If you ever visit a Whole Woman’s Health Clinic, part of a national chain of reproductive care facilities, you might notice that it doesn’t resemble a traditional health care space. Soothing lavender paint covers the walls and lamplight replaces harsh fluorescents. Diffusers steam calming essential oil, while a specially blended herbal tea, featuring peppermint for nausea and rose for cramping, steeps for patients. Exam rooms aren’t numbered; they’re named for inspirational women such as Frida Kahlo and Rosa Parks.

Amy Hagstrom Miller, founder and CEO of Whole Woman’s Health, opened the first clinic in Austin, Texas, in 2003, and she prioritized the patient experience. Hagstrom Miller is the daughter of a custom homebuilder and the sister to a landscape architect, and she has always been attuned to the psychology of space. “I grew up thinking about design,” Hagstrom Miller says, and “about how space can contribute to stigma or how it might help to alleviate stigma.”

Hagstrom Miller now oversees eight existing reproductive health care clinics around the country, in states like Virginia and Indiana, and she has renovated each using her signature patient-centered approach. While Hagstrom Miller values design, she never could budget for an architect, at least not until 2014, when she hired Illinois-based George Johannes, AIA. His job wasn’t the design of a new clinic; rather, he was tasked with helping to save existing ones.

Among the many gynecological services offered by Whole Woman’s Health—Pap smears, ultrasounds, birth control—the clinic also provides abortion care. This makes Hagstrom Miller’s buildings among the most targeted in the United States. Just last spring, in the middle of the night, someone attempted to burn down the Whole Woman’s Health Clinic in McAllen, Texas, before a neighbor saw the smoke and called 911. Hagstrom Miller and her staff have spent decades ushering women past protesters and contending with threats, violence, and sabotage, but the clinic’s biggest challenge right now is regulatory codes.

A Whole Women's Health Clinic in Austin

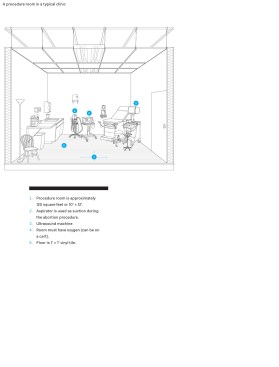

In 2013, Texas passed House Bill 2 (HB2), which placed new, more stringent regulations on abortion clinics. The World Health Organization has classified abortion as a safe procedure for outpatient clinics and physician’s offices, which is where 95% of abortions take place in the U.S, according to the National Abortion Federation (NAF), the professional association for abortion providers. But HB2 mandated, among other things, that providers must come into compliance with ambulatory surgery center (ASC) standards. ASCs are a step up from medical offices and provide outpatient surgeries that do not require hospital stays—think knee replacements—requiring facilities to include at least one dedicated operating room. HB2 meant that abortion providers across Texas had to upgrade corridor widths, door and exam room sizes, and HVAC systems, among other things. HB2, proponents argued, would help protect women with a higher standard of care. “This is an important day for those who support life and for those who support the health of Texas women,” said then-Governor Rick Perry when the legislation passed.

For Hagstrom Miller and opponents of HB2, the true intent of the law was obvious, and it wasn’t about patient well-being. The legislation has “nothing to do with the actual procedure that we’re providing,” Hagstrom Miller says. The statutes “were imposed on us because the opposition knew it would be extremely difficult to comply, and it would be incredibly onerous and expensive.”

