Åke E:Son Lindman

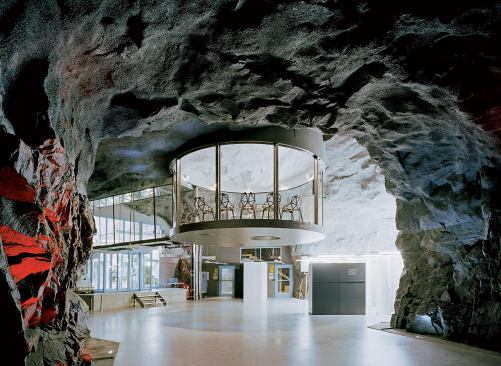

Pionen, a 1,200-square-meter (13,000-square-foot) data center de…

This is where the difference between a colocation data center and an enterprise data center matters. The most-efficient data centers often fall into the latter category, where the building owner not only has input on the facility’s design, but also in its implementation and use. When Google designs a center, Google gets to pick what kind of servers it uses, when to use them, how to cool them, and where the energy comes from. If a company owns the entire center, and all the processing within it, it can be bold in its approach. So, HP can batch its server usage to coincide with down times in demand, and Facebook can run its servers at a slightly higher temperature.

At NY4, these options don’t exist. Poleshuk has his job because he can guarantee his clients three things: first, they can run whatever processes they need at whatever time of day; second, their servers will remain a specific temperature; and third, power will be supplied. When asked about the amount of power NY4 uses, Poleshuk shrugs. “We need these computers,” he says. “We need these centers.”

Shapeshifters

The evolution of data center design remains open-ended. Some architects believe that data centers will become smaller and more modular. They might be little boxes on telephone poles, or they might be mobile and cater to user demand. The advent of cloud computing might result in fewer, larger data centers where processing is pooled or, conversely, it might lead to smaller, scattered data center facilities owned by individual businesses. Colocation centers will then have to find ways to increase the flexibility of their internal structure.

Regardless of the form data centers take, one thing is certain: they will continue to rise in sheer numbers. Two years after NY4’s completion, Equinix is building NY5, a 400,000-square-foot data center, just two doors down.

Despite interacting with them thousands of times each day, communities for the most part will remain oblivious to the existence of the data centers that are quietly multiplying in their backyards. This suits data center owners just fine. For security and safety reasons, they embrace the anonymity of their buildings.

Two hours after first pulling into NY4’s parking lot, I begin my trip home to Brooklyn. At a stop sign, I type my address into my phone. In a split second, a little blue line appears, plotting my route through the Holland Tunnel and across Manhattan. And somewhere in the world, a server deep inside an unmarked building is spinning frantically to process my request.