Project Description

“Can architecture serve as a way to reconnect parts of the city or

enhance human experience?” asks architect Michel Rojkind, founder of

Mexico City–based Rojkind Arquitectos.

The question is ambitious, even a little outsized, considering that

we’ve sat down over coffee to discuss the firm’s remodel of an outpost

of Liverpool, a Mexican department store. But Rojkind is sincere and determined to create designs that give back to the community.

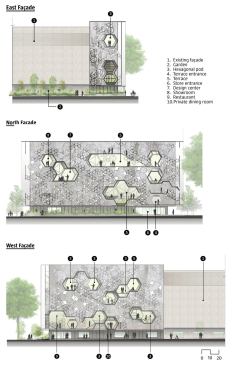

Located on the southern part of Avenida de los Insurgentes,

one of Mexico City’s longest streets, the original Liverpool building

followed a typical big-box strategy: A blank stucco wall facing the busy

street, with all the retail activity turned inward. Over the years, the

site’s meager outdoor plaza was encroached upon by additions or left

unmaintained. When a new metro station opened in 2012 on a corner of the

site, bringing increased pedestrian traffic, it was clear that a beige

façade had no chance of enticing people into the store or contributing

to the urban environment.

“Where city planning failed, can we do something with architecture?”

Rojkind asks. With the original Liverpool store, the failure was one of

imagination, and the store was desperately in need of an identity that

would engage the street. The “something” that Rojkind and his team

developed is a habitable façade that wraps the old department store in a

honeycomb of eye-catching design and activity.

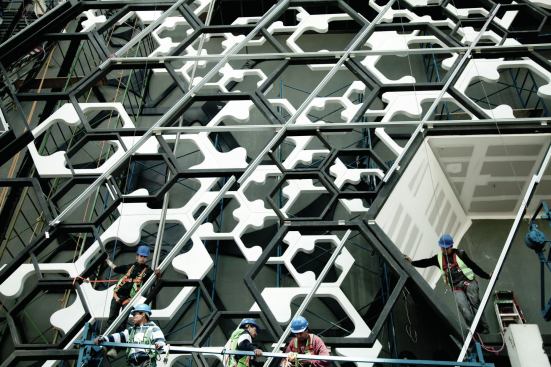

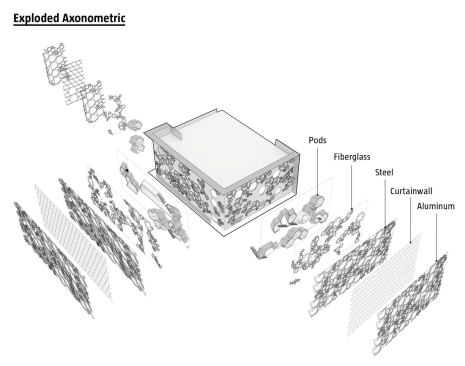

The three-layered façade system—what appears to the passerby as merely a

pattern of overlapping, glazed hexagons—covers the top five floors of

the six-story building. At roughly 10 feet deep, the façade extension

adds 8,800 square feet of floor space to the store and opens up the

inside retail departments to the urban environment. Shoppers enter the

space at ground level, traverse the traditional department store layout,

and then, surprisingly, re-emerge into daylight at the perimeter, where

they can occupy the room-sized hexagons and navigate between them via a

series of stairways and ramps. A square, hollow-section steel structure

attaches to the building’s existing steel beams and supports the

hexagonal layers of black fiberglass, white steel plate, and matte gray

aluminum. The final layer is a glass-and-aluminum curtainwall for

enclosure. During the day, the playful patterning on the façade unifies

the street corner, offering a few glimpses of its depth. At night,

Rojkind’s design turns the department store inside out. The façade

transforms into filigree accented with neon, the interior departments

showcased through the hexagonal vitrines.

In his office in the Mexico City neighborhood of Condesa, Rojkind shows

off the concept models; each is a lacy, laser-cut affair. There’s even a

nearly full-size mock-up of one of the hexagonal pods—a fabrication

test of complex geometries. The aesthetic is undeniably computational,

but Mexico is still a place of craftsmanship, with a long metalwork

tradition. Although the plan was to use a CNC router to cut out the

hexagons for the façade, in a city where labor is plentiful, it was

actually more cost effective to cut each piece by hand—all 1,193 of

them. The result is a building that is equal parts digital and analog.

With the flagship at Insurgentes, Liverpool and Rojkind are betting on a

simple axiom: Design adds value. Liverpool was founded in the latter

half of the 19th century and it reaches a broad market without being a

discount retailer. Rojkind Arquitectos first worked with the store’s

parent company, El Puerto de Liverpool, on the design for Liverpool Interlomas in suburban Huixquilucan de Degollado, Mexico.

There, they created a dynamic double-skin façade, but it was the roof

terrace and event space that proved the real success: Rooftop spectacles

of the gastronomic and fashion persuasion allow the client to extend

its hours of operation late into weekend evenings. According to the

client, the new space accounts for a 30 percent increase in store

revenue, and it was this proof of concept that convinced Liverpool to

take a further risk with the façade extension in Mexico City.

At Insurgentes, the formal qualities of the façade recall motifs and

techniques drawn from the global architecture marketplace, but Rojkind’s

scheme aims to create an experience unique to this urban environment

through temporary programs that reflect the store brand. In drawings of

the building, the voids in the façade are described generically: booth,

terrace, or showroom. Ask Rojkind and he paints a more vibrant picture: a

local radio station spinning records, a high-tech co-working space, a

cooking demonstration, or a yoga class. The opportunities are endless,

the trick is figuring out how to and who should curate them. In this

case, the architects are incredibly involved in the populating of the

space, proving that their job was not complete once the final punch-list

items were finalized.

If any architect were to contribute in such a way, Rojkind is

particularly well-suited: Having spent a decade as a rockstar drummer in

Mexico, his interests extend beyond architecture and into food, art,

and music. Those proclivities are what led him to convince the Liverpool

client to ditch the mannequins and let people fill the show windows in

the first place. He struggles with the idea that architecture’s

influence is primarily limited to the building itself, and his work

tends to blend design with culture and strategic branding. “Architecture

and the profession are evolving,” he says. “Architecture is the

hardware, but who designs the software—the experience?” At Insurgentes,

the architects are lending a helping hand. —Mimi Zeiger