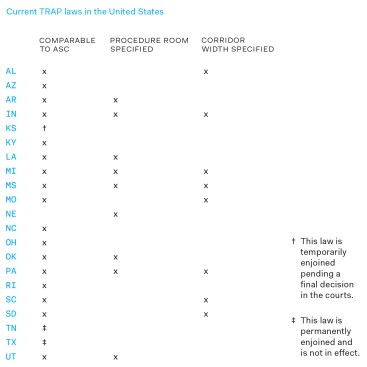

HB2 is what’s known as a Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers—or TRAP—law. TRAP refers to legislation specifically related to the physical building, equipment, and staffing requirements of a facility that performs abortions, according to Elizabeth Nash, senior state issues manager at the Guttmacher Institute, a sexual and reproductive health and rights research and policy nonprofit. The term was coined by the Center for Reproductive Health in the 1990s, Nash says, but zoning and building codes were used to limit abortion clinics as soon as the landmark Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade made abortion legal in 1973. Following the 2010 midterm elections, when many state and local legislatures went red, hundreds of new TRAP laws were passed in the U.S. Far from being motivated by a question of safety, Nash says, TRAP laws in the last decade have become the primary tool used to hinder access to legal abortion care in America.

“We work within codes as a profession, and I want to believe that regulations have been arrived at by rational, honest people of integrity, and that they are evidenced-based. When those same tools are used for political purposes, it calls into question the whole system. That should concern every architect,” Johannes says, because “when you start using codes as a political cudgel, who is next?”

When HB2 passed, Hagstrom Miller and several clinic providers brought Johannes to Texas to help quantify the impact of the ASC standard. Johannes had designed an abortion clinic in Illinois in the 1990s and consulted on the design and code compliance of several others. He teaches professional practice courses, including building codes, at the Graduate School of Architecture & Urban Design at Washington University in St. Louis. “Publicly, Texas was saying that these regulations weren’t that expensive or difficult, that they weren’t asking for much,” Johannes says. “My job was to determine what exactly this law meant to the clinics. And of course the cost was either huge or implausible. Implausible because many clinics were in small buildings on sites where they couldn’t even put on an addition.”

Johannes visited eight Texas clinics in 2014 and determined that meeting the new code would cost providers in the millions. At Whole Woman’s Health in Austin, the cost estimate was up to $2.4 million. Hagstrom Miller took those estimates and visited 15 banks. Some denied her outright because, she believes, they didn’t want to work with an abortion clinic. Others simply couldn’t make the math work. The cost of the services provided at Whole Woman’s Health are capped in order to allow individuals from all socioeconomic backgrounds to afford care. Hagstrom Miller was told that her business model was never going to be able to pay for the expense of upgrading her buildings.

Then there was the added cost of facility management. When Hagstrom Miller did manage to turn one of her Texas clinics into an ASC, the cost to run it was 40% higher, in part owing to the refrigeration and HVAC standards, but also because of the staffing regulations. ASCs require more nurses per patient because there is a presumption of an invasive surgical procedure.

Hagstrom Miller also noticed the effect her ASC-compliant facility had on patients. The soft lavender color scheme was replaced with an industrial white paint meant to ease in the clean-up of blood splatter, which she says is an unnecessary restriction in the case of abortion. Nurses were required to “garb up” and wear full protective gear and face masks, creating a sterile and impersonal environment. “Complying with those physical plant requirements changes the way not only we practice the care, but the way people experience the care,” Hagstrom Miller says.

Whole Woman’s Health brought a lawsuit against the state of Texas challenging HB2, and Johannes testified as an expert witness. The case reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 2016, and in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, the court ruled by a 5-3 vote that the ASC statute was unconstitutional. In the affirming opinion, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg wrote that “many medical procedures, including childbirth, are far more dangerous to patients, yet are not subject to ambulatory surgical-center or hospital admitting-privileges requirements,” adding that “it is beyond rational belief that H.B. 2 could genuinely protect the health of women, and certain that the law would simply make it more difficult for them to obtain abortions.”

Amy Hagstrom Miller after the Supreme Court ruled in her favor in 2016

By the time of the Supreme Court decision, however, many Texas clinics had already been forced to close. The state had more than 40 abortion clinics before HB2 was enacted. After portions of the law went into effect, it had 17. If not for a legal injunction delaying the implementation of the ASC-standard, fewer than 10 clinics would have remained open. Hagstrom Miller’s Austin clinic was among those that closed.

