Project Description

Text by Joseph Giovannini

In his Yale University lectures, architecture

historian Vincent Scully used to extoll Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum

for busting up the New York grid with a geometry that breaks the phalanx of

apartment buildings along Fifth Avenue: The building’s spiraling drum spins in

a vortex that breaks apart Manhattan’s tight parade of buildings. America’s

champion of organic architecture, a declared enemy of the box, released the grip

of the orthogonal city.

Two avenues east, on Park Avenue South, and a half century later, Christian de

Portzamparc, Hon. FAIA, similarly disrupted the constricting grid of the city,

but with another geometry. The French architect deployed an elongated 40-story

prism whose crystalline forms establish a zone of their own that open up the street

wall, breaking free of the dense pack of right-angled, brick-faced buildings.

As with the Guggenheim, 400 Park Avenue South disrupts the urban pack with an

exceptional, and exceptionally beautiful, surprise: a tall, sheer rock crystal

of glass. The entire shaft of the elegant new landmark is iconic, not just the

crown. The Prism, as it is called, contributes not just to the skyline but to

the bodyline of buildings, Yosemite’s West Face transposed to Manhattan.

For

all its éclat on its corner at Park Avenue and East 28th Street, de Portzamparc

says the $400 million building grew from the inside out. Manhattan is, of

course, famous for the spectacular views from its skyscrapers, but the dirty

little secret of many buildings is that apartments sharing party walls have no

windows, and those facing rear have no views other than nearby buildings just

on the other side of mean backyard setbacks: residents live with their blinds

drawn for privacy.

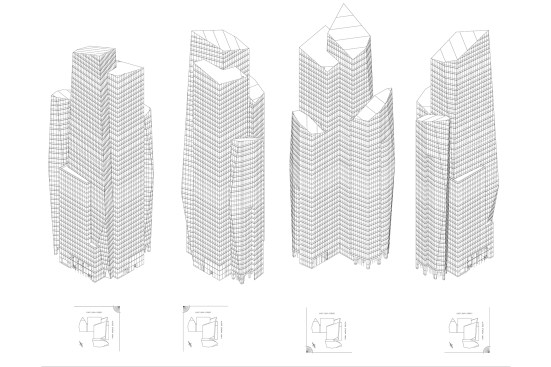

Portzamparc

configured an L-shaped building to match the shape of the site, but he kept the

ends clear of the adjoining buildings, where he extruded pavilions with windows

oblique to the street. The angled windows capture longer views and more light. The

architect configured the two legs of the L as intersecting volumes, and he

detailed the joints between the intersecting volumes and adjacent pavilions

with deep reveals whose shadows separate, and profile, the adjacent

prisms.

Rather

than stepping back the mass to comply with zoning laws intended to bring light

down to the street, de Portzamparc simply inclined the leading edges of the prisms

to open a path of travel for sunlight. “Instead of using terraced setbacks to

respond to code, I fragmented and angled the façade,” says the architect. He

detailed the tower so that its spandrels and awning windows form continuous

surfaces whose visual unity supports the profile of each shard, highlighting

their shapes and the separation between them. The eye looks to the knife-like

corners and finds that the blades are crisp and sharp.

De Portzamparc designed the tower in

2003, building on the critical and popular success of his previous work, the

LVMH Tower, completed in 1999 in Manhattan, where he first fragmented a street façade

as a way of satisfying code setback requirements. Averaging the push and pull

of the façade’s fragments achieves the same degree of slope as terraced

setbacks. On Park Avenue South, he proved that the same idea applies at a much

larger scale.

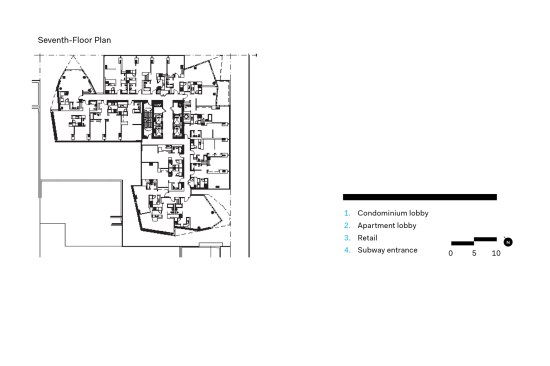

In a

feedback loop, the irregularity of the perimeter, caused by the search for

views and light, rebounded back to the floor plans, where the multiplicity of

privileged corners in the distinct volumes created opportunities for unique

apartment configurations: the building is not a box, nor are the apartments. New

York–based Handel Architects, architect of record, designed the rental

apartments on the lower 22 floors; Stephen Alton Architect, also a local firm,

did the condominiums above. The architects were able to leverage the

irregularity of the perimeter into highly differentiated plans that escape the

cookie-cutter predictability of cuboidal buildings. Sociologically, the variety

of plans—from studios to four bedrooms, varying in size as the leading edges

lean—guarantees a varied population among the renters and condominium owners.

The basement in the tower is lavishly equipped with a large gym, 60-foot lap

pool, screening room, community room, playroom, kitchen, and conference room. A

store along Park Avenue and a restaurant along East 28th Street, with

a subway entrance in between, will animate the street when completed.

After

a dozen years of delay, few changes were made. “I was gratified that the design

remained valid and dynamic after so long,” says de Portzamparc. His

interpretation of a complex, angular language that started appearing

internationally in the 1980s remains fresh because of the clarity of an idea

and a form expressed so robustly. The fragmented shapes and tapering lines deny

the mass of what appears to be an explosion of crystal. The angular tower, with

the elegantly detailed curtain wall, startles the eye in the predictable

right-angled world around it. 400 Park Avenue South is exceptional within in

its context, and exceptional within its tradition as an uncompromised

statement.

During planning commission hearings about zoning changes for the project, a former

city council member, Margarita Lopez, said she happened to be reading Dante,

and in an unexpected paean to the building, she said she liked the way the

sunlight would follow the architectural lines into the Stygian depths of the

subway station at the foot of the tower. Conversely, in the upward direction,

the oblique lines, some converging, force perspective, creating the perceptual

illusion of accelerated form: the building is visually dynamic because it plays

perspectival tricks as old as the Renaissance, but in a vertical rather than

horizontal direction.

The

various community and city agencies voted in favor of the project, even giving

it bonus square footage, because members felt it made a positive contribution

to the neighborhood and the skyline. Their approvals proved right.

Cost: $400 million