Peter McBride

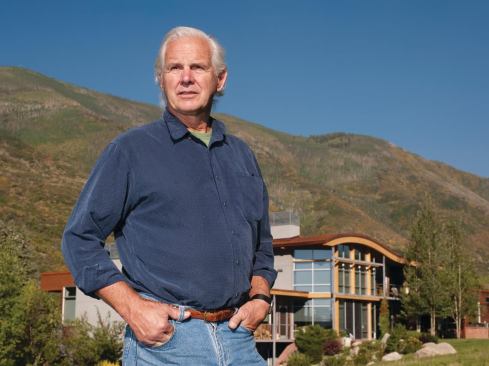

Harry Teague.

papa bear

Harry Teague speaks fondly of his early mentors: Fritz Benedict, who gave him his first job in Colorado, and Charles Moore, Moshe Safdie, and the other leading lights he studied under at Yale in the 1960s. And while he struck out on his own early in his career, Teague has long embraced mentorship from the other side of the drafting board as well.

Glenn Rappaport, principal at Black Shack Architects in Basalt, Colo., credits his erstwhile boss with clarifying “the relationship between regionalism and modernism. Harry was great about all that. He’d say, ‘Go up to Leadville and drive around the alleys.’ I saw through Harry how I was going to give language to some of the things I was very attached to in the region.”

Brad Zeigel, a partner at A4 Architects in Carbondale, Colo., is still sparked by Teague’s originality some 10 years after he and fellow alumni Michael Hassig and Olivia Emery left to found their own firm. “Harry’s inquisitive, unsatisfied with the last solution,” Zeigel says. “He’s a leader in the area, and people always wonder what he’s up to. People are always knocking on his door, and it’s always open. He’s a huge influence here, but it’s more than just architecture. It’s also the Aspen Community School and what that created. He’s affected a lot of people’s lives.”

Some former associates, no doubt, would have liked to make a career in the firm, but Teague deliberately has avoided taking a partner. As sole principal, he explains, “I’m intimately involved in all design decisions in the office. It’s why I do it; the point is to be able to do this part of the work, the design work.” Architecture is a collaborative art, he believes, but the purpose of his practice is not to build a dynasty. “It’s more to engage in these quests and discoveries. And if you get the message, there’s no other choice than to go off on your own.”

back to the ranch

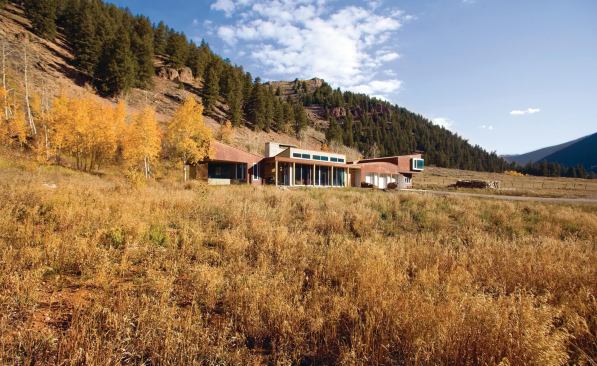

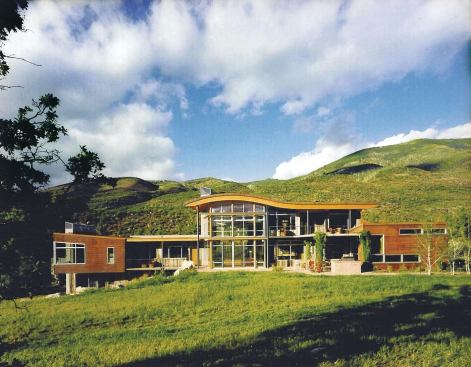

In his houses, Teague applied what had become his customary tools: intensive client research, plans that foster interaction, and forms inspired by utilitarian structures. “The agricultural buildings that I admired were often sited in a very casual way that made you say, ‘Wow, that’s just perfect,’” he observes. Taking ranch and mining camp buildings as his raw material, “I would make them up out of a lot of parts,” sculpting dwellings into the landscape, both functionally and thematically. As a result, he notes, “They looked informal, and they looked natural.”