The debate over TRAP laws, meanwhile, is far from over. In March, the Supreme Court, which has tilted to the right since the Texas case, heard oral arguments in June Medical Services v. Russo, a case over a similar law in the state of Louisiana. Today, more than ever, the battle over a woman’s right to choose is being waged in the built environment.

A Politicized Design Challenge

Abortion clinics offer a compelling, if complex, design challenge: How do you take a politically contested space and make it secure and safe, while also creating a positive environment for the community, staff, and patients? The challenge has only intensified in recent years. Since 1977, NAF has tracked vandalism, trespassing, arson, and some 100 incidents of butyric acid attacks on clinics. In its 2018 report, the foundation outlined a dramatic increase in violence and disruption, including “an escalation in vandalism, trespassing, hate mail/harassing phone calls, internet harassment, picketing, and obstruction.” Violence against clinics, NAF reported, has reached a record high.

Because of politics, protests, and attacks on clinic buildings, abortion providers contend with what’s been dubbed “the abortion tax.” It can be difficult for a provider to find an owner willing to lease to a business offering abortions. This isn’t always political; building owners simply may not welcome the protesters and the damage to property that can result from attacks. Recently, Hagstrom Miller spent months trying to find a facility in Minneapolis willing to lease to Whole Woman’s Health, but ultimately the organization had to fundraise to purchase a building.

Starting from scratch presents its own challenges. When Johannes designed the Hope Clinic for Women in Granite City, Ill., the exterior wall edged the property line of an organization that, because of its stance on abortion, refused to allow scaffolding on its land. This meant a costly last-minute change order with the builder who had to figure out how to construct the wall from the inside out by lifting masonry over the interior building slabs. Even getting that masonry proved difficult; one major purveyor of the decorative concrete blocks used in the building refused to sell to an abortion clinic, leading to what Johannes says was a lack of competitive bidding that added unnecessary costs to the bottom line.

Stephen Yablon Architecture

The main waiting room in the Queens Planned Parenthood

Michael Moran

The recovery area in the Queens Planned Parenthood

For the first Planned Parenthood in Queens, N.Y., completed in 2016, Stephen Yablon Architecture (SYA) had to rely on a smart distribution of limited resources. The renovated 14,400-square-foot warehouse on a mixed-use street earned an AIA/AAH Healthcare Design Award for its use of light, interior wayfinding, color palette, and an exterior brick façade with large windows connecting to the neighborhood. Andrew Miller, AIA, an associate partner and director at SYA, says the project was about “doing a lot with a little,” owing to a tight budget, a portion of which had to go towards ballistics glass on the exterior. Bulletproof glass is “not a typical material except in very high security situations,” he says, “and it’s an expensive product, so it does have a significant cost impact.”

Once operational, providers must also plan for myriad security threats against staff, clients, and the building. In addition to the list of crimes tracked by NAF, there’s a long history of sabotage to the buildings that house clinics, including the destruction of exterior HVAC units. Johannes cleverly planned for this possibility when he designed the Hope Clinic—using a strategy he didn’t want to reveal on the record. He also mentioned various methods used to target abortion clinics over the years, resulting in costly repairs, loss of lease, or closures, but also declined to disclose them for fear of providing a playbook to extremists. Johannes learned about many of these tactics because his wife, Sally Burgess, was executive director of the Hope Clinic (they met while he was working on the project); she also served on the board of NAF for many years. Johannes has attended national meetings of the foundation to offer presentations on security design. Clinic operators are “highly sensitive about the risks,” Johannes says, and even if they could afford design consultation with an architect, few could afford to implement the plan. “A lot of clinics are vulnerable for that reason,” he says.

Stephen Yablon Architecture

The project's color palette and use of light and wayfinding help it earn an AIA/AAH Healthcare Design Award

Another challenge with building or renovating is that subcontractors may refuse to work on a clinic offering abortion care either because of their personal beliefs, or because they worry about the optics. Architects and providers that I interviewed told me that the subcontractors who did say yes sometimes received hate mail or dealt with protesters swarming other jobsites in an effort to publicly shame them.

