Vinyl is the most versatile and widely deployed plastic in the construction industry. In the 1950s and ’60s, manufacturers began mass-producing building components of vinyl, or polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and expanding the use of a material developed since the 1920s as a fake rubber. Today, they turn out millions of pounds of vinyl pipe in every size and shape, as well as vinyl siding, windows, decks, fences, rails, and wire coatings.

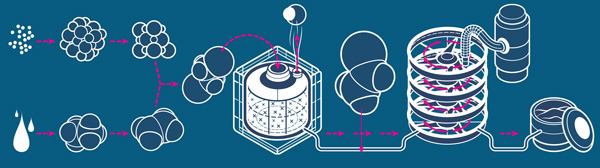

About 3 percent of vinyl is turned into roofing. To see vinyl come into beingfor the building industry, ARCHITECT watched the production of vinyl roof membranes at the plant of Sika Sarnafil in Canton, Mass. The manufacturing process at the plant starts with a powdery vinyl resin shipped by train from Louisiana, and it ends, many large rollers later, with neat 400-pound packages of a soft but tough roof sheathing wrapped around a 10-foot-long cardboard tube.

Because of vinyl’s chemical parentage—it is about 57 percent chlorine, taken from salt, and 43 percent ethylene, derived from natural gas or petroleum—its use in construction (as well as in toys and consumer products) is hotly debated. The environmental group Greenpeace calls PVC the “most environmentally damaging of all plastics.” The Healthy Building Network cites the numerous toxic substances attending PVC’s manufacture (chlorine, inparticular) as reason to remove the material from buildings, and from production, entirely.

The Vinyl Institute, among others in the plastics industry, casts PVC’s chlorine content as a plus because it means that less than half the material comes from fossil fuels. The trade group argues that PVC takes less energy to make than common alternative plastics and aluminum in construction, that it lasts a long time, and that it is increasingly recyclable. PVC pipes, notably, offer lower resistance to water flow than other kinds of pipe, requiring less energy for pumping. And Sika’s vinyl roof membranes are white on their outer face, which enables them to reflect solar heat and keep buildings cooler than dark-colored roofs. A federal government study found that installing a “cool” roof of white vinyl can reduce air-conditioning demand at peak periods by 14 percent and throughout the day by 11 percent.

Yet, among sustainable-design specialists, vinyl is under intense scrutiny. Earlier in this decade, the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) convened a special panel of experts to address a push toward creating a credit in its LEED certification scale that would reward avoiding the use of PVC products in construction. After several years of study and gathering of public comments, the panel declined to support such a credit. Rather, its final report suggested that all materials, including PVC, needed both more thorough analyses of their sustainability in the context of practical alternatives and a harder focus on the end of their lifecycles, when they may wind up, for instance, in landfills or incinerators.

As for PVC itself, the panel concluded that formally discouraging the specification of some common PVC products, such as siding, windows, or pipes, could steer designers toward products whose impacts are, on the whole, more harmful to the health of people or the environment.

Although the PVC study panel left the material’s status unchanged within the rating system, vinyl’s case is hardly closed within the USGBC. The council’s healthcare committee recently proposed that LEED discourage the use of materials involving substances known as persistent organic pollutants, which would rule out materials requiring the use of halogenated compounds—and, hence, rule out the use of PVC. “You couldn’t make PVC without halogenated compounds,” says Scot Horst, the chair of both the PVC study panel and the USGBC’s LEED steering committee. “The real problem is almost always related to the chlorine molecule,” which has the potential to create dioxins when it burns at low temperatures. Disposal, he says, isthe crucial issue. As of this writing, official action on the healthcare committee’s proposal was still pending.

“All materials have some sort of impact,” says Horst. “By reducing impact in one way, you increase impact in some other way. There are trade-offs for every decision you make.” Vinyl is a complicated material, the ultimate synthetic, and the current debate surrounding its use illustrates nothing so much as the enormous delicacy of evaluating any material’s costs and benefits when the accounting is thorough.