Since the first modern industrial processes replaced manual labor with machines, humans have been concerned about the potential effects of technological automation at scale. Today, this apprehension is associated with a certain backwardness or resistance to progress, and those espousing such a view are often dubbed Luddites. However, this is a misnomer and a generalization. Understanding why requires a quick dip into the annals of labor history: The term “Luddite” comes from the nickname given to a group of textile-weavers-turned-labor-activists who, in the early 19th century, launched a regional uprising in northwest England to protest the use of power looms and other machinery supplanting wage-earning humans in mills, and the substitution of their handiwork with a cheap alternative. The Luddites were artisans and the rise of the machines threatened their craft. “[C]ontrary to their depiction in popular culture, [Luddites] weren’t afraid of the technology itself,” explains journalist Brian Merchant for Vice. “They were acutely aware that the work they had been trained to do by hand, the craft they had refined over the course of their entire lives, was about to be made obsolete by a machine. A machine that would do a worse job, but for much cheaper.”

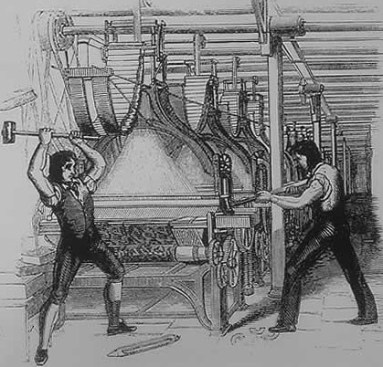

Luddites, also called frame-breakers, smash a loom in protest of the encroachment of new technologies on traditional craft.

Though much has changed since the early 1800s, trepidation over automation, which now encompasses data access and communication in addition to manufacturing, persists. Automation, robotics, and artificial intelligence are poised to “replace tens of millions of workers,” writes author Jeremy Rifkin in The Zero Marginal Cost Society (St. Martin’s Press, 2014). Yet the balance between jobs lost and jobs gained due to new technology is unclear, according to an August 2015 column in The Economist, and if the past is any guide, today’s predictions of a robot-driven future workforce may be wildly off the mark. And so rather than hold creativity and automation in opposition, architecture, engineering, and construction professionals should seize this critical moment for bringing automation into creative practice. Because unlike the steel and wood machines targeted by the Luddites of yore, today’s technologies are much more difficult to destroy.

A November 2015 report from global consulting firm McKinsey explains that creative tasks are largely immune from automation because “capabilities such as creativity and sensing emotions are core to the human experience.” Organically incorporating creativity into one’s work, in other words, is what separates us humans from the machines. Yet workers in the U.S. generally spend very little time on creative tasks, with only a sliver (roughly 4 percent) of work activities across the nation’s economy requiring “creativity at a median level of human performance,” according to the report. Adding a base layer of automation could help to maximize the creative potential of different kinds of work, the authors explain, by enabling workers to focus their attention on the more engaging aspects of a larger task. For example, the authors write, “interior designers could spend less time taking measurements, developing illustrations, and ordering materials, and more time developing innovative design concepts based on clients’ desires.” Although this description seems misinformed (interior designers often cultivate innovative design concepts while developing illustrations, for example), their general point about minimizing drudgery is welcome.

Automation as Creative Practice

This binary

view—positioning creativity and automation in opposition—fails to address the

ways in which technologically savvy designers and manufacturers today are

developing automation as a creative practice.

KieranTimberlake, in Philadelphia, exemplifies such an approach from an architectural perspective. The office’s research activities include the development of custom hardware and software for building-climate monitoring and environmental analysis. The firm also routinely generates bespoke simulation tools and building fabrication methods, providing architects with increased granular control over the design process. According to firm partner and research director Billie Faircloth, AIA, KieranTimberlake is interested in “accessing and aligning data in meaningful ways.”

The investment

provides returns in at least two ways. First, the design process is enhanced with information typically beyond the reach of architects. For

example, the firm’s Wireless Sensor Network (WSN) provides real-time,

broad-spectrum climate data that facilitates the development of environmentally

responsive buildings. Architects regularly make design decisions based on

regional climate information, but the WSN enables them to make more informed

choices using rapid feedback from a range of real conditions. This method

enables the capacity for predictive modeling, demonstrating important

connections between form and performance, and providing increased risk

tolerance related to weathering and aging.

Another benefit

concerns the bottom line. The firm’s innovative prefabrication methods, for example, ensure quality while cutting

costs. Among the prefab approaches are new construction assembly systems for

their Loblolly and Cellophane houses, in Maryland and New York,

respectively, as well as the stacked-module method seen in the

KTLH 1.5 house in Newport Beach, Calif., and the Belles Townhomes, in San

Francisco. Inspired

by the firm founders’ 2003 manifesto, Refabricating

Architecture: How Manufacturing Methodologies are Poised to Transform Building

Construction (McGraw-Hill Professional, November

2003), the

expertise derived from years of off-site fabrication analysis is paying

dividends in current and future work—including a project to provide inexpensive,

rapid-construction housing in India.

Creative Manufacturing

Creative automation is also playing out in manufacturing. Product

manufacturers are beginning to resemble information technology firms. And as

the burgeoning Internet of Things brings sensors and network connectivity at a

more accessible price point, manufacturers are able to incorporate them into

their products, which increasingly exhibit new capacities for monitoring and

response. Successful manufacturers are exploiting this shift by focusing on

creating products that are designed to perform a service, such as home-monitoring

systems or machines that order parts themselves when needed.

This transformation in product function is resulting in the

development of systems of interconnected services and applications, or platforms.

For example, Santa Clara, Calif.–based startup Gooee

offers a cloud-based operating

platform for enterprise-level LED lighting in residential, commercial, retail,

hospitality, and industrial applications. This platform provides real-time

sensing, control, and communications that allow lighting fixtures to perform functions such as occupancy detection, measuring ambient temperature, reporting metering problems, and even triggering alarms in the case

of a fire. This is possible due to recent developments around LED technology that allow such functions to be built with the light source into the LED

board. Sophisticated platforms like Gooee’s join a growing number of similar services already active in the lighting space to provide a novel means of monitoring building conditions, enhanced connectivity

to manufacturing processes, and automated control of energy consumption.

These examples challenge conventional design and manufacturing business models, and they open up opportunities for licensing and partnerships with manufacturers. For one thing, the development of custom software and networking tools is beyond the expertise of most architects and product manufacturers, who are already inundated with increasingly demanding codes, regulations, and material processes. Additionally, the development of continually responsive platforms is inherently more complex than the former cradle-to-grave paradigm, which focused on the phase prior to customer purchase or move-in.

Yet companies’ success will be tied to taking on these

challenges, and the most effective firms will come to dominate their competitors

through the insightful use of such technologies. After all, success will no

longer be tied solely to making the best products but instead will require creating premier

digital services in connection with those products. This is likely to be the case

for many creative industries, from lighting designers and manufacturers to architecture

firms. The key, therefore, is not avoiding automation but figuring out how to

embrace it—creatively.