In response, some providers have started to renovate or build discreetly. In 2019, when a new Planned Parenthood opened in Illinois, the Fairview Heights Center, it was developed with its purpose kept hidden. The center was built to bring reproductive care, such as annual exams, Pap smears, and cancer testing, to the local community, but it also serves as a regional hub: across the river in Missouri, because of TRAP laws and other regulations, only one abortion clinic remains. Kristin Flood, senior director of health care regulatory strategy for Planned Parenthood Federation of America, says that “due to the targeted regulations on abortion providers and anti-abortion activists, we sometimes have to use additional measures while planning and building Planned Parenthood health centers to ensure that our facilities are built on a timely schedule so that we can provide quality care as quickly as possible in the surrounding area.” Planned Parenthood’s national office wouldn’t go on the record about specific development strategies, but other providers told me that one of the primary tactics is to create a shell developer for the public record.

Legal Whack-a-Mole

The TRAP laws have only made the design challenge more difficult. Today, according to data collected by the Guttmacher Institute, 24 states carry laws or policies that require abortion clinics to follow measures that providers consider unnecessary for the health and safety of patients. Currently, 17 states have laws mandating that clinics comply with structural standards comparable to surgery centers. In addition to the ASC statute implemented in Texas and other states, some new legislation has imposed zoning regulations stating that clinics cannot be located near schools or that they must stock expensive surgical equipment and prescriptions. The laws have also stipulated that clinics must exist within a certain proximity to hospitals—a challenge especially in rural locations—and that clinic doctors must gain admitting privileges, something that many hospitals refuse to grant.

Source: Guttmacher Institute

The spate of new legislation has been inspired in part by Americans United for Life (AUL), a self-described public interest law firm that has created model legislation adopted by many states. Each year they publish “Defending Life,” what they call a “pro-life playbook,” and this year’s edition includes more than 50 pieces of model law and policy. In a 2018 booklet titled “Unsafe,” AUL wrote that “To ensure that laws designed to protect women and their children from abortion industry abuses remain on the books and are properly enforced, pro-life Americans and their representatives must actively and effectively counter the enduring abortion-industry-manufactured myths that ‘abortion is safe’ and that ‘abortion is between a woman and her doctor.’ ”

Opponents of TRAP laws note that abortion providers already follow federal OSHA regulations and state health and safety licensing requirements for medical facilities, and they cite the overwhelming evidence that abortion is in fact safe. In 2018, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine conducted an in-depth study that found abortion, as practiced, is safe, and noted that the procedure can be performed by nurse practitioners. In fact it is the “abortion-specific regulations in many states [that] create barriers to safe and effective care,” the report said, including some laws that apply ASC regulations to clinics that only offer medical abortions, in which a woman takes a pill. The same year, researchers at the University of California, San Francisco and Penn State College of Medicine conducted a study, published in the peer-reviewed medical journal JAMA, that found little evidence to support the assertion that abortions are safer in an ASC rather than an office-based setting. According to data gathered by the Guttmacher Institute, fewer than 0.5% of abortions result in a major complication requiring hospitalization. Physician David A. Grimes, who served as Chief of the Abortion Surveillance Branch at the CDC, has written that “the risk of death from abortion in the U.S. is similar to that of paddling a canoe.”

“The reality is, abortion is already being banned without ever overturning Roe,” says Flood, who works with Planned Parenthood affiliates around the country to understand how state laws and regulations affect facility design. “There is a multilayered effort, which includes building restrictions, general abortion restrictions, and municipal codes that push abortion out of reach.”

courtesy Seth Denizen/SCAPEGOAT: Architecture | Landscape | Political Economy

courtesy Seth Denizen/SCAPEGOAT: Architecture | Landscape | Political Economy

In a 2016 article for the peer-reviewed journal Critical Public Health, lead author Rebecca J. Mercier of the department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University and fellow researchers found that abortion provisions in the U.S. have become “a dance” between lawmakers and providers. “The challenge for anti-choice lawmakers is to write abortion restrictions in a way that complicates access, but not to such an extent that they impose a blatant undue burden on patients, which will not stand up in court,” the researchers wrote. “The challenge for abortion providers is to meet the standards of the law, which may require extensive changes to a clinic’s physical structures and patient care procedures, so that they can continue to operate legally and ensure abortion access. In this way, the abortion provider, and the steps she takes to adapt to the ever-changing regulatory landscape, becomes an essential component of protecting abortion access throughout the country.”

