THREE STEPS, THREE TOOLS 1. The Sun Angle Calculator For a snapshot of daylighting effects in a building, all one needs is a plan or section drawing and a sun path diagram—commonly referred to as a sun angle calculator. This determines the effects of direct sunlight at specific times of day and year, and at specific points on the globe. The calculator registers the azimuth and altitude angles of the sun’s position in the “skydome,” an imaginary hemisphere above a flat ground plane.

Particularly useful is the sun angle calculator’s ability to identify the profile angle, the angle of the sun relative to the ground plane of the building site. When applied to a building section, the profile angle determines sunlight penetration into interiors and the effectiveness of exterior shading devices in different seasons. A helpful tool for these 2-D diagraming studies is the Pilkington Sun Angle Calculator Manual, which is available for free download from the Society of Building Science Educators website: sbse.org/resources/sac/PSAC_Manual.pdf.

2. The Model and the Sundial For an even more precise reading of the sun’s movement over the course of a day or a year, designers can turn to the good old fashioned sundial. When used with a physical model in daylight or under electric light, a sundial can help evaluate the nuances of daylight penetration for more complex forms and surfaces, such as a sloped roof or a curved wall.

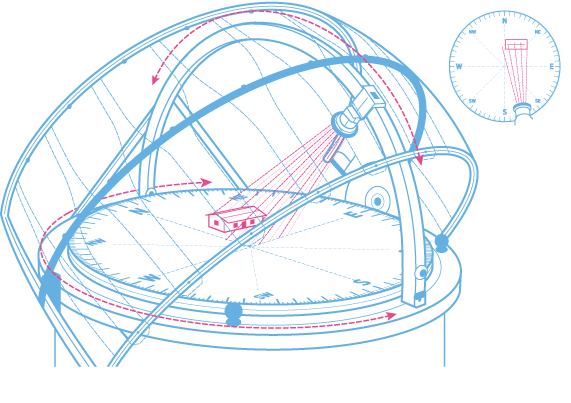

3. The Heliodon Of all the physical modeling tools for daylighting, a heliodon offers the most accurate and dynamic evaluation. There are two types of heliodons: one where the sun (light source) moves around a fixed model, and one where the model itself moves on a tilt-table. Through rotation, a heliodon allows one to take a physical model from sunrise to sunset at any time of day, at any point on Earth. This method of physical modeling can be repeated accurately because the model and light source are securely positioned. It also allows a quick study of different lighting variations. This information can be recorded with a video camera to create presentation-quality movies. Additional quantitative data can be gathered by placing light sensors within the model.

The size of the heliodon table should be proportional to the size of the model. In a typical heliodon, the model is positioned at counter height—approximately 36 inches off the floor. The model’s height can vary, but if it is too low then full rotation will be impossible, and the table itself may cast shadows on the model. A heliodon offers more accuracy than a hand-held model with a sundial; it provides smoother rotation through a typical day. If the model is proportionally correct and the materials used have similar or the same reflectances as the materials being considered for the finished building, you will get accurate light level readings.

Although there are just two types of heliodon, there are different ways to build each type, and there are various online reference resources. Some lighting design and architectural firms will actually build their own, which allows them to customize it for their own use. Lam Partners, for example, is on its fourth-generation heliodon, which incorporates motorized rotation and was designed for transport. Firms that only require occasional access to such a tool can use the daylighting labs at nearby architecture and engineering schools.

SYNTHESIZING DATA AND PROCESS The progression from plan and section diagrams to hand-held model study to heliodon analysis is relatively linear. Project variables will dictate the number of studies required; there is no magic number. Over the course of a project’s development, designers can go back and forth between analysis and design to fine-tune details. “You have to take the most typical conditions, but you also have to work with the complexity of the space,” says Lam associate Justin Brown.

Physical modeling techniques offer many advantages. They are quick, provide a real-time and accurate understanding of how light and architecture interact, and can depict nuances of a material’s qualities. Physical modeling enables qualitative information to be balanced with quantitative results. The immediacy of working with a model and mapping out sun paths gives the designer a sound connection to real-world lighting effects, helping the designer make prudent decisions about daylighting.

Of course, computers are necessary for certain types of calculations, including energy usage and electrical illuminance. Nevertheless, physical modeling, from diagram to heliodon, offers foundational tools that should not be overlooked. “Daylighting, like architecture itself, has to be designed,” Yancey says. “Shaping the architecture, coming up with something from nothing makes the physical models so important; the architecture itself should be the daylighting machine.”