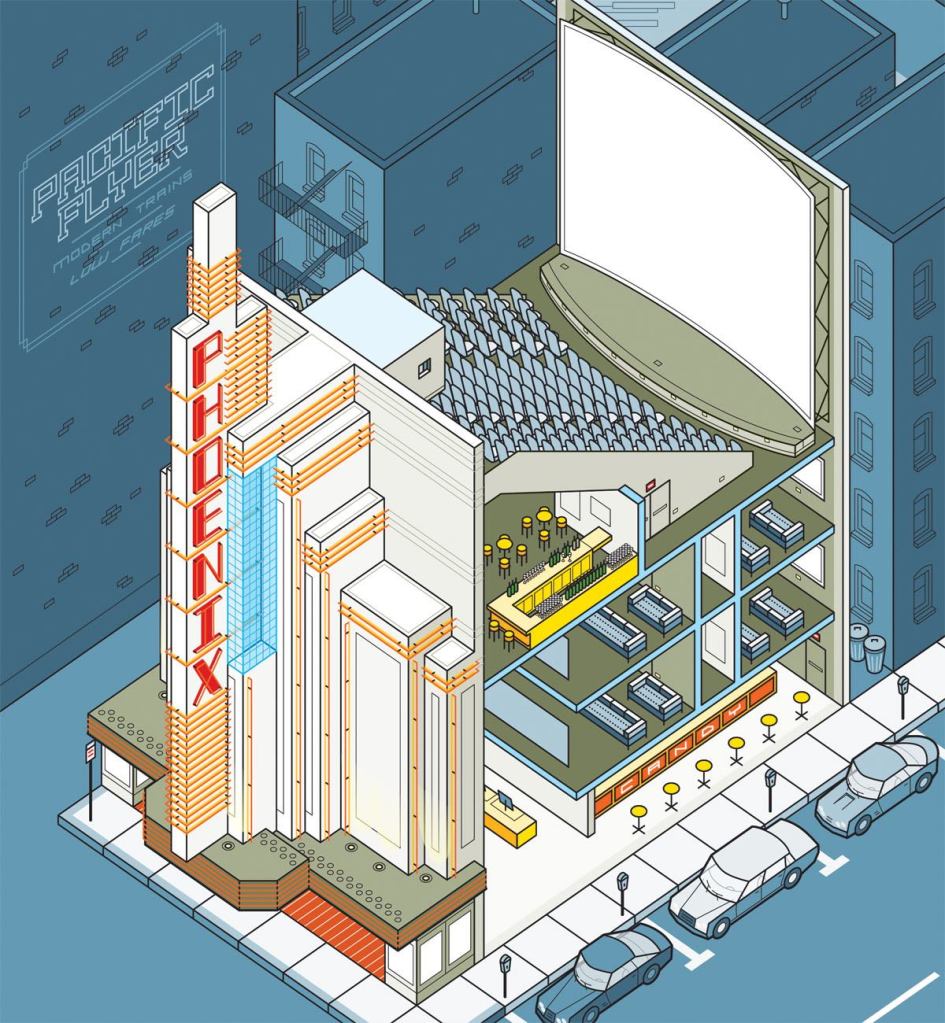

Last fall, the company ushered in its new design concept at the 100,000-square-foot, 18-screen Rosemont Theatre outside Chicago. The Rosemont, with auditoriums ranging in size from 135 seats to 380 seats, is an updated version of the classic prewar movie palace and cost about 10 percent more to build than the themed cinemas. “We wanted an architectural design that complemented the luxury experience, and we looked back to the ’20s and ’30s for inspiration,” Wilson explains. DDG gave the complex an ornate façade and flashy marquee. Rosemont offers perks such as childcare as well as a “premiere” experience: For $20 per ticket, customers can use a separate entrance with a valet and can access a private second level through a dedicated set of escalators. Once there, they can dine at a high-end, 300-seat restaurant that overlooks the bustle of the general-admissions lobby below.

Muvico is not alone in reviving the movie palace concept. Pacific Theatres, a chain based in California, recently opened a new theater in a mixed-use complex in Los Angeles called The Grove. The theater’s sweeping Art Deco lobby is bedecked with massive chandeliers. Ushers wear 1920s-inspired outfits, complete with little hats. A photo exhibit honors the great movie palaces of California and the architects who built them. Adjacent to the lobby is a restaurant called The Farm, serving contemporary Californian cuisine. Although it is not part of the theater, patrons who can’t finish their $16 goatcheese salad are invited to bring leftovers into the movie.

As the movie palace concept becomes commonplace, it is also merging with the once-rarefied art-house experience. Muvico is developing “allpremiere” theaters in urban settings that will run independent films and cater to the 21-and-over crowd. Pacific has two cinemas in California under its ArcLight Cinemas brand. These have amenities such as reserved seating, a café and bar, a retail store, concierge assistance, and a lineup of primarily art-house shows and Oscar-nominated movies. ArcLight recently retrofitted Hollywood’s Cinerama Dome, a Fuller-inspired geodesic theater originally built in 1963.

Last year also saw new companies entering the marketplace, notably Sundance. Robert Redford’s brand opened its first-ever theater in Madison, Wis. TK Architects partnered with interior architect Kahler Slater and graphic designer Graham/Little Studio to create a multistory space with a full-service restaurant and bar as well as a gift shop selling products from the Sundance catalog. The complex is capped with a rooftop bar, which is “a rousing success during the six months of the year that they can keep it open,” Cummings jokes. Sundance opened a second theater in December in San Francisco and has plans for two more this year in Denver and Chicago.

IMAX: THE NEW STADIUM SEATING?

The moviegoer’s experience inside the theater itself is changing, too. Since its inception in 1967, IMAX has lured audiences with its digital surround sound and large-screen format. Once the domain of specialty theaters and museums and institutional spaces, IMAX went more mainstream in 2002 when it released IMAX DMR, a digital remastering technology that allowed any Hollywood film to be transformed into the IMAX format. In 2007, the company launched a new digital projection system. The switch to digital essentially eliminates the need for film prints and costly film projectors. “For the exhibitor, it’s an opportunity to get IMAX into their theater at a lower price point,” says Larry O’Reilly, IMAX’s executive vice president of theater development.

IMAX is partnering with movie exhibitors, including Regal Entertainment Group, to bring its technology into more multiplexes. In October, the company announced an additional partnership with mega-chain AMC that will put IMAX in more than 100 AMC theaters around the country. Currently, IMAX has 150 theaters in the United States, of which 68 are in a multiplex setting (the rest are in institutions such as museums). By 2009, the number in multiplexes will have more than doubled.

Although it’s less expensive than it used to be, IMAX is still an investment. It requires auditoriums of at least 300 seats with high ceilings to accommodate its screens. And because those screens skim the floor (for that big-picture, full-immersion experience), steeper risers sometimes have to be built to preserve sightlines.

TK has retrofitted IMAX theaters into existing cinemas in Las Vegas; Mesa, Ariz.; and Knoxville, Tenn. TK is also working to build IMAX into four new projects, including one under way in Reading, Pa. “The city and the local developer were very interested in having IMAX as a community asset,” says Cummings. “The [extra cost was] $1 million, with half for the additional equipment and half for added construction.”

Could IMAX be the next stadium seating? “We’re not stealing existing audiences away from other theaters. We’re growing a new audience,” O’Reilly says. He cites exit surveys showing that people who pay for an IMAX show might not have come to the theater at all if not for IMAX.

Sounds familiar. We’ll see what happens in 11 years..