In Memphis, Katy Leopard, director of external affairs for Choices: The Memphis Center for Reproductive Health, refers to TRAP laws as legal Whack-a-Mole. “You never know what’s going to pop up next,” Leopard says. Choices is an independent clinic that has been offering abortions in Memphis since 1974, and later this spring, their new facility will become the first in the U.S. to offer both a birthing center and abortion care in one place. Memphis-based architect Peter Warren, AIA, of Warren Architecture, was hired to design the building. “I knew it wasn’t the simplest project to say yes to,” says Warren, “but my core belief is to support a woman’s right to choose. I’ve never been an activist for the cause, but when the call came for this project, it was an opportunity to do something that I felt was right.”

Warren had to weigh two primary concerns: the shifting regulations on clinics and the privacy and safety of staff and patients at a place where protesters regularly gather. Sitting just 10 feet off a public sidewalk on busy Poplar Avenue near downtown Memphis, the new clinic is clad in a colorful metal panel system Warren designed to resemble a quilt. He wanted the building to appear strong, vibrant, and visible. “They are advocates for education and protectors of women’s rights,” Warren says of Choices. “They don’t want to do that from the shadows.”

Choices aims to eliminate the stigma around abortion care, and part of that is by creating a safe but nurturing physical environment. “We resisted overly securing the facility because we feel like that almost feeds into the fear,” Leopard says. “We’ve taken practical steps but not gone overboard. Nobody wants to go through a metal detector to get their annual Pap smear.”

When it comes to women’s reproductive health clinics and abortion care, “the silence coming from the profession is overwhelming,” Brown says. “Where are the architects wanting to engage in these issues?”

Some of those practical steps include having the exterior façade face busy Poplar Avenue, but providing parking off a side street so the main entrance to the clinic is removed from protesters. A porch welcomes patients, and in nice weather, large doors can open to the fresh air. On the interior, ancillary rooms line the façade wall backing onto Poplar, creating a sound buffer for the interior exam rooms when protesters are shouting. The birthing center rooms on the second floor open onto an interior courtyard garden where women can move freely during labor.

Warren had to adopt a “what if” mindset when designing the building. Memphis has passed an ASC standard law, which is currently stayed following the Whole Woman’s Health decision. But in January, Tennessee Governor Bill Lee, surrounded by a phalanx of other Republican legislators, most of them male, held a press conference announcing that new abortion restrictions would be a legislative priority for 2020. At press time, that legislation—what Nash of the Guttmacher Institute calls a “mega abortion bill” for its wide-ranging regulations—was currently before the Tennessee legislature. Warren needed to make sure the Choices space met the requirements of potential new laws. He designed the entire building to the ambulatory standard, considering not only the International Building Code, but also the regulations under the NFPA Life Safety Code, which is triggered in Tennessee when a building must follow ASC standards.

Staying nimble also meant expanding the business plan, says Leopard. Choices offers services like fertility treatment for the LGBTQ community, and the first midwife-led birthing center in Memphis, in part to meet the needs of their community, but also as a reaction to TRAP laws. “Part of the strategy of diversifying is to have a business model that doesn’t depend so heavily on one service,” Leopard says. “Bringing on a major new service like prenatal care and birth we hope gives us a business model that makes us more flexible.”

