Project Description

Surely no contemporary building has had a more unlikely trajectory over

the last two decades than the Kunsthal in Rotterdam. It is both an

emblem of the rise of arguably the world’s most influential living

architect and the setting for one of the most spectacular art-heists in

modern memory. Action, adventure, architectural history—this project has

it all. And now it has entered a new chapter quietly and

inconspicuously—just how the architect would like it.

Completed in 1992, the Kunsthal was one of the first buildings to

emerge from the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), cofounded by

Dutch design mastermind Rem Koolhaas, Hon. FAIA. Koolhaas had come to

architecture after years as a would-be filmmaker and journalist; his

1978 book, Delirious New York, broke like a thunderclap over

the profession, announcing the arrival of a wildcat iconoclast who’d set

his face against modernist pieties and postmodernist cheek. Until the

late ’80s, OMA’s work had comprised mostly speculative and unbuilt—or

unbuildable—projects, including a contribution to the 1980 Venice

Biennale’s Strada Novissima installation and a failed proposal for

Paris’s Parc de la Villette.

The Kunsthal could thus be considered the first project to translate

Koolhaas’s hyperactive functionalism and irreverent regard for form into

architecture. Squat and square, the structure is divided into two

volumes. One features an upper course of stone cladding above a lower

register of glass, in alternating straight and angled strips that are

punctuated by regular vertical mullions. The other features a fully

glazed enclosure topped by a Miesian, flat, steel roof.

With Rotterdam’s existing art museums freighted with their own

permanent collections, the municipal government commissioned the project

to create a space that could host temporary exhibitions, film

screenings, art classes, and dining. Koolhaas seized the mixed program

with gusto, creating a layered sequence of spaces, including a

semi-outdoor café, auditorium, and exhibition halls, all of which

overlapped each other in a determinedly anti-hierarchical jumble.

OMA has certainly evolved since then, but signature elements in the

Kunsthal have appeared again and again, in projects from the Casa da

Musica in Porto, Portugal, to the Seattle Public Library. As the firm’s

breakthrough building, the Kunsthal had surely secured a place in

history. Unfortunately, it’s not the only reason why the building is

famous.

In October 2012, as part of the institution’s 20th anniversary, the

Kunsthal presented a show of major 19th- and 20th-century paintings from

the Triton Foundation collection. On Oct. 16, two thieves broke into

the rear entrance of the building in the early morning, triggering the

alarm but escaping with seven masterpieces by the likes of Picasso and

Matisse.

The robbery was one of the most costly to hit the art world in a long

time: The combined insurance value topped $23.8 million, and the resale

price would have been even higher. But with the pieces logged in the Art

Loss Register, hindering their sale on the international market, the

thieves fled with the loot to their native Romania, where one of them

made a fateful decision: He entrusted the paintings to his mother, who

then allegedly burned them in her home fireplace to hide her son’s

guilt.

The thieves and conspirator pled guilty last year and were sentenced to

prison. But with its security system exposed as a near total dud, the

Kunsthal has not quite recovered from the publicity. As part of its

efforts to reinvent itself, the institution completed its first major

renovation in January, with Koolhaas and company back at the helm.

OMA partner Ellen van Loon, who led the renovation, wasn’t with the

firm during the Kunsthal’s original construction, but she certainly knew

it well. “It’s a project that’s hard to miss,” van Loon says. “At the

time it was built, it was quite a progressive project in Holland, and it

made a lot of people discuss architecture. There weren’t any architects

who didn’t notice it.”

In returning to a building that was so central to OMA’s early days, you

might expect a certain cringe factor—like looking at your own baby

pictures—but van Loon and her team were fairly pleased by how well the

building had weathered. “Our conclusion was that the building worked

better than anyone thought, from day one,” she says. “Materials that

people said would only wear five years would wear 20 or longer.”

That said, the building needed a tune-up, and not just to its security

system. Sustainable design was in its infancy when the initial scheme

was completed, and higher performance standards have since become de

rigueur for OMA and the profession at large. Updates to the building

envelope and M/E/P systems, which will slip by unnoticed by most

visitors, will reduce the museum’s heating bill by an estimated 30

percent, and the energy consumed by its electrical and HVAC systems by

28 percent.

Achieving these improvements without distorting the essence and

experience of the Kunsthal required strategic moves guided by the

subtlest of design changes. High-performance double-glazing replaced the

wraparound windows. Fluorescent lamps and LEDs have partially replaced

conventional sources in the museum’s distinctive lighting plan. Low-flow

fixtures outfit the reconfigured bathrooms, and a heat recovery system

salvages thermal energy circulating through the building. Humidity and

carbon dioxide monitoring systems maintain the physical comfort of

visitors.

The central museum’s open plan also experienced some tweaks. The

“continuous routing,” as van Loon describes it, meant that large swathes

of the building had to be conditioned even when they weren’t in use.

New glass partitions allow heating and cooling to be delivered to areas

where needed, and shut off where they’re not.

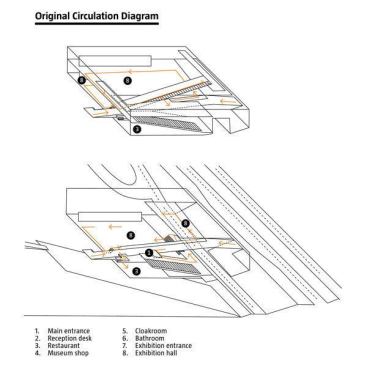

Next on the docket was the Kunsthal’s programmatic layout. “The

building is visited by many more people than we originally planned,” van

Loon says. Though the renovation brief didn’t specify an expansion of

the approximately 70,000-square-foot interior, the existing envelope

could accommodate more museumgoers. The building’s main entrance was

relocated to what was formerly the entrance to the restaurant; now

guests are steered through the café and museum shop, around a cloakroom

and restrooms, and then up and down the iconic ramps.

Along with minor shifts and partitions in the interior plan and a

revised wayfinding and signage system, the rearrangement allows

different parts of the building to be used simultaneously and discretely

by different users. This reflects in part a major shift in Dutch

society since the early ’90s: While the Kunsthal was once almost

exclusively government funded, it now has to rent out its spaces to

outside groups to generate revenue. “We basically made the building more

multifunctional,” van Loon says—an operation that is very much in line

with OMA’s functionalist philosophy.

As for security?…?well, let’s just say major changes have been made.

With the top-to-bottom refurbishment of Amsterdam’s massive Rijksmuseum

finished just last year, a lot of experts in art protection are rattling

around the Netherlands these days. OMA found a local consultant—they

declined to name which—to help ensure that the 2012 incident does not

repeat. Neither van Loon, nor anyone else, can discuss the new security

measures. “It’s confidential,” she says. Understandable.

When it comes to iconic buildings, the potential to over-tinker with

the original concept always hangs above the heads of those who are

overseeing the renovation. The Kunsthal, though, had the good fortune to

be operated upon by its own progenitors, who—as parents often

do—combined a special reverence for their creation with a frankness in

assessing its flaws.

Looking back, van Loon does see that the initial scheme left room for

improvement—but not in the way of making the museum more of a guarded

citadel. If anything, she says, the renovation has opened up the

building and made it even more of an OMA project: active, stimulating,

and full of surprises and unexpected maneuvers. “What we’ve done is

[added] these acupunctural interventions on the project to make it work

better functionally,” she says. “It’s just more flexible now, without

losing the original idea.” —Ian Volner