It only took a matter of minutes for a tsunami wave to reduce Onagawa

Station to a pile of rubble. The one-story, tile-roofed train station in Miyagi

Prefecture, Japan, was just 50 miles from the epicenter of the magnitude-8.9 earthquake

that sent a series of 10- to 20-foot-high waves crashing into Japan’s main

island of Honshu on March 11, 2011. The structure was one of 127,000 buildings

that were completely destroyed, with another 1 million reporting some damage.

More than 15,000 people lost their lives.

Four years later, almost to the date, a new train station stands in Onagawa, this one designed by Shigeru Ban, Hon. FAIA. The airy three-story, 900-square-meter

(9,682-square-foot) structure—the eastern terminus of the Ishinomaki Line, which

runs from Kogota Station, in Misato, to Onagawa on the east coast—was sited about

500 feet inland from the original building footprint.

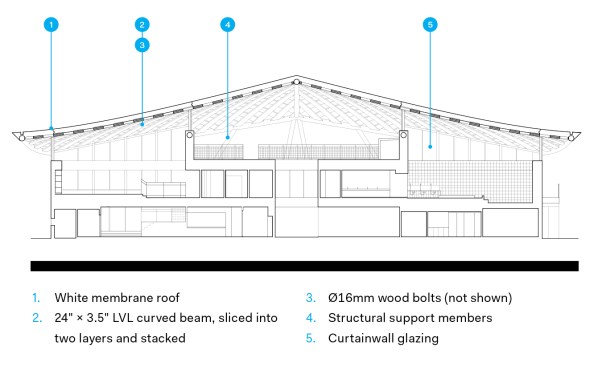

Roof section

Topped with a gently sloped, tensile-membrane roof inspired by the outstretched wings of a seabird, the cedar-and-steel-pipe-beam

structure serves as a symbol of the community’s resilience. At night, the illuminated

station casts a warm glow through the translucent white membrane, “symbolizing a reconstruction of the town from the

disaster,” says Yasunori Harano, project architect for Shigeru Ban Architects.

Hiroyuki Hirai

The underside of the lattice structure is visible from the public plaza and esplanade that have been added to the station, which also features white tile painted with wilderness scenes in the spa.

The taut roof form is supported by a wooden lattice, a

signature of Ban’s work. The lattice members are left exposed in the station’s

interior spaces, which include a public bathhouse that had been originally housed

in a separate facility that was also destroyed by the tsunami, as well as a

public plaza and esplanade.

The lattice is made of laminated veneer lumber (LVL) arches constructed from Japanese larch (Larix kaempferi),

which is native to the country and appears in everything from furniture to

boats to utility poles. Harano and the project team needed to warp the 2-foot-wide LVL beams to

achieve the desired curvature and roof height, but at 90 millimeters (3.5 inches)

thick, the lumber wasn’t bending properly. The designers worked with local

timber subcontractor Key-Tec Co. to slice the LVL lengthwise and warp each half separately before layering them back together during

the construction.

This created a new challenge. The stacked LVL layers needed to be connected with custom wooden

bolts, but to drill the bolt holes after the wood was warped would “take time

and lack in accuracy,” Ban says. Subsequently Harano’s team created a 3D model

of the lattice structure that included the final location of each bolt in the curved

LVL beams to determine where to drill the 16-millimeter-diameter holes in the

pre-bent wood. The arches were then transported to the construction site, where

they were assembled by the contractor.

Hiroyuki Hirai

The wooden bolt heads are arranged in alternating geometric patterns—specifically an eight-studded circle and a square with inverted corners.

The final roof structure features 76 crisscrossing arches, with

many spanning more than 55 feet. Each arch intersection in the lattice is secured

with the same custom bolts that connect the stacked LVL layers. The wooden bolt

heads, which are left visible and slightly paler in tone than the LVL, are

arranged in alternating geometric patterns—specifically an eight-studded circle

and a square with inverted corners.

The building’s completion earlier this year coincided with the

reopening of the Inishomaki Line, reconnecting the seaside town to the rest of

the country. By combining the train terminal, a bathhouse, retail spaces, and a

third-floor platform from which visitors can admire Onagawa Bay, Ban hopes the

station will serve as a gathering place for the community and a symbol of its resilience and recovery.