That flexibility is key, because TRAP laws often do not allow for grandfathering, a common practice when new codes affect existing buildings. As soon as TRAP laws pass, clinics are often served notices of noncompliance—a practice Johannes says he has witnessed firsthand when helping abortion providers meet or fight new regulations. No matter your politics on a woman’s right to choose, Johannes believes TRAP laws should alarm the profession. “One thing that architects should be very attentive to is this: What is the purpose of a code? Of a regulation?” he asks. “We work within codes as a profession, and I want to believe that regulations have been arrived at by rational, honest people of integrity, and that they are evidenced-based. When those same tools are used for political purposes, it calls into question the whole system. That should concern every architect,” Johannes says, because “when you start using codes as a political cudgel, who is next?”

A clinic in Huntsville, Ala.

An Absence of Architects

For the most part, architects have steered clear of this controversial building type. When Warren went looking for best practices, he found little in the architecture literature. SYA’s Andrew Miller told me the same thing: “We did some research before we started working with Planned Parenthood of New York City, and found there was very little out there on similar facilities.”

Except, that is, for the research of Lori A. Brown, AIA, who teaches at the Syracuse University School of Architecture. Brown has spent years researching architecture’s role in reframing politically charged spaces. She traveled the country interviewing abortion providers as well as tracking data related to their design needs. Most clinics do not use an architect, Brown says, because “they simply can’t afford it, or they aren’t clear on what architects can do to help them.” TRAP laws also make fundraising difficult, because “people don’t want to give money to a building that might have to close in six months.”

In her 2013 book Contested Spaces: Abortion Clinics, Women’s Shelters and Hospitals, published by Ashgate (now Routledge), Brown cataloged the detrimental effect of spatial politics on women, particularly women of color and those living in poverty. In a 2016 article for ARPA Journal, she wrote that, “Abortion clinics raise complex questions about the fluid and ever-shifting terrain of reproductive healthcare access,” and about “how architectural thinking can bring forward new insights into the built environment of everyday space.”

In 2014, Brown issued a call for design ideas for a project called Private Choices Public Spaces. The challenge, open to the public, asked participants to consider the design of a security fence around the Jackson Women’s Health Organization in Jackson, Miss. Of the many ideas submitted, one called “Roses and Thorns: the anti-fence that flourishes” suggested a horticultural response, while another envisioned a clever use of fountains to block the clinic from protesters. As Brown wrote in her ARPA article, she considered the exercise “a platform to raise awareness about the role design could contribute to public space—especially in such an underexamined and contested space.”

A patient at a Whole Woman's Health Clinic in Austin

Using the built environment to manipulate women’s bodies is nothing new, says Malkit Shoshan, a lecturer in architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. In fall 2019, Shoshan curated a show at the GSD titled Love in a Mist: The Politics of Fertility. It examined the myriad ways society has exerted control over women and fertility, and included art and design by the likes of Dutch physician Rebecca Gomperts, who in 1999 built Women on Waves, a clinic-on-a-ship meant to anchor in international waters and bring reproductive health care to women in countries with restrictive abortion laws. Born in Israel, Shoshan realized at an early age “how architecture and urban planning can be used to promote politically or ideological agendas,” she says. “Architecture can be complicit in the creation of unsafe environments.”

Architects don’t typically shy away from dialogue about contested spaces, or their impact on health and wellness. What role architects should play in the design of prisons for example—or the proposed U.S.–Mexico border wall—has inspired robust debate within the profession. In 2014, when migrant workers began dying while building World Cup arenas in Qatar, the backlash was swift. As it was when Bjarke Ingels posted a photo of himself with Brazil’s far-right president Jair Bolsonaro in January. And when the Trump administration voiced its desire to limit the architectural style of federal buildings in February, AIA promptly decried the shortsighted nature of political agendas dictating public design. When it comes to women’s reproductive health clinics and abortion care, however, “the silence coming from the profession is overwhelming,” Brown says. “Where are the architects wanting to engage in these issues?”

Some of that silence is understandable. A few architects I interviewed for this story told me they worried about boycotts from clients who don’t approve of abortion; one declined to go on the record because they worked in a conservative state where their longtime role in designing clinics would be controversial.

