Much is at stake in the fast-paced world of high fashion as design houses compete for brand recognition and customer loyalty. In turn, the architectural statement made by each label has become equally as important, conveying the “lifestyle” qualities associated with the brand. One locale that has come to symbolize this fusion of fashionand architecture is the shopping district of Tokyo known as Ginza. In the past decade, a number of major fashion designers haveelicited the talents of notable architects to design their flagship stores including Prada, Dior, and Chanel. Armani is the latest labelto build in the district, soliciting the talents of Italian architect Studio Fuksas. “Ginza is seen as a hotbed of architectural styles,” says Jonathan Speirs, principal of Edinburgh and London-based Speirsand Major Associates (SAM), the firm behind the lighting design at Armani Ginza. “The architectural statement is as important as the fashion statement.”

It is no small endeavor to build a flagship store in Ginza, where real estate is at a premium. When a lot became available, the Armani team acted immediately. From initial design concept to grand opening, the entire process was completed in close to 18 months.

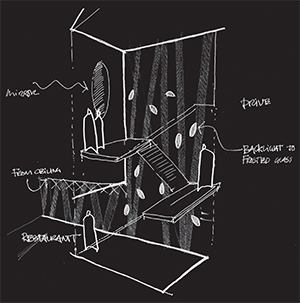

From the outset the goal for this flagship location was not only to create a new image for Armani and to reinvigorate the customer’s understanding of the brand, but also to bring the diverse array of product lines—from clothes to accessories to furniture and home goods—together in one place for a complete shopping experience. The main design focus was the integration of light with the architecture, a particular challenge because, as Speirs explains, “Mr. Armani does not like to see light fixtures.” The design and lighting teams approached their tasks as five separate projects: the façade, a space for the Emporio Armani label, floors for the Giorgio Armani line, a restaurant, and a private bar called Privé. It was extremely important that customers would feel comfortable in the store and actually buy merchandise, not just come to “window shop.” That is why, with the exception of the double-height ground-floor space, all of the retail floors are closed off from windows and views to the outside.

The principal design motif of the project—bamboo stalks and leaves—is the result of Armani’s direct involvement. His selection of this figure reinforces the parallels between his signature understated elegance and the thoughtful refinement of Japanese aesthetics. Working with architects Massimiliano and Doriana Fuksas, the task for Speirs and his firm’s associate director Keith Bradshaw was to “create an experience where light was an integral part of the visual concept.”

Originally the bamboo element, to be represented as a “forest in silhouette,” was intended to cover only the first four stories of the building’s exterior, but Speirs and Bradshaw felt strongly that to fulfill the objectives of integrating the lighting design with the architecture, the motif must be incorporated over the entire length and width of the 12-story façade. But this proved tricky given the site’s proportions; the side face of the corner lot is four times as long as the front face. “The main thing to get right was the façade,” Bradshaw explains. “We needed to create a continuity of light.” Because the designers could not attach fixtures to the exterior of the façade above the fourth floor, they devised a system—a sectional arrangement of glass curtain wall, lighting element, and blackout shades. The stalks are composed of fluorescent and cold cathode tubes while the bamboo leaf utilizes 150 light-emitting diodes (LEDs) encased in an elliptical-like form. To get the desired halo effect around each of the leaves, a white frit pattern is painted onto the blackout shades to exaggerate the shape. A video media server drives the façade’s animation, giving the bamboo the ability to change color. For instance, during cherry blossom season the stalks change from pink to gold with a slight sparkle to give the illusion that they are blowing in the wind.

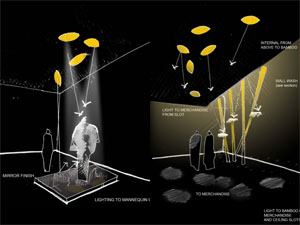

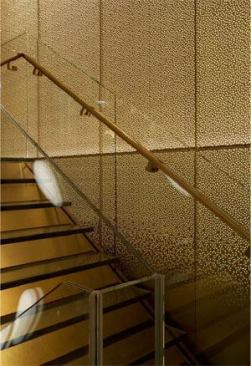

The bamboo motif continues in the interior spaces as well, as the ceiling element for the first three floors, which are devoted to the Giorgio Armani line, the brand’s cornerstone. Custom-shaped ceiling openings, clustered together and lined in gold leaf, have a perimeter fluorescent cove with tapered edges so the light source is never visible. Other displays such as clothes rails are highlighted by a concealed slot system in the ceiling that uses CDMR111 lamps. A gold mesh with the bamboo leaf motif cut into the metal at a very fine scale is sandwiched between glass panels that are positioned throughout the retail area. The ceiling fixtures are connected to a lighting control system that slowly dissolves light onto the panels to create a gentle animation. The “fading” technique coupled with the mesh material renders the panels in and out of view, creating a sophisticated space that is never really static.

By contrast, the Emporio Armani line, housed in two below-grade floors, was designed to be a more active and dynamic space and create an immersive experience. Catering to a younger clientele than the Giorgio Armani label, the distinguishing feature of the space is a wrapper of black steel panels with staggered laser-cuts each 8mm thick. The lighting element is hidden behind the panels, lined with a layer of barisol to conceal the source. An internal reflector made of white MDF pushes the light closer to the center of each panel. To position the lamps correctly, a full-size mock-up was made. “We needed to see the line of the light,” Bradshaw explains. Here, SAM used all fluorescent sources with 0 to 10 volt dimming capabilities. The lamps are grouped together to create an intensity of light, and because some of the lamps are on at 20 percent and others at 100 percent, the modulation of intensity creates a gentle animation.

Custom-built glass elevators backlit floor-to-ceiling with cold and warm white LEDs link the lower-level retail spaces with the ninth and 11th floors, which house the restaurant and private bar, respectively. Color temperature as a whole changes from cool to warm throughout the building, articulating the layers of space as shoppers move from the lower retail floors to the upper floors, where golden tones become more prominent.

“Light is implicit in the design,” Bradshaw says. “The space would not work without the lighting.” Like an abstracted Japanese paper lantern, whose beauty lies in its simplicity of a single gesture, the success of the new Armani Ginza flagship store is the lighting’s integration with the architecture and interiors to convey a series of distinct experiences that culminate in a unified whole.