The building uses a substantial amount of glass, which resulted …

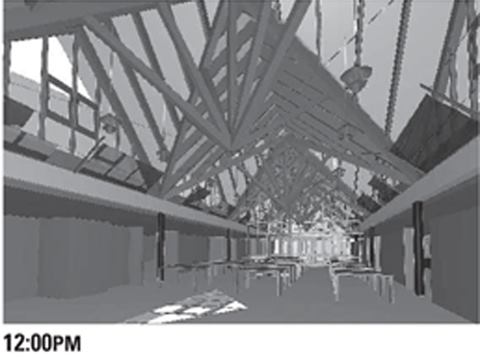

Sami points out that because the human eye physiologically adjusts to the brightest spot in a room and looks at everything in comparison to that, it is important to be aware of a space’s glare ratios. Throughout the day, sensors automatically dim the electric lights when adequate daylight is present. Occupancy sensors ensure that electric lights are not on unnecessarily. The building, especially in the main gallery space, primarily uses indirect electric lighting that is recessed into the architectural structure.

How to illuminate the building at night also was a challenge given the significant amount of glass used in the design. “You have to design any daylit facility to work without daylight,” Nicolow says. “A lot of the [electric] light is directed down on the workspace. We didn’t want it to be too much of a lantern. Outside, we used limited lighting at the parking lot, and the main entry path just has LED wayfinding lights—we don’t light the area but just show where the sidewalk is.” Keeping interior and exterior lighting to a minimum helps to not disturb the facility’s natural surroundings. “You don’t want to have any impact on the wildlife around it,” Butler says.

SUSTAINABLE STRATEGIES The NPS from the beginning wanted a sustainable building design for Twin Creeks. Using the U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating system as a guideline, the project features a host of sustainable design features, with the daylight harvesting analysis having the greatest impact on the overall building design.

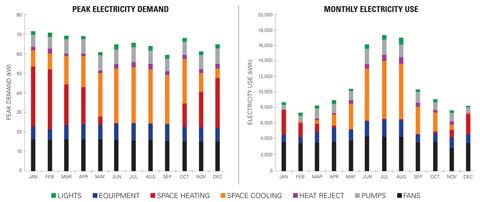

“If you can substitute electric light with daylight, you’re not just reducing electric energy but also reducing the cooling load on the building,” Sami explains. “Daylight is far more efficient in terms of watts per lumen. It’s not a very high-cost item, and it really pays for itself in a short amount of time.” He adds that many architects and lighting designers seem to have the misconception that working toward LEED certification is expensive, but in his experience he has found that LEED typically does not add much to the construction budget—less than 1 percent, he estimates, although he acknowledges that LEED does add to the consultant’s budget.

Nicolow says this project pushed Lord, Aeck & Sargent in terms of qualitative analysis and daylight. The firm began working on Twin Creeks in 2001, and at the time was its first LEED project where LEED was part of the initial design process. The architects originally went about LEED in “the least effective way,” he points out. “We used it like a checklist and kind of went credit by credit exhaustively. While we came out with a nice design in the end, we’ve since transitioned that approach, and we focus on big-picture designs first and then check the points.” This project features a number of sustainable strategies aside from daylight harvesting, such as natural stormwater management, natural ventilation, and site-harvested stone masonry. Butler explains that when the outside temperature is in the “comfort zone,” windows in the clerestories are set to open to naturally ventilate the building. The system is designed to close the windows when the outside temperature is below 45 degrees or above 65 degrees. As for stormwater management, instead of collecting or concentrating the roof and site runoff in pipes, Nicolow says they created “a series of cascading features that filter the runoff and encourage filtration.”

Sami says that going after silver LEED certification helped the design process. “One of the things [LEED] addresses is integrated design, so what you’re doing is you’re creating a design solution that is more advanced, based on people talking to each other.” As a result of the collaborative efforts of all involved, the NPS ended up with a research facility that utilizes a sustainable design heavily focused on daylighting that serves both the needs of the building and its occupants in harmony with its surroundings.

DETAILS

PROJECT | Twin Creeks Science and Education Center, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee

CLIENT | National Park Service

ARCHITECT | Lord, Aeck & Sargent, Atlanta

LIGHTING DESIGNER | Clanton & Associates, Boulder, Colorado

DAYLIGHTING AND ENERGY OPTIMIZATION | RMI/ENSAR Group, Boulder, Colorado

PROJECT SIZE | 15,000 square feet

LIGHTING COSTS | $4.5 million (construction); approximately $50,000 (lighting)

WATTS | .77 watts per square foot

PHOTOGRAPHER | Jonathan Hillyer, Atlanta

DAYLIGHTING STRATEGY | To develop the building section as a reverse-light fixture and introduce daylight into the building while understanding solar positions and designing to control glare.

MANUFACTURER | APPLICATION

ALERA LIGHTING | Office fluorescents

ARTEMIDE | Wall sconces in building corridors

BEGA | Exterior path lights

ELIPTIPAR | Wallwash in classroom

LAURALINE | Exterior wall lights and ornamental pendants in the central bay

LEVITON | Lighting control and dimming

LIGHTOLIER | Track lighting in the office corridor and mapping room

LUMIÈRE | Steplights for the exterior

METALUX | Utility fluorescents

PORTFOLIO | Downlights in the conference room

PRUDENTIAL | Fluorescent strip—direct/indirect in the central bay

SURE-LITES | Emergency and exit lights

WATT STOPPER | Occupancy sensors and timers