She’s trying, always, to wrap her head around the abortion clinic conundrum, what those in the design world dub a “wicked social problem.” She has one question that she always poses to the designers. “How can the design of a building contribute to, or alleviate, stigma in a place like an abortion clinic?”

Anne Fougeron, FAIA, principal of San Francisco–based Fougeron Architecture, is one of the rare architects who has spoken widely about her work on clinics. After a gunman murdered two people and injured five more at Planned Parenthood in Boston in 1994, Fougeron helped to design the organization’s Bay Area offices, call centers, and new clinics at pro bono or reduced rates. “Being an architect and a woman and having a daughter, it was important to me to help protect the rights that we had won with Roe,” Fougeron says. “Those rights are being eroded on a daily basis, and one way was through violence. I was interested in ways of addressing that issue and providing people with better places to receive health care. And I still feel that way because it’s only gotten worse.”

For Fougeron, as for Brown, there’s a moral impetus for designing women’s reproductive health clinics beyond just protecting abortion rights. Many women rely on these clinics for routine and preventive care, and the TRAP laws have limited their access to it. Fougeron, who earned a Distinguished Practice Award from AIA California in 2019, appreciates that architecture is a service industry. She is not aware of losing any projects, or of potential clients blackballing her, because of her work with Planned Parenthood, but says that she went in knowing that was a possibility. “Sometimes, you do things because you have a social conscience, because you have to do them,” she says.

Johannes vividly remembers the day in 2009 when colleague and friend George Tiller, an abortion doctor in Wichita, Kan., was gunned down while serving as an usher at his church. Johannes consulted with the new director on the code compliance necessary to re-open Tiller’s clinic after his death. “There’s probably a few of us in the country that are actually deeply involved in this, but not very many,” Johannes says. “This isn’t being discussed at a broader level, which is unfortunate because that silence gives a certain amount of energy to those who really want to shut this down entirely.”

Abortion is so politicized, Brown says, “and there’s still so much shame around the procedure, and the profession is reflecting that as well, and that’s not OK. We need numbers to come out and support that [abortion] is a basic medical procedure and there needs to be well-designed spaces. But architects don’t want to touch this. I do not believe the profession is doing enough for women’s issues.”

Brown speculates whether the gender divide in architecture—a profession still overwhelmingly male—might contribute to this reality. “This is clearly a gendered medical issue,” she says. “Until there’s more gender parity in the profession, issues like this may not be a priority.”

A Whole Woman's Health Clinic

“A Wicked Social Problem”

In 2017, 10 months after the Supreme Court ruled in her favor, Hagstrom Miller was able to re-open Whole Woman’s Health Austin. She’d managed to hold on to the lease during the long legal battle by turning the clinic into a temporary co-working space, contributing her own money, and fundraising. Then in 2019, an anti-abortion organization targeting the clinic offered the building’s landlord a five-year upfront payment for the space. Hagstrom Miller was forced to move. She has a saying that she often repeats: You can be angry, but you can’t be surprised. She’s already on to the next fight, working to overturn other TRAP laws threatening her clinics’ survival. Meanwhile, she and other abortion providers are anxiously awaiting the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Louisiana case, which challenges a TRAP law that prevents doctors from providing abortion services unless they have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles of their clinic.

Over the years, Hagstrom Miller has attended several design thinking seminars. She’s trying, always, to wrap her head around the abortion clinic conundrum, what those in the design world dub a “wicked social problem.” She has one question that she always poses to the designers at these gatherings. “How can the design of a building contribute to, or alleviate, stigma in a place like an abortion clinic?”

The question inevitably stumps the room. “Nobody thinks they’re ever going to get an abortion in their lifetime until they do,” Hagstrom Miller says. “Nobody gets pregnant to have an abortion. Nobody wants to be our customer. And people come in with these ideas and these stigmas that they’ve been taught.”

“I’m always curious,” she adds, “to see who might be interested in working on this problem with us.”