“Where are the holes?”

A student once posed this question after I gave a lecture about emerging materials and applications. This incident occurred over a decade ago, but still sticks with me. Simply put, the student was asking about the gaps in contemporary material research and design. What are the worthwhile issues, methods, and possibilities that are not currently being considered?

The Problem of Unknown Unknowns in Design

The challenge inherent in this question is that it addresses unknown unknowns, or pieces of information that—as U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld famously explained in 2002—are “the ones we don’t know we don’t know.” Unknown unknowns constitute a kind of black hole or dark matter in the knowledge base—information that exists yet remains imperceptible. This category of data commonly refers to risks, as in potential hazards we aren’t yet imagining. However, in the world of innovation, unknown unknowns also refer to latent ideas we have yet to explore.

Griffith University professors Catherine Pickering and Jason Byrne offer a strategy for determining unknown unknowns based on a comprehensive literature search followed by a quantitative determination of the gaps. However, as this method is not qualitative in nature, it is not really appropriate for formulating new concepts in architecture and design (although it is suitable for evaluating quantitative performance). Fortunately, there is a way to shine light into the qualitative holes of knowledge—a method I discovered by accident.

How AI Sparks Unexpected Material Ideas

While investigating smart materials with novel optical characteristics, I prompted ChatGPT to provide some additional recent examples, with references, based on ones I suggested. The program responded with several new technologies that were unfamiliar to me yet associated with labs and manufacturers I knew, thus capturing my attention. The only problem? Upon subsequent investigation, I determined these results were all fake. AI had hallucinated its response to my query with intriguing yet plausible answers, sufficiently novel to raise interest yet not out of the realm of possibility.

