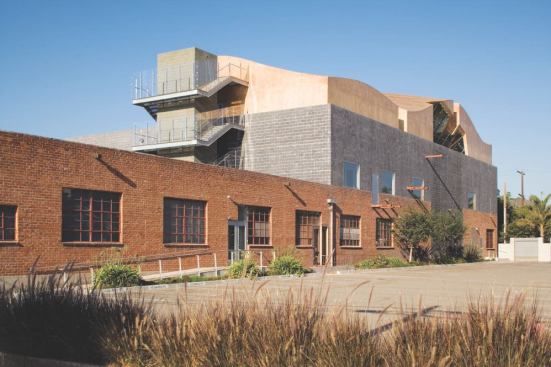

Tom Bonner

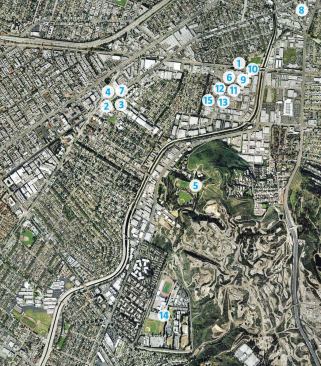

3555 Hayden, Culver City, Calif.

Sloped Glass

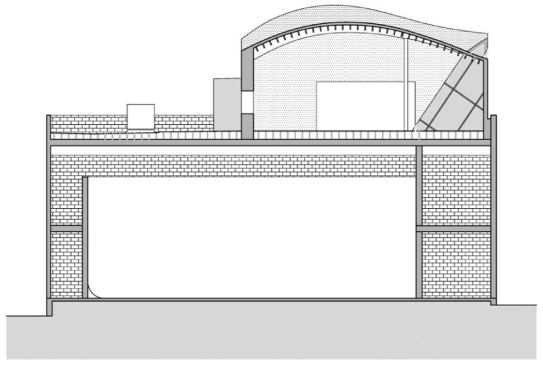

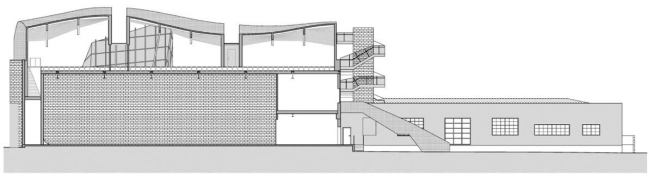

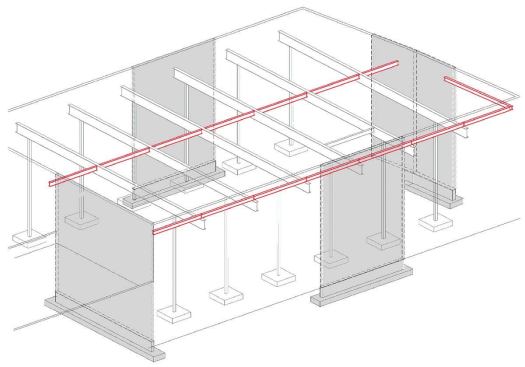

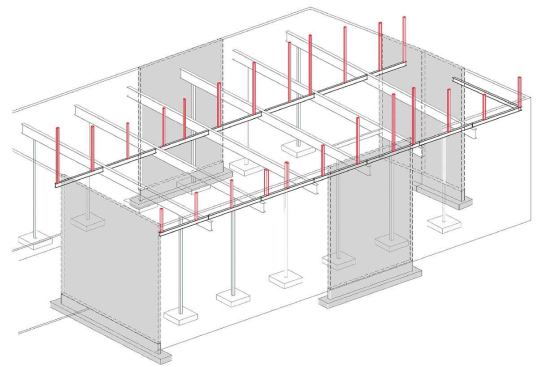

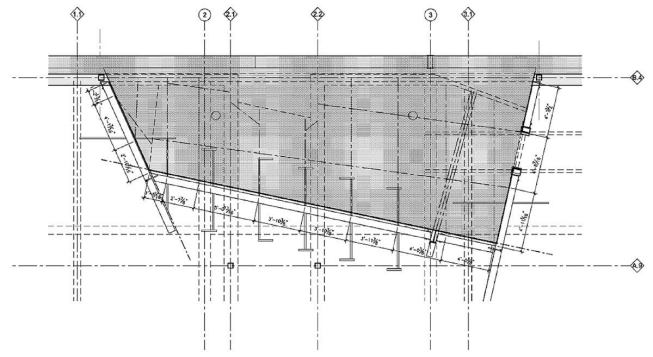

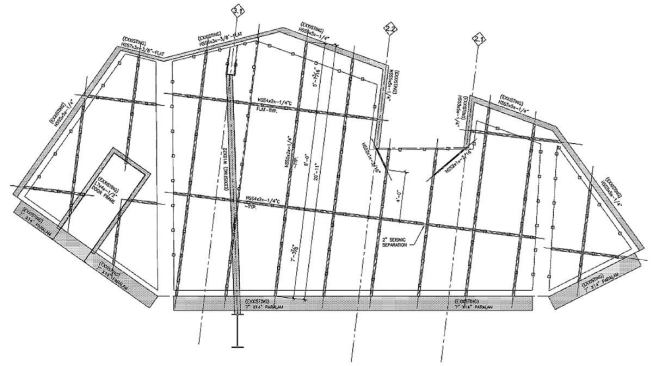

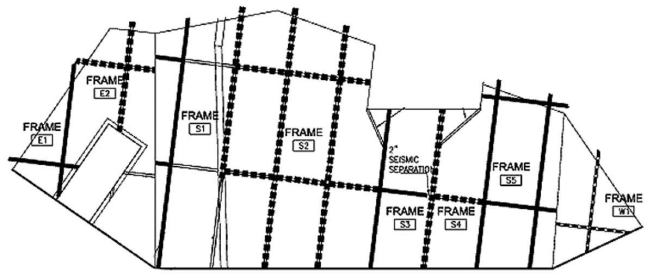

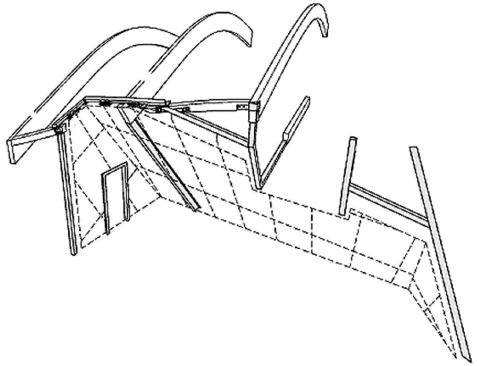

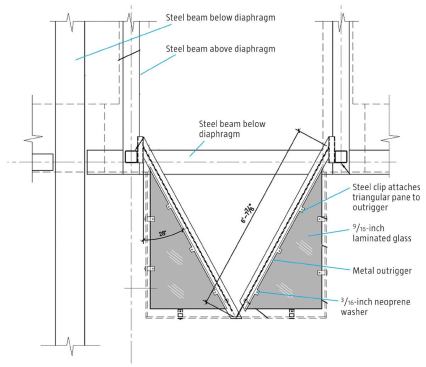

As if they hadn’t pushed the limits far enough, Moss’ team decided to penetrate the curvilinear geometry of the roof with three slanted planes of glass. The result is a sheltered balcony on the north side of the building that affords sweeping views over the rooftops of Culver City toward the cluster of high-rises in Century City. The sloped glazing was conceived as a cut into the building, conceptually slicing into and removing a portion of the wall and roof surfaces and framing. Its three planes are angled at 0, 20, and 35 degrees from vertical—rakes derived from the path of the sun and intended to bring a generous amount of indirect sunlight into the building.

The act of cutting through the building informs the glass wall’s aesthetic qualities, detailing, and relationship to other materials in the roof and walls. The conceptual cut is detailed with rafters, beams, and a skylight butting against the glass surface and appearing to hang unsupported. “There’s not an acknowledgment of two systems responding to one another. They are actually smashed into each other,” says Tom Raymont, a member of the design team. “But the act of smashing them into each other is actually very carefully detailed and becomes a kind of aesthetic concept throughout the building.”

