Unlike conventional photography, the quality of the thermal imager does directly affect results. Not surprisingly, the more expensive cameras—which can cost upward of $60,000, Felleti says—have a greater range and higher resolution, which are essential for documenting mid- to high-rise building façades.

Though thermography can be invaluable to building investigations, “It’s only one tool in our toolbox,” Felleti says. “A camera can pick up anomalies, but without making sure you are 100 percent correct, you are not calibrating the camera—or the operator.” As a result, thermal imaging does not usurp field surveys, water tests, or exploratory openings.

Despite the occasional artifact that appears in thermal images due to noise or poor focus, even skeptics find the visual evidence hard to dispute—particularly if test cuts prove the image interpretation accurate. In Portland, Ore., Wood surveyed a three-story building for defects in the air barrier and cladding. “[The clients] didn’t think there was leaking,” he says. “The thermography showed exactly where it was occurring.” The images helped determine that the design details for the air barrier were inadequate for the contractor to construct a continuous air-barrier system.

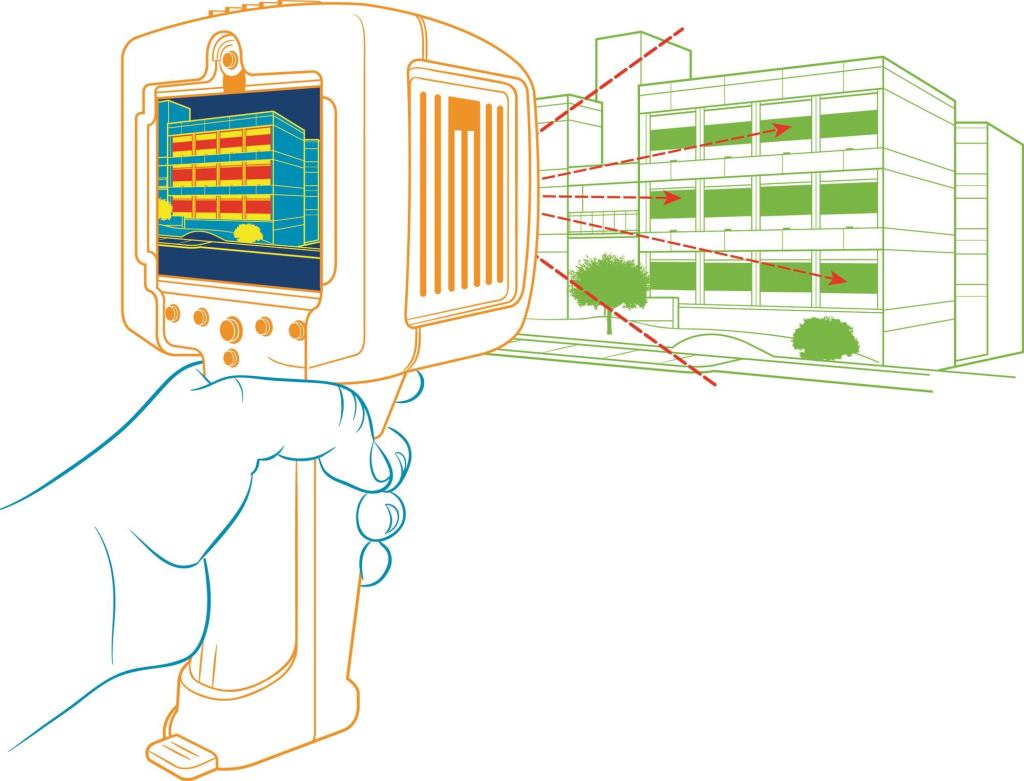

Beyond scanning individual buildings with a handheld camera, citywide thermal imaging is offered through services such as Sagewell. While an average handheld camera can take about one image per 10 seconds, Miettinen says, the high-speed cameras mounted to Sagewell’s cars can capture 250 images per second. “We recently imaged almost 120,000 buildings in five nights,” Miettinen says.

Thermal imaging on a mass scale is beneficial for owners who oversee a large portfolio of buildings, Miettinen says. “The technology is particularly well suited to filtering the high-priority candidates—if [you] want to find the top 20 [percent] or top 5 percent of your buildings where improvements will get you the biggest bang for your buck.”

From the slew of data captured at speeds of up to 45 miles per hour, Sagewell uses a combination of proprietary software and building experts to score the images, using up to 25 building metrics. Because Sagewell only documents what it can see from the street, it often teams with individual thermographers who will subsequently investigate the high-priority buildings thoroughly.

Last winter, Sagewell scanned 100 student townhouses for Bryant University in Rhode Island. Built in the 1970s, the townhouses had endured decades of use without renovations.

Brian Britton, Bryant’s assistant vice president of campus management, says that though the results were not “shockingly revolutionary,” the images confirmed that the townhouses’ windows and doors were drafty and that attic spaces lacked adequate insulation. Renovations, which included updating mechanical systems, were completed on half of the townhouses this summer, with work on the remaining half expected to be completed next year. Bryant anticipated a payback of seven to 10 years. More importantly, Britton says, “We wanted to find an investment that was going to give us a reasonable amount of efficiency—and will work.”

The long-term foresight is refreshing during this time of shrinking capital budgets and action stymied by bureaucracy or litigation. “Just because we’ve identified a building opportunity doesn’t mean owners act on it,” Miettinen says. “It may take us two seconds to drive by your building and take heat loss measurements, but it may take nine months to get the building improved.”

This leaves designers an opportunity to use thermography as more than just a time-saver. They can use it as a visual tool to educate clients on opportunities to improve building performance. Though the technology of thermography is well understood, Miettinen says, “Justifying the internal process in making improvements—that is the part of the story that is still evolving.”

Below is an example of high-tech thermal imaging captured by Sagewell: