Project Description

Santiago Calatrava, FAIA, has had a tough couple of years.

What should have been a glamorous and career-capping commission for the 63-year-old Spanish architect, the new transit hub at the rebuilt World Trade Center,

has instead been plagued by extensive delays and massive budget

overruns. In the end, it will likely take roughly twice as long to build

and cost twice as much ($4 billion versus $2 billion) as originally

planned. In the process, it’s become a symbol of larger bureaucratic

problems at Ground Zero, a money pit half-buried next door to the National September 11 Memorial and Museum.

Meanwhile, what had been a steady trickle of complaints about

Calatrava’s high fees and complicated, tough-to-build designs, which

often feature elaborate moving parts, turned suddenly into a flood. A

front-page article in The New York Times last September slammed Calatrava as an aloof, uncaring “star architect” who charges absurdly high fees—$127 million for his City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia, Spain, alone—and whose all-white buildings often crack, leak, or buckle.

It went on to mention a Spanish website devoted to criticizing the

architect, helpfully pointing out that its URL loosely translates to the

phrase “Calatrava bleeds you dry,” before concluding that “other cities

may be reluctant to hire Mr. Calatrava again.”

Given that shift in Calatrava’s professional persona—before the World

Trade Center job, after all, he was more often cast in the role of civic

savior—I have to admit that I paused and laughed out loud right into

the soupy central Florida afternoon when, walking toward the front door

of the architect’s latest American project, the Innovation, Science and

Technology Building (IST) at the new campus of Florida Polytechnic University

near Orlando, I saw a white sign with red letters installed near one of

the ponds that Calatrava designed along the building’s southern edge.

The sign showed a green animal with snapping jaws inside a circle with a

line through it. Below that, in capital letters, were the words DO NOT

FEED THE ALLIGATORS.

It seemed an admonition as much to Calatrava as to the students who

began using the building at the end of August. Do not give your critics

any more ammunition. Do not produce another pricey, preening,

overcomplicated, and underperforming piece of architecture. Do not

leave another client fuming and ready to complain, at colorful length,

to a reporter from The New York Times.

Or maybe, if we want to be slightly more nuanced about it, do not

lightly take on high-profile commissions at deeply fraught sites of

spectacular terrorist violence that are run by opaque and multilayered

bureaucracies—especially at a time when the media is ready to take

scalps in its quest to expose the excesses, architectural and otherwise,

of the pre-crash boom years. Do not, in other words, produce buildings

that turn you into a tantalizingly convenient straw man.

The IST is a 162,000-square-foot, oval-shaped, two-story building that

cost $60 million to put up. (That’s 1.5 percent of the Ground Zero hub’s

estimated final tab.) It holds offices for faculty and the university’s

president as well as classroom space and a library that has already

attracted headlines for not including a single printed book. Though the

first stories about Calatrava’s hiring, in 2009, mentioned a 2012 target

date and budget of $45 million, university officials say the building

did meet more recent timelines and cost projections.

Early photographs released over the summer certainly made clear that

Calatrava has given Florida Polytechnic the kind of architectural symbol

that it can put on coffee mugs and the brochures it mails to high

school students and their parents. And the school’s PR staff has done

its best to get out in front of any stories about Calatrava’s fee,

freely letting reporters know that his firm earned $13 million for the

project. To what extent the Lakeland building will do the more

complicated work of recalibrating Calatrava’s place in the profession is

a tougher question to answer, and one that I’d flown to Florida to try

to answer.

The brand-new campus of Florida Polytechnic University, created by an

act of the state legislature, sits in what was very recently farmland

about 50 miles southwest of Orlando. (When I asked my university tour

guide what used to occupy the site, she had a one-word answer: “Cows.”)

But this is hardly a remote part of the world—or one untouched by the

work of prominent architects. Florida’s Interstate 4 runs right along

the northeastern edge of the campus. Florida Southern College,

which includes 18 buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright, is 13 miles away,

and Celebration, Disney’s new town featuring a post office by Michael

Graves, FAIA, and a bank by Robert Venturi, FAIA, and Denise Scott

Brown, is reachable by car in about 35 minutes, as is Disney World.

Still, when Calatrava was hired to design a master plan and the IST

building, he was handed a blank slate. That is the first clue that this

foray into American architecture was perhaps destined from the start to

work out better than Calatrava’s star-crossed effort at the World Trade

Center site—or for that matter in Wisconsin, where his 2001 Milwaukee Art Museum addition,

complete with giant movable brise-soleil and stretching between the

original building and Lake Michigan, was initially praised by many

critics before drawing fire as an example of wasteful spending.

Simply put, Calatrava, even more than most architects, works best when

he has both political and architectural elbow room. In Florida, he was

given space to operate and a healthy, though not extravagant, budget.

For an architect up to his neck in bad press, it is hard to imagine a

more useful or timely combination. At the same time, Calatrava has no

excuses in this case, with a generous site and clients who were

pleased—thrilled!—to have him.

In fact, the final product, produced in collaboration with local firm

Alfonso Architects and built of reinforced concrete, strikes me as an

example of Calatrava’s architectural approach and creative sensibility

distilled, for better and worse, to its essence. There are all the usual

influences on view—the Eero Saarinen forms rendered in the Richard

Meier, FAIA, palette—and they are remarkably legible and easy to parse

here, since they are laid out on a flat, unsullied, Oscar Niemeyer–Lucio

Costa site and complemented by those ponds, which Calatrava arranged to

navigate a subtle descent from south to north. The landscape barely

mitigates the punishing Florida sun; it is, more than anything, a frame

that provides dramatic and flattering views of the new building. In

time, as other buildings fill in what is now empty space—there is a

workmanlike (and white) dormitory and a small student services center

about 100 yards south, but nothing else—the Calatrava design will have

to deal with a bit more context.

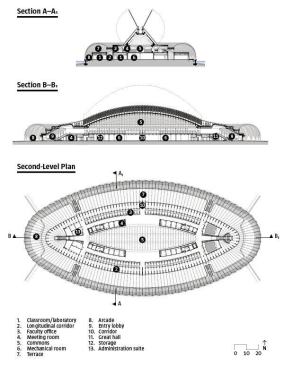

In plan, the building is straightforward and elegant. Two double-loaded

corridors lined in polished concrete, one at ground level and another

on the second floor, curve in a gentle oval arc around the building. The

lower one opens onto classrooms on its outer edge and to studio space,

labs, and an auditorium in the center of the building. Upstairs, the

corridor has faculty and administrative offices on the outside and, to

the inside, some small conference and study rooms as well as the

building’s functional and architectural heart: a multipurpose library

and study space with a soaring ceiling that is known as “the Commons.”

Two grand staircases, one on each end of the oval, lead to the upper

floor.

The skylight above the Commons is shaded by a complex system of

aluminum louvers that can be raised or lowered depending on the

intensity and position of the sun; on the day I visited, all 94 louvers

were down, casting a series of geometric shadows onto the floor but

giving the room plenty of natural light.

This roof system—at 250 feet, twice as long as the one at the Milwaukee

Art Museum—is perhaps the closest thing the building has to a statement

of principles. Given the recent criticism Calatrava has faced, it is

something of a defiant one. My buildings will still take on anthropomorphic form, this project says, and they will still be movable and bone-white and instantly recognizable as my work.

Of more interest to me was the room beneath that roof, which is among

the calmest and most assured that Calatrava has ever designed, even if

Florida Polytechnic made the odd decision to fill its library, near the

north end of the space, with zero actual books. Instead, students will

be directed to e-books and other digital resources.

The exterior of the building is ringed by pergolas, covering and

lightly shading an upper terrace and a wide walkway at ground level. The

pergolas provide a delicacy that is lacking in some of his other work,

in Valencia and at Ground Zero. Here the effect is less skeletal and

more filigreed.

There are sure to be some complaints from faculty about the almost

punitively small size of their offices, and the fact that those offices

lack ceilings, so that conversations drift easily from one to the next.

And who knows what surprises the operation of the roof system has in

store. In general, though, the allocation of space, resources, and even

architectural attention is weighted encouragingly toward the students

and the spaces where they will spend the most time.

All of which leaves the lingering question: What will this building

mean for Calatrava’s place among the leading architects in the world and

for his reputation with critics? Assuming the system of louvers doesn’t

turn balky, probably not a huge amount either way. The IST will buy him

a bit of time and good will, but it doesn’t suggest anything resembling

a reckoning or major philosophical shift.

The building is full of handsome and even some very impressive spaces,

but none of the singularly breathtaking ones that have made Calatrava,

despite his price tag, so attractive to clients looking for marketing

splash to go with their museum wing or train station. It reflects

serious attention to detail and the bottom line; this is the work of an

architect actively trying to prove, or at least re-emphasize, his bona

fides.

If that seems odd for a figure of Calatrava’s stature, it is also a

sign of the post-boom era in architecture and city-making. The object

building, the gleaming icon designed as much for a photo spread as for

its users, is something we now distrust almost reflexively. This is

especially the case when it occupies a former greenfield location most

easily reached by private car, as this one most certainly does.

The size of the hill that Calatrava has to climb to regain the perch he

once enjoyed is not entirely his fault; his buildings have had their

problems, aesthetically and practically, but he has also been made one

of the poster children for boom-time excesses that in the end had more

to do with economics than with architecture.

That hill is dauntingly large nonetheless. The results in Florida, more

about damage control than image overhaul, are at least a step back

toward the top. They don’t play to Calatrava’s harshest critics or

suggest a bombastic architect unwilling to learn from earlier missteps.

They don’t feed the alligators. —Christopher Hawthorne