Teague put vernacular forms at the service of an aesthetic that, while playful, was more modernist than postmodernist. And his experience as a builder gave him the confidence to employ familiar materials in novel ways. “I could just look at them and see what they could do,” he explains. About the same time that Frank Gehry made chain link fence famous, Teague used corrugated aluminum as the siding and roofing of his Shiny Metal House, contrasting the industrial material with the building’s neo-Palladian symmetry. “It’s the first example I know of people using that as a glamorous material,” Teague says.

He followed up, perhaps inevitably, with Rusty Metal House, whose untreated steel roof and siding oxidized to the same plum brown as the iron-rich rock of the nearby peaks. To sell the idea, he took his clients for a champagne picnic at the remote abandoned sheep ranch that inspired it. They agreed, Teague reports, but with conditions. “I actually had to put up a $5,000 deposit and guarantee the roof for five years.”

“Some very fine architects tend to be gardeners,” observes architectural journalist Mildred Schmertz, FAIA, who first wrote about Teague’s work in the early 1980s. “He’s influenced by the wild places. That’s a very key element in his life. He’s a mountain man.” A mountain man whose flatlander origins may actually strengthen his work. “I look at everything with fresh eyes,” Teague explains. On the East Coast of his youth, “the landscape was relatively soft. In Colorado I was plunged into this place where no building is divorced from its backdrop. Mountains shoot up behind everything. Each project deals in one way or another with an issue that the huge landscape is presenting.” Teague sought to make his buildings part of the heroic mountain landscape without making them disappear into it. Shiny Metal House “was in the bottom of a valley,” he notes, “and it had to stand out to hold its own. Our building is 5 miles long, because it forms the end of this beautiful bowl-shaped valley that’s 5 miles long. You take advantage of the features to make the building stronger.”

lay of the land

But the human element figures equally in the equation. “He embraces his clients,” says Brad Zeigel, AIA, who worked with Teague from 1990 to 2000. “He gets them to ask themselves what living is all about.” With Teague, he adds, “You get more than a house.” Teague explains: “I get very interested in the social machinery of the entity I’m working for. What do they need to make this work? Is it privacy? Is it interaction? What do they want to discover on this land? Even if it’s been done thousands of times, we go back to the source with our clients. That’s key to our process.” And for newcomers to the mountains, Teague has wisdom to share. “Right now,” he tells them, “you’re just coming to this land. All you want to do is stare at it. In 20 years you’re going to have a whole different attitude about it.”

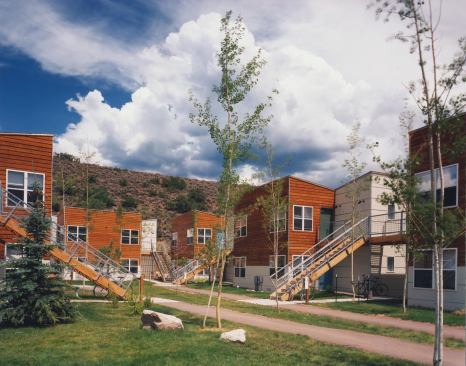

Teague’s commercial and public work—which includes an acclaimed performance hall at the Breckenridge Riverwalk Center in Breckenridge, Colo., and an ongoing series of projects at the Anderson Ranch—is equally strong, varied, and inventive. But houses remain a mainstay of his practice, and an important incubator of ideas. “Residential projects are the chamber music of our work,” Teague says. “You have the ability to experiment with this relationship with the landscape.”

This is where Teague takes his own family tradition into new territory. While neither his grandfather nor his father was an architect, he says, “Both of them did buildings—and pretty nifty ones, too.” But, he notes, “They were involved with the machine-age stuff. They were buildings that promoted an anthropocentric view.” For more than 40 years, Teague has applied his formidable skill and energy in service of a very different ideal: aligning the potential of human invention with the power of the landscape. “That’s still my theme,” he says. “You can’t beat these mountains.”