The wall consists of an aluminum storefront system that was heavily reinforced with steel to support the acute angle of the glass. The framing module is staggered from wall to wall so that, at the corners, the steel cross-members pass each other in space instead of connecting at the intersection. In order to set the glass into a precise plane, it was necessary to provide an adjustable connection back to the steel grid. This was accomplished with an aluminum mullion cap that slotted over the steel framing and could be held off by as much as an inch.

Fiberglass Coating

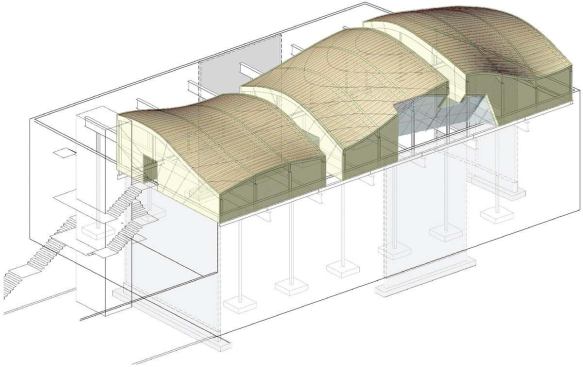

The rooftop addition is coated in a monolithic shell of fiberglass—or, to be more accurate, glass fiber–reinforced plastic. With so many variables at play, extensive research and testing were necessary to develop the appropriate balance of resin, color, texture, substrate, and strength. The best collaborators emerged from the swimming pool industry, whose crews routinely spray fiberglass to repair or recoat existing pools on site.

Moss wanted the surface quality to resemble cloisonné, a glass-based glaze with a subtle depth of surface. A number of green shades were tested, but in the end he selected a resin with no pigment—only the imbedded golden tone of the material itself. Early on, the architects thought of fiberglass like stucco, believing that a mesh backing would hold it firmly in place (see images at right, top). Their experiments revealed that the glass fibers did not key into the mesh whatsoever, so they abandoned that approach and went instead with a solid substrate coated with primer that would adhere chemically to the fiberglass layer.

Mock-ups were done with a variety of metal flashing profiles to design an expansion joint for the roof (see images at right, middle right). Those options were rejected in favor of a flexible foam backer rod that was cut into half-round sections on a band saw. In addition to controlling expansion, the resulting joint also serves to mitigate the flow of rainwater off the roof. As a design element, the joints are laid out as a series of continuous ribs across the roof like topographic lines (see images at right, bottom). One lesson learned: Because the ribs are horizontal, they acted like dams, creating shallow pools of water. When short sections were cut from the ribs to allow water to drain down, cracks developed in the fiberglass at those points. The cracks have been repaired with silicone.

Applying the fiberglass is an art form in itself. After coating the roof surface with a thin layer of resin and catalyst, the work crew began to spray on the final mixture, which has the appearance of wet grass when first applied (see images at right, middle left). The art, and risk, come with using a manual process to achieve the desired 3/16-inch coverage. Too much spray, and the color goes dark; too little, and it appears faded. Enormous care was required, therefore, to create a relatively uniform color (although a certain degree of variation was also seen as desirable).

Toolbox

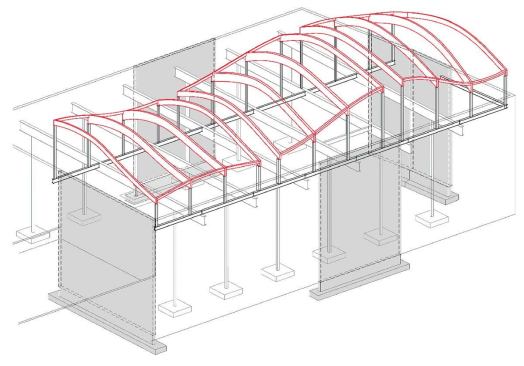

The roof geometry of compound curves and wavelike glue-laminated beams introduced a host of challenges in the design and fabrication of 3555 Hayden. To get the job done, the architects uncovered solutions both widely available and highly improvised.

Rhino / rhino3d.com Invaluable when working with complex geometries, Rhino was used to build a complete 3-D computer model of all the roof framing members: beams, rafters, and wall top plates. In the case of the beams and top plates, the 3-D data was used in fabricating the members as well.

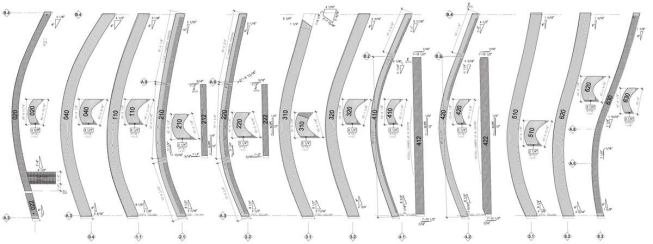

AutoCAD / www.autocad.com This reliable tool was used extensively for all 2-D work. For the rafters, which are only 1½ inches thick, two-dimensional outlines were sufficient to communicate the dimensions to the fabricator.

Structurlam Products / www.structurlam.com This Canadian company, based in Penticton, B.C., owns one of the largest CNC milling machines in the world, a Creneau machine capable of working material up to 100 feet long, 15 feet wide, and 5 feet high. Threedimensional files for the building’s curvilinear beams were e-mailed to Canada; 12 weeks later, the beams arrived in Southern California on a truck.

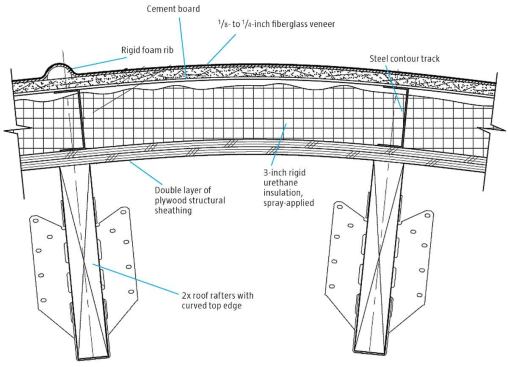

Contour Track / www.dietrichindustries.com To achieve a consistent, reliable spacing for the insulation gap between the plywood ceiling and the substrate for the plexiglass roof covering, the team investigated several options. Ultimately, a new product, Contour Track by Dietrich Metal Framing, proved to be the ideal solution to create a 35/8-inch insulation cavity while lending structural integrity to the roof.

GlasRoc by CertainTeed / www.certainteed.com Moss’ staff investigated a number of sheathing materials that would bend across the roof surface without cracking. Several types of sheet material were empirically studied in a “peel test” as well to determine their bond strength with the fiberglass coating. In many cases, the layers of fiberglass readily peeled away—but not with GlasRoc, which has glass fibers that bond with the applied resin. The ½-inch-thick material has a minimum bending radius of 6 feet.

Fiberglass

The final coating on the roof is glass fiber-reinforced polyester resin. The resin was provided by Hexion; the glass fibers and catalyst are generic. The coating—applied to a thickness of about 3/16 inch—was sprayed onto the building by a crew from Protective Coatings & Linings, a company that specializes in the repair of swimming pools and industrial tanks.

Handmade fork Using standard 2x4s, the architects constructed a 6-foot-long, two-pronged fork that could be slotted over a rafter and used to twist it into position when the ends were nailed off. This twisting was necessary to ensure that each rafter met the beams at 90 degrees at both ends.

PROJECT 3555 Hayden, Culver City, Calif.

OWNER A national broadcasting company (withheld)

COST Withheld

ARCHITECT Eric Owen Moss Architects, Culver City—Eric Owen Moss (principal); Andrew Wolff (project architect); Amy Drezner, Pegah Sadr Hashemi Nejad, Jose Herrasti, Kyoung Kim, Eric McNevin, Herbert Ng, Tom Raymont (project team)

GENERAL CONTRACTOR Samitaur Constructs, Culver City—Peter Brown (director of field operations); Tim Brown (general superintendent)

STRUCTURAL ENGINEER Englekirk Partners Consulting Structural Engineers (Vladimir Volny)

STRUCTURAL STEEL Cal State Steel (Dave Olson)

HEAVY TIMBER Structurlam Products (Kris Spikler)

CNC-MILLED RAFTERS Spectrum Oak (Mark Blaustone)

ELECTRICAL Moses and Associates (Raymond Moses)

MECHANICAL/PLUMBING The Sullivan Partnership (Mark Alcalde)

FIBERGLASS COATING Protective Coatings & Linings (Bud Cook)

SLOPED GLAZING Dandoy Glass (Doug Dandoy)