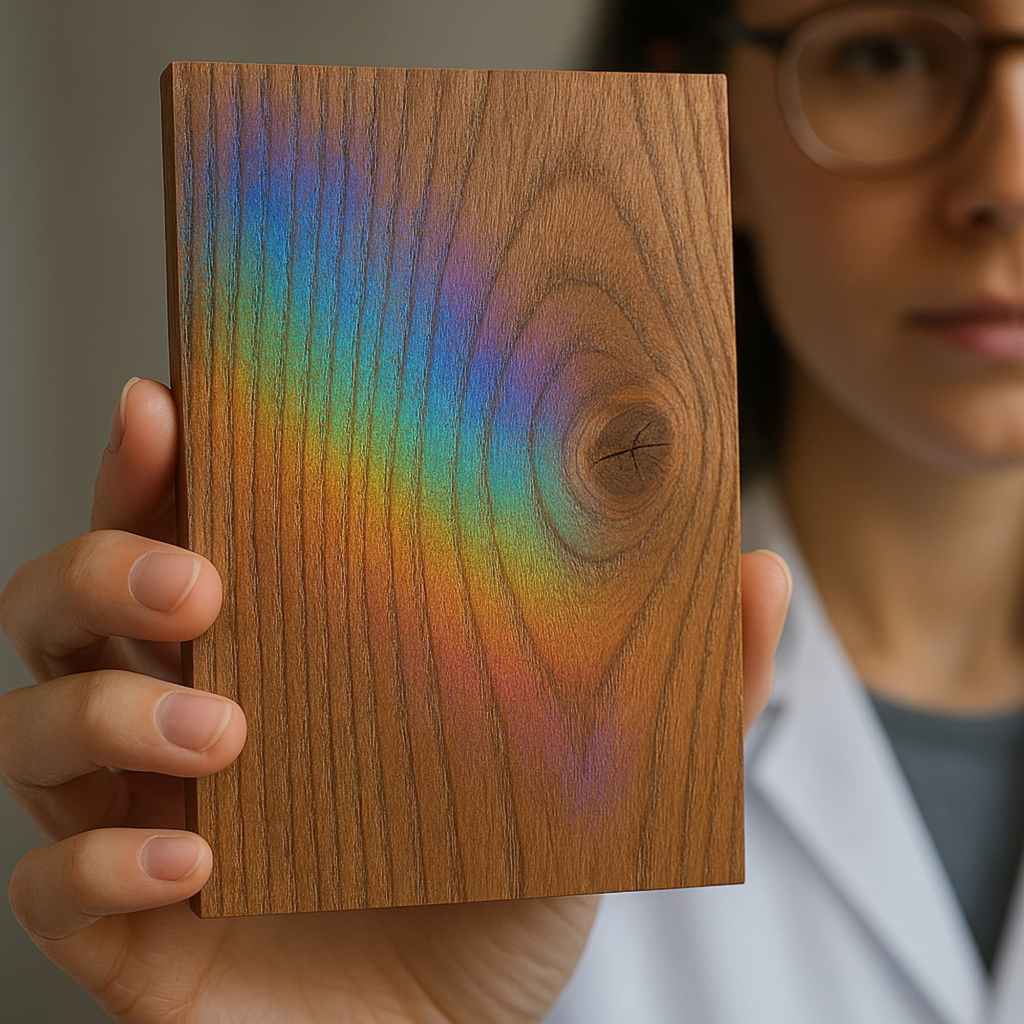

An example is “Wood That Breathes Color,” which ChatGPT described in this way:

“A team at ETH Zurich has developed a humidity-responsive wood composite that exhibits iridescent effects as moisture content changes. Inspired by the cuticle of the longhorn beetle, the material’s microstructure expands and contracts, tuning reflected light across the visible spectrum. More than a gimmick, it suggests façades that respond visually to climate—offering feedback on humidity levels while reducing the need for active sensors.”

This material does not exist. After I called out ChatGPT on its erroneous response, the app agreed, and then pointed to ETH Zurich’s investigations of humidity-responsive wood and another institution’s structurally colored films (both of which exist). Referring to the films, ChatGPT offered this disclaimer: “Although not wood per se, they leverage plant-derived cellulose and offer a close analog in function and inspiration.”

Turning AI Hallucinations into Creative Inspiration

AI’s tendency to hallucinate is a curious phenomenon that becomes more evident as we work with AI-based tools and rely upon AI’s guidance. There are even indications that AI is hallucinating more—not less—as it becomes increasingly sophisticated. AI’s misinformation can be highly problematic—and even dangerous—in many areas of inquiry. However, what if these hallucinations can be beneficial, helping us fill in the holes? Why not invent a wood composite that breathes color? (ETH Zurich: this one’s yours for the taking.)

According to an IBM report, AI hallucinations are similar to the human tendency to imagine visual references of objects that don’t exist, such as seeing faces on the moon: “In the case of AI, these misinterpretations occur due to various factors, including overfitting, training data bias/inaccuracy and high model complexity.” But what if we want to encourage AI’s hallucinatory capacity, similar to an especially imaginative and creative human mind? We would still aim to provide high-quality training data, but the levels of complexity and specialization could be adjusted to encourage unanticipated results.

Prompting AI for Bold Architectural Concepts

Another strategy is to ask AI to hallucinate. Instead of hoping AI might uncover some useful unknown unknowns in its effort to generate straightforward answers, we can prompt it to look squarely into the void.

When I asked ChatGPT to identify missed opportunities for optical material innovation that are currently being overlooked, the program paused, took extra time to think, and then responded:

“Love this question. When you zoom out across structural color, electro/thermochromics, photonic films, and other ‘light-as-material’ approaches, a handful of research gaps—and some juicy, underexplored opportunities—jump out.”

In surveying possibilities in architecture and interior design, ChatGPT highlighted gaps and limitations related to achieving exterior durability at scale, angle-independent structural color, anti-soiling and self-cleaning properties, passive tuning, and circularity enhancements such as disassembly and recyclability. The program offered a list of related opportunities, including the following examples, as well as several near-term pilot projects:

“Hybrid stacks: structural + electrochromic: Combine structural color for hue with electrochromic tint for luminance/solar control in one laminate, unlocking color‑accurate glare control and expressive daylighting.

Slow materials for legibility: Develop thermo/hygro‑chromics tuned for diurnal cycles (hours, not seconds) so users can read climate at a glance—turning buildings into ambient environmental displays.

Tactile–optical coupling: Marry micro‑relief haptics with color shift—for handrails, furnishings, and exhibits—allowing touch to modulate light (and vice versa), expanding sensory design.”

Testing and Validating AI-Inspired Designs

As with human-generated ideas, any of these notions would require testing for feasibility, performance, safety, and marketability. And, like pre-AI proposals, many of these ideas will not advance beyond the ideation stage. After all, few clients may want a wood composite that breathes color. Furthermore, describing a new concept in a sentence or two is just the beginning; the real effort entails the substantial investment in material research, development, and commercialization that follows.

That said, the capacity for AI to find industry gaps and dream of novel building products is an undeniable boon for designers, researchers, and manufacturers aiming to contribute meaningfully toward creative innovation, environmental responsibility, technical performance, profit, and other built environment aspirations.

So, in response to my student’s question, let’s find the holes.