Skyscraper. High-rise. Tall building. Office tower. Call it what you want, there is no denying that this building type plays a critical, ongoing role in architecture’s lexicon. A uniquely American innovation that defines the skylines of New York, Chicago, and so many other cities, the skyscraper is the ultimate expression of modernity in building and inspires architects and engineers to push technical and aesthetic boundaries. But the evolution of this building type is not determined solely by architectural influences. Economics, zoning regulations, cultural expectations, and, yes, light, have played major roles in shaping skyscrapers over time.

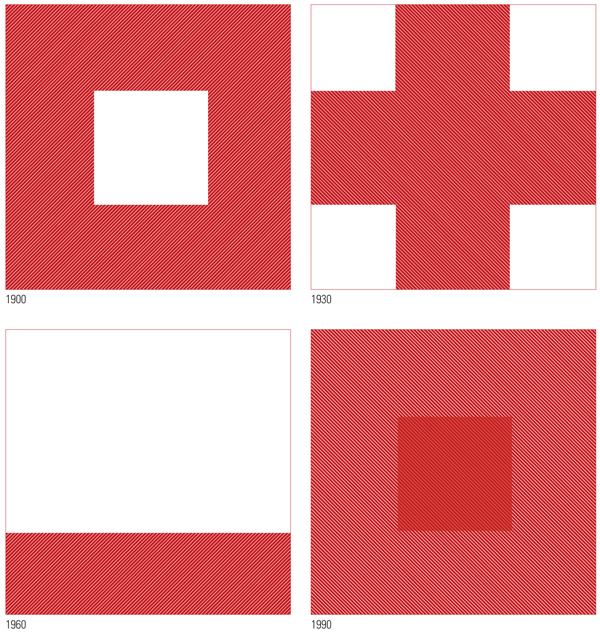

In Form Follows Finance, a seminal work on the topic, Carol Willis, architectural historian and founder and director of the Skyscraper Museum in New York, observes that no matter the variations in building shape or height, one constant is the desire to maximize rentable square footage. For half a century, until the Great Depression put a halt to office construction, the availability of natural light governed office dimensions. “The quality and rentability of office space … depended on large windows and high ceilings that allowed daylight to penetrate as deeply as possible into the interior,” Willis writes. “What the industry called ‘economical depth’ referred to the fact that shallow, better-lit space produced higher revenue than deep and therefore dark interiors.” In other words, architects’ ability to bring natural light into the workplace helped landlords “sell” their buildings.

The advent of air conditioning and fluorescent lighting in the 1940s and ’50s largely removed daylight from the equation, and led to the construction of skyscrapers with tremendously deep floor plates and unpleasant, artificially lit workspaces. The three projects discussed in this issue—the New York Times’ headquarters, the Hearst Tower, and One Bryant Park, all in Manhattan—effectively restore daylight to its rightful place. Together they exemplify a new generation of tall buildings, the product of emerging design trends, architectural and lighting technologies, attitudes toward sustainability, and complexities of building, lighting, and energy codes. Each building responds to a particular set of project criteria and presents a diverse set of solutions, but, taken as a group, the lessons they offer are universal.