Project Description

In the early 19th century, when the architect Félix Duban undertook to

transform Paris’s hallowed École des Beaux-Arts, his signal maneuver was

to place a late-medieval archway in the forecourt of the design

academy’s classical piazza. But the Arc de Gaillon wasn’t just

decoration: It was a radical teaching tool, one that demonstrated

through its hybrid Gothic–Renaissance style how structure and form could

evolve over time, and that there was more to architecture than

Greco-Roman antiquity.

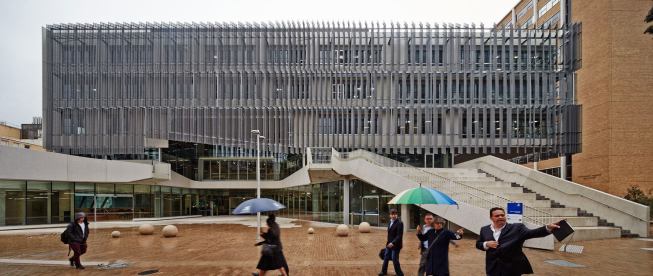

Nearly 200 years later and some 10,000 miles away, two very different firms—Boston’s NADAAA and local firm John Wardle Architects (JWA)—have just finished a new architecture school, the University of Melbourne School of Design’s

Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning building. Located in

Australia’s sunny second city, it’s a building that doesn’t appear, at

first, to incite much intellectual curiosity: Clad on three sides in

perforated aluminum sunshades, with a blank south front, it seems just

another architectural curio on a campus already littered with evidence

of every design trend of the last century-and-change.

But on closer inspection, this is a building whose didactic ambitions

make Duban’s look like a remedial course. Tom Kvan is the dean of the

Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning, and he describes the

four big-ticket items that comprised the original brief: “The building

had to be an investigation into the future of studio; into the future of

academic work; it needed to be a living building; and it had to be a

pedagogical building—one that teaches us and that we learn from

constantly,” he says. On all points, but most especially on the last,

the Wardle–NADAAA team have carried the day with a solution that almost

overflows with ideas—a place the School of Design’s more than 3,000

students will not only learn in but learn from.

The collaboration came about rather serendipitously. “We were contacted

first by John about three days before the competition deadline,”

recalls Nader Tehrani, the now-outgoing head of the architecture program

at MIT and the founding principal of NADAAA. Tehrani had recently

visited Melbourne, but “we hadn’t known it,” says John Wardle, principal

of Collingwood, Australia–based John Wardle Architects, who’d been out

of town at the time. As luck would have it, Tehrani had seen a Wardle

project during his stay, and was sufficiently impressed to join forces

almost instantly. “Nader said yes within about 20 seconds of me asking,”

Wardle says, and in short order the team found out that their proposal

had made it past the first round of the design competition, which

included more than 130 applicants.

Significant changes had to be made to their winning design to fit a

tight university budget, but the core conceit of the design remains

largely unchanged. “The building as a type is very simple,” Tehrani

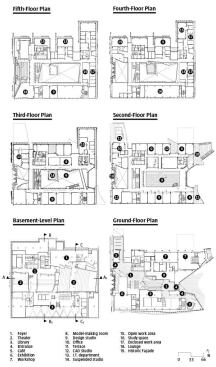

says. “It’s an atrium building, a donut.” It’s a donut with a

difference, however, as this one is lofted up a story: The first-floor

entry level is a continuation of the campus, with fabrication workshops,

the library, and exhibition spaces arrayed around a central concourse;

only on ascending the stairs does the visitor find the atrium, with four

stories of galleries ringed around an open lounge space topped by a

dramatic coffered wood ceiling.

The list of design details, and of the programmatic significance of

each, is fairly astonishing, a result of a Skype-based collaboration

that Wardle describes as “a conversation that constantly generated

ideas.” The undersides of several staircases, for example, are

unfinished, exposing the steel to “reveal how the stair is constructed,”

as dean Kvan puts it. In the entryway concourse, there’s a small glass

portal in the ceiling so that non-architecture students passing from

east to west can get a glimpse into the light-filled atrium above, a

little teaser to encourage them to head upstairs and see what the

designers are up to. From the metal protective mesh surrounding the

galleries to the worktables embedded partially in it to help hold the

screen in tension; from the swiveling panel walls of the atrium-level

studios to the glass windows near the basement auditoriums that give

students a glimpse into the boiler rooms—almost nothing in the building

is without some educational import concerning materials, building

science, and the art of architecture.

All of these little Arc de Gaillon moments inside are set off by one

big one on the exterior. What had been the decorative façade of the

Joseph Reed–designed Bank of New South Wales, completed in 1859 and

gifted to the school after the original building’s demolition in 1932,

has been tacked onto a portion of the new architecture building just as

it had been to the school’s now-demolished previous structure. This

extraordinary set piece and beloved campus fixture (which is secreted

under green scaffolding, and will be until its installation on the new

structure is completed in December) is given an appealing bit of

deference by the brash metal building that surrounds it, with the

irregular zinc louvers billowing around it slightly—“like a curtain,”

says JWA principal Stefan Mee—a lesson in how even the past can find a

place in the architecture of the future.

So profuse, in fact, is the structure’s built-in curriculum that it

leaves one a little in doubt as to how much its already-harried students

will be able to absorb. “The more we got into it, the more scripting we

felt was required,” Wardle says, and the result is a building with a

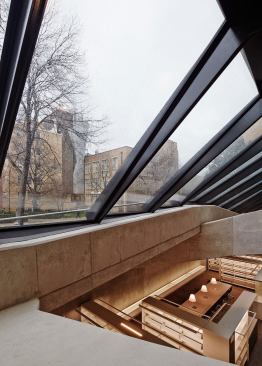

very thick plot indeed. What is likely to become its most recognizable

feature, the striking Suspended Studio that dangles like a wooden

lightning bolt in the atrium, is also a sort of metonym, a symbol of the

whole—a place where the building, and the students in it, seem to be

flying beyond the limits of the possible. That, claims Tehrani, is the

whole point, a mark of how much the necessity of dynamism and

adaptability has become the hallmark of architectural education since

the days of the Beaux-Arts. “We’re still always working with an

understanding that the building has to be timeless,” he says. “But

architecture is changing radically.